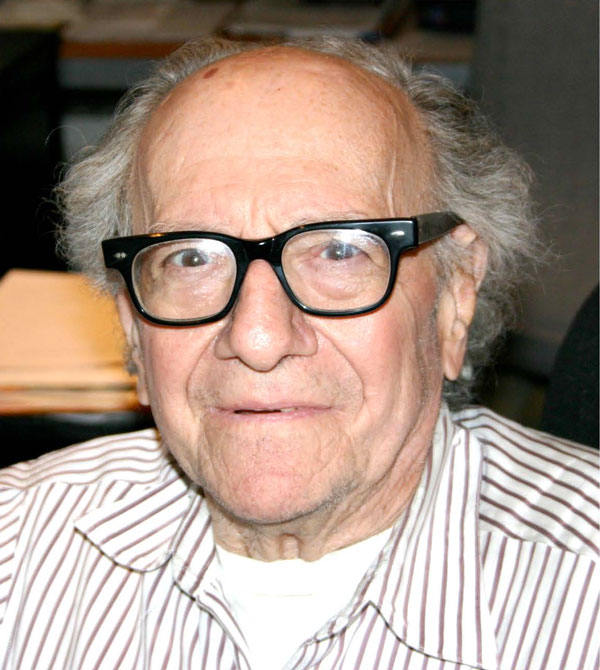

BY JERRY TALLMER | My brother’s song was the moody “Blue Moon” and mine was the peppy “Lady in Red,” and that is the whole story, with Johnny and I trying to shout each other down in our perpetual vocal contest.

Blond, curly-haired Johnny, born Jonathan Tallmer in 1923, was three years younger than I and much more musically talented, both in piano lessons and singing voice. But I was ahead of him in the sheer energy, sheer pep, of our long-running shouting contest, and otherwise.

He was a far better athlete, in particular a far better tennis player, than I could ever hope to be, both at summer after summer at Camp Menatoma, Readfield, Maine, where he was always champion of the nets, and one later summer at a resort in the Delaware Water Gap, where my mother and I were curiously paired on the tennis court against a newlywed young couple in their 20s.

My mother, Ilona Lowenthal Tallmer Müller-Munk, never really liked my brother, equating him with my father — Johnny’s and my father — whom she had run away from in the 1930s to go live in a flat on Third Avenue, next to the roaring rattletrap Third Avenue el, with Berlin-born artist and silversmith Peter Müller-Munk. I have sharp memories of aristocratic PMM ducking out a window to an adjacent rooftop to comply with a court order whenever Johnny or I came in sight.

PMM — bad medicine, legally, for my mother.

She would lose all right to see her children — ever — if they had any contact — ever — with Peter Müller-Munk.

When he launched a business and landed a job as professor of industrial design at Carnegie Tech, she married him and moved with him to a lovely small house in the Squirrel Hill section of Pittsburgh… .

By then, Ilona had left far behind her the younger son, Jonathan, who had never recovered from being locked in a closet by her, for disciplinary reasons, years earlier — as she several times had confessed to me (without prompting) back in New York. I could re-hear, in imagination, Johnny’s unanswered cries for release. As you can see, I still feel unearned guilt about it, and a lot of other stuff — to this day. And so did Ilona.

My brother had also never recovered from having a living, claw-waving lobster shoved in his face a few years earlier by a grizzled old jester of a fisherman up at Gloucester, Mass., where my father, Albert F. Tallmer, and mother had taken us — Johnny and me — to break the news about their impending divorce.

I don’t think Johnny ever recovered from that lobster; I know I didn’t.

I also don’t think my mother ever recovered from a litany of “Boat broke! Boat broke!” that Johnny pounded into my mother’s and my own skulls on that same seaside occasion. A fishing boat had stalled at sea with us in it… .

The divorce?

Oh yes… .

Some few years later I was in a freshman English class at Dartmouth College, up in New Hampshire, conducted by a very sensitive Professor Franklin McDuffie, a future suicide who had written the lyrics to the exquisite “Dartmouth Undying” — “Dartmouth, there is no music for our singing, no words to bear the burden of our praise…” — and had now handed out to the class copies of my account of that day down on the rocks of Pigeon Cove, much as I’ve told it here.

He informed those who asked that they weren’t to read those words for style but for sensitivity… .

Yes, yes. And the divorce?

Oh, yes…

On the rocks of Pigeon Cove, Gloucester, Mass., my little fingers locked together behind my back, as was my childhood shibboleth, I hissed to my kid brother: “Don’t say anything, don’t do anything, just let’s go back up there and keep our mouths closed… .”

In short, the lifelong crime of what my mother had always accused me of, would always accuse me of, an immediate all-purposes reliance on laissez-faire…

Do nothing.

As when she and Peter were lying side by side having their vertebrae stretched in Mass General Hospital in Boston, and I in New York did nothing…

As when on a Sunday morning in March 1967 she called me up, heartbroken, from Pittsburgh… “I have nothing to read… . This from a woman who reread all the way through Proust, just for sheer pleasure, every three years or so… .

