The workers at Cinema Village, one of Manhattan’s oldest movie theaters, unveiled last week that a vast majority of the small staff had signed cards in favor of joining a union.

The 10-person group of workers, driven by a passion for film, say that their desire to unionize goes beyond wanting to improve on the minimum wage income that a majority of them earn. They want to organize in order to have more of a say in how to improve the programming of the movie theater, and make it a more financially successful business.

“We love this theater. We’re invested. We feel like this is our theater. And we want it to run in the best way it can, but the business is hurting right now,” said head projectionist Lee Peterson.

Nine out of 10 the workers at Cinema Village, located at 22 East 12th St., signed cards in favor of joining United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 2179, building off of the union’s successful drives at multiple Alamo Drafthouse branches and Brooklyn’s Nitehawk Prospect Park.

As of publication, Cinema Village’s owner Nicolas Nicolaou had not responded to the workers’ inquiry for voluntary recognition of the union, nor did he respond to a request for comment from amNewYork Metro. If Nicolaou does not willingly recognize this union, the National Labor Relations Board will hold a formal union election that is likely to happen within the next month.

Reasons they’re unionizing

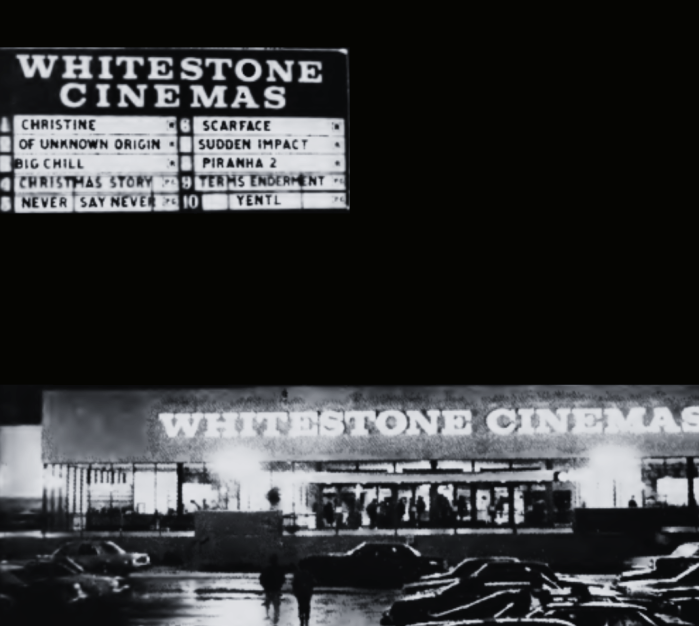

After opening its doors 1963, Cinema Village has remained the oldest continuously running independent movie theater in Greenwich Village. Over the decades, the three-screen theater cultivated a reputation as a hub for independent cinema. It often screens vintage films, cult movies and critical favorites in a format that is increasingly rare among cinemas.

While running projectors, manning the concessions and box office, and operating theater machinery, employees deal with the stress and unpredictability of service work. A majority have been stuck at the legal minimum wage, having never received a raise, and none of the full-time employees receive health benefits.

Peterson, who has been working at the theater for 13 years, said that the moment that catalyzed him into believing that the staff needed a union was when Nicolaou, who had been asked by him and several other workers for raises over the last three years, said such requests were not on the table for the rest of 2024.

Though the cinema hosts a number of progressive film events including the annual Workers Unite! Film Festival, Peterson said that the theater really needs to do better by its employees to earn that reputation.

In fact, the theater makes a sizable chunk of income doing what are called four-wall screen rentals, which entails striking a deal with a film distributor to rent out the space for a week in promotion of an upcoming movie.

The Cinema Village staff, many of whom have arrived as enthusiastic film buffs through the pipeline of NYU and New School film programs, think that the theater could be doing more specialized programming — like director Q&As and small-run showings to attract cinephile filmgoers — that it made its name off of over the years. Many of them including Peterson’s son Jack, who also works at the theater see themselves as stewards of its cultural history.

“It’s the employees that make that history continue. If you care about the plight of the striking actors and writers, you have to care about the people who screen their movies just as much,” Jack said.

Peterson said that he hopes a contract could include language to bolster the theater’s programming and help it survive.

“I do know there are things that we can do, and we — the staff has come up with ideas before, and they’re just always shot down,” he said.