BY SAM SPOKONY | Having served on the City Council’s Committee on Aging during her first term, Councilmember Margaret Chin was more than happy to take over the committee upon starting her second term in January.

“And I think the senior advocates were happy too,” she said, smiling, during a recent interview in her Council office at 250 Broadway.

Chin, 60, represents the Council’s First District, which covers the Lower Manhattan neighborhoods of Battery Park City, Tribeca, the Financial District, Chinatown and part of Greenwich Village. As chair of the Aging Committee, she now hopes to bring attention and resources to the fast-growing senior population, which (among those aged 60 and above) is projected to reach 1.84 million people — or around 20 percent of the city’s total population — by 2030, according to a February report by the Council of Senior Centers and Services of NYC.

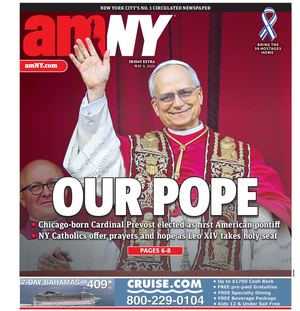

Councilmember Margaret Chin at the Independence Plaza North Senior Center, in Tribeca.

“On any issue that we talk about, whether it’s housing, transportation, health or anything else, seniors need to be at the table,” said Chin. “The effect on seniors has to be heard.”

And she’s hit the ground running, already introducing new legislation and resolutions aimed at protecting elderly tenants from bullying landlords and curbing elder abuse.

Chin’s new bill, introduced on March 12, would double the maximum fine for tenant harassment — refusing to make necessary repairs or accept rent payment, shutting off services like heat and hot water or threatening force — by increasing the penalties from the current range of $1,000 to $5,000 up to $5,000 to $10,000 per dwelling unit.

Since many seniors are long-term residents of rent-regulated apartments — especially Downtown — they are frequent targets of landlords who hope to force them out in order to then sell or lease the units at market rate, the councilmember noted.

The legislation would also create a “blacklist” for offending landlords, by requiring the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development to post information about the violations — including the building address and owner’s name — whenever properties are found to breach city laws against tenant harassment.

“We want to send a strong message that these practices are unacceptable,” said Chin. “We want to protect the residents who helped build up these communities, because they’re the pioneers, the ones who were there 30 or 40 years ago when the market wasn’t that great in certain areas. They’re the ones who invested the time and energy to build up those neighborhoods, to fight for parks and schools, and we can’t let them be forced out now by intimidating landlords.”

The councilmember’s two new Council resolutions, which she also introduced on March 12, would call on the State Legislature to pass laws aimed at stopping financial exploitation and physical abuse of seniors.

One of those resolutions focuses on a bill that has already been introduced in the State Assembly and Senate, which would allow banks to refuse payment from an account when there is reason to believe that the account holder is being exploited through a scam, forgery or identity theft.

Along with the fact that modern technology has increased the danger of scams, Chin stressed that cases of financial abuse against seniors can be difficult to investigate, since victims are often unaware of the exploitation, reluctant to come forward or incapable of giving proper consent to those controlling their finances. In addition, 64 percent of reported perpetrators of financial exploitation of a senior are actually family members, spouses or significant others, according to a 2013 study by the New York State Bureau of Adult Services.

“Financial institutions have a duty to safeguard seniors’ hard-earned savings, and that’s why I’m urging the state to authorize banks to fulfill that responsibility,” said Chin.

The councilmember’s other new resolution calls on the State Legislature to create and pass a law that would require certain professionals to report suspected elder abuse — physical, psychological, sexual or financial — to authorities.

Those falling under that mandate, according to Chin, should include healthcare and social service workers, law enforcement officials, attorneys and investigators at district attorneysʼ offices and financial professionals.

Currently, New York is one of only four states in the nation that do not have such a mandatory reporting law when it comes to suspected elder abuse. And according to a 2011 report by the New York State Office of Children and Family Services, 120,000 seniors in New York City had at that time experienced abuse — but only one out of every 25 cases were officially reported.

“Mandatory reporting will shed much-needed light on a silent epidemic facing older adults in our city,” said Chin.