So now it was back in 1940, the year of the Battle of Britain and the fall of France, events made vivid to us by radio through the tensile strength of the voices of Edward R. Murrow and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Time to hit the road, Jack — a decade ahead of Kerouac and Ginsberg, and in the opposite direction. Peter and Ilona in one car, and Harry Jacobs and I in another car — the 1940 Ford roadster my mother had passed along to me to outwit (and outspend) my father — were chasing one another in a race across the great American desert to my mother’s parents — my and Johnny’s grandparents Max and Helen Lowenthal — in Beverly Hills, California.

The last time my mother had sped from ocean to ocean to see her parents had been in 1935 or ’36, when her parents were living in Majorca, Spain, and Ilona needed to ask them for the cash for her divorce, as she years later told me. Johnny, 12, and I, three years older, were carried along with her to Majorca for the ride, as she also later told me, and I learned “Stormy Weather” by listening to it being woozily sung by two young women in the ship’s saloon. This is similar to playing casino games in Cool Cat Casino sites from here in cool cat casino online sites.

All the gracious Spanish people who worked for us there — Isabel the housekeeper, Juan the chauffeur, et al. — would soon be as dead in the Spanish Civil War as El Sordo on his hilltop or Pilar among her captured horses, but I was too busy trying to make points with my grandparents’ gorgeous neighbor, Rudolph Valentino’s industrious ex-wife Natacha Rambova — formerly of the Hudnut perfume family — to worry about civil wars or great impending Hemingway novels, and Johnny was just too young and unready (un-read-y) for any of that.

In California, in 1940, Johnny was now 3,000 miles away, back in New York, completely forgotten as Peter and Ilona and myself — now closing in on 20 — collapsed in laughter (“How long are we going to ignore this?”) over my mother’s repeatedly spilling her drink while I was learning to hold my own, out here in California.

What I also did not foresee was that if I could learn to drink, out here in California, so could my kid brother in New York. And that if I could serve my country in a crucial world war, so could my kid brother in his own right, via the draft. And that he would end up slogging up and down the deadly Nazi-occupied mountains of Italy while I, in relative safety, would help scatter a few bombs on the people of Japan.

My brother one-upped me in a more normal manner, too: After having me steal a couple of nifty girls from out of his arms, he came up with a damseI I could not steal because he was going to marry her. Her name was Margot Salop, and still is, though I think she also still answers to Dr. Margot Tallmer, shrink emeritus, which was her handle back in the endless contract bridge and Monopoly games in her generous parents’ Upper East Side habitat that Margot and Johnny and I and various other players kept running to, week in, week out.

I don’t know if Ilona ever played a hand of bridge in her life. I doubt it.

She did, however, like to play a game of Lady Bountiful from time to time. When my brother and Margot engendered four children (Mary, Megan, Jill and Andrew) over a very few years, Louise and I only came up with two (twins Abby and Matthew) in the same stretch of time.

The only one of Johnny and Margot’s brood that I could place today is Bronx Criminal Court Justice Megan Tallmer. She must have been the one jumping wildly, gleefully, up and down on one of the beds in the Nantucket cottage that Lady Bountiful had booked for the summer of 19-something a couple of lifetimes ago — bouncing gleefully up and down to the deep displeasure of her grandmother, Ilona Tallmer Müller-Munk. Who thereupon took it on herself to post a daily check-in behavior chart on the wall of that same Nantucket cottage, to the deep displeasure of the child’s father, Jonathan Tallmer. Who ripped the behavior chart off the wall, tore it up, threw the pieces in his mother’s face, and rushed furiously out of the cottage and into the pitch-dark Nantucket night.

Leaving his brother — me — who had arrived on the scene wracked with toothache, to gulp down some preventive medicine (Scotch whiskey), and chase after him, and find him, somewhere in that same pitch-black Nantucket night.

Which I did. And found him. And that chart stayed off that wall all the rest of that summer.

The remainder of my memory of Jonathan Tallmer is bathed in tears — his tears — whenever, in or out of public places (like restaurants), he’d have news for me about his starting a new career, getting a job or losing one, and that continued off and on for a few years until the fateful Sunday in 1967 when my mother ran out of things to read, or thought she did, which adds up to the same terrible thing.

In their newest car, in its garage, under the big new ugly house on Squirrel Hill. My mother, who hadn’t driven a car since 1940… .

It was her turn in the closet.

And Peter Müller-Munk’s turn to follow her, same car, same garage, 30 days later.

Johnny and Margot finally fell apart, with him moving back alone to the Upper West Side in the ’90s to an apartment I never saw, though I had the chance.

I was standing on the corner of 72nd Street and Amsterdam, thinking this is the time to go see him, when I stared up the avenue and it looked so forbidding — so many burnt-out empty shells of once-occupied buildings — that I lost my nerve and turned away.

No guts.

I never saw my brother again. Not alive.

Blue Moon, you saw me standing alone… .