BY OTIS KIDWELL BURGER | Some 50 years ago, my mother, Elizabeth Willcox Kidwell, sold the papers of her grandfather, Sydney Howard Gay, to the Butler Library at Columbia University. The library would not permit me or a niece to see these papers (“too fragile”), and so these letters kept by my abolitionist great-grandfather, including unique records — names, dates, “owners,” money disbursed over two years that aided the escape of more than 200 fugitive slaves — were buried in files for decades.

Then in 2007, a student found them and described them to Eric Foner, a professor at Columbia. And Tom Calarco also heard of the papers and talked about them to his friend, Don Papson, the founder of the North Star Underground Railroad Museum, near Plattsburgh, N.Y.

Foner subsequently published “Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad” (W.W. Norton) this year.

And Papson and Calarco published “Secret Lives of the Underground Railroad in New York City: Sydney Howard Gay, Louis Napoleon and the Record of Fugitives” (McFarland) also this year.

Informing these meticulously researched, illustrated books, this rare material provides an inside look at the brave and dedicated people who worked for the cause of abolition in and around New York from 1833 to ’65.

A recent series on Channel 13 suggested that without the abolitionists, this would have stayed a slave-based country. That seems debatable. Slavery was already stressing the country. Abolition seemed inevitable.

My great-grandfather, Sydney Howard Gay, was born in 1814 in Hingham, Massachusetts, into an old New England family. His father, Ebenezer Gay, was a lawyer, stern and eccentric. Sydney was high-strung and intelligent. His three older brothers had left home. Sydney attended Harvard at the age of 15. Too young. He neglected his studies and was recalled home, sick, two years later. His mother got him a job with a counting house. He lived in Boston with his brother, Dr. Martin Gay, “a distinguished analytical chemist.” Then the company sent him to China. One hundred days by sailing ship, he arrived in Canton just after a devastating fire burned down much of the city and “The Hongs,” the foreign warehouses.

Returning home, he then traveled west, across the Alleghenies, down the Ohio by canal boat, down the Mississippi, where he admired the fine plantations on the banks, and the slaves, so well housed, well dressed, well fed, so much better off than the wretched free blacks in the North. The abolitionists were crazy, and would tear the country apart. But later he wrote in an article about how he was handed a pistol before touring a plantation for inspection. For protection? Against these happy slaves?

Sydney and another young man started a business in New Orleans. It failed. He had to write his father for fare, and arrived in Hingham exhausted, ill and depressed, a failure. He started to read…and emerged sometime later, to his family’s astonishment, a dedicated abolitionist.

He began to teach, write for the Hingham Patriot and lecture, traveling often by horseback. Once, staying at a safe house, he was alerted in the middle of the night; a mob was coming for him. Gay escaped through the back of the house, down a lane into the woods.

He was now to meet other abolitionists, the Hoppers, William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, to go on a speaking tour with Douglass and others, and encountering more stories.

In 1842, George Latimer and his wife Rebecca stowed away on a ship in Virginia. Eight days after arriving in Boston, Latimer was recognized. His master came up from Virginia and had him jailed and charged for larceny. Three hundred black men protested on the courthouse steps, a petition of 65,000 names — weighing 15 pounds