And with the creation of the city’s Fiscal Year 2015 budget well underway — the final Council vote on the budget will take place in June — Chin is also pushing for increased funding for the city’s Department for the Aging (DFTA), which is recovering from heavy budget cuts that took place under ex-Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration. Bloomberg had reduced DFTA’s budget by $57 million — a whopping 20 percent of its previous total — over the past seven years.

Mayor Bill de Blasio drew cheers from Chin and senior advocates in February, when he pledged to provide $20 million in baseline funding to DFTA as part of his preliminary budget proposal for FY 2015. Many of those advocates were also pleased that, before appointing Donna Corrado his new DFTA commissioner, de Blasio named the Department’s previous commissioner, Lilliam Barrios-Paoli, to be his deputy mayor for health and human services. Along with the fact that Barrios-Paoli has been highly critical of Bloomberg’s cuts, Chin said she believes that having an ex-DTFA boss so close to the mayor will help bring senior-related issues to the forefront of many ongoing discussions.

But the Aging Committee chair is now focused on the budget fight of today — and one of the priorities, she said, will be to push for additional funding for DFTA’s case management program, which provides direct support to homebound seniors.

Currently, each social worker within that program carries a caseload of around 80 seniors, according to the city.

“That’s really a large number, when it comes to effectively doing one-on-one assessments and periodically checking in on the seniors,” said Chin.

So she hopes to secure an additional $3.5 to 5 million for the case management program, which would cut the social workers’ caseload down to around 60 or 65 seniors per worker.

Another key area for Chin, in keeping with some of the action she’s already taken, is to increase funding for education and counseling aimed at preventing elder abuse. The Council has historically set aside around $800,000 each year for that purpose, the councilmember noted.

“But is that enough money to get that program going as effectively as we want it to? No,” she said.

Chin explained that she’ll be pushing for enough funding to replicate some smaller programs that have already started taking place in Brooklyn — involving nonprofit groups working with the Brooklyn District Attorney — which provide cross-cultural outreach on elder abuse in order to bridge the language gap in Chinese- or Spanish-speaking communities. Another $200,000 in funding would allow those programs to be brought to some other communities, she noted, but a much bigger and more ideal increase — another $3 million, based on current estimates — would allow for more comprehensive outreach citywide.

Thinking long term, Chin echoed the sentiments of the new mayor by saying that she plans to push heavily for the preservation and creation of new affordable housing — and in her case, focusing specifically on units for seniors.

There has been much speculation about Mayor de Blasio’s closely guarded — but often referenced — plan to build or preserve 200,000 units, which he has declared he will officially explain in detail on May 1.

Meanwhile, the Council of Senior Centers and Services of NYC (CSCS), a major advocacy group, has already put forth its suggestion for what half of those units should look like.

In its aforementioned housing report released in February, CSCS called on de Blasio to develop or preserve 100,000 units of affordable housing specifically targeted for the growing senior population. Around three-quarters of that could, according to the report, be preserved by reforming the state’s Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE) program, which prevents seniors in rent-stabilized apartments from having to pay periodic increases in their rent.

Currently, seniors are eligible for SCRIE if their annual income is $29,000 or less. CSCS wants to raise that income limit to at least around $36,000 in order to aid tens of thousands of additional seniors in keeping their homes, according to the report.

Chin said during her interview for this article that she wholeheartedly supports that kind of SCRIE reform (although that amending legislation will, like elder abuse reporting laws, have to pass at the state level). But a spokesperson for the councilmember later said that while Chin plans to explore the issue of senior affordable housing further, she won’t able to commit to creating or preserving a specific number (such as 100,000) under assessing needs alongside the Council’s Committee on Housing and Buildings.

However, even though Chin has yet to join in the group’s very specific housing call, she received strong words of support from Bobbie Sackman, the CSCS director of public policy.

“Having been around for the past 25 years, I think Margaret’s going to be a great chair [of the Aging Committee],” said Sackman in a phone interview. “I feel like she has good energy, and is very committed to help seniors take on issues like housing and DFTA funding. And along with the fact that I think she’s going to be very strong on these things, she’s been open to dialogue so far, and I think that’s very important.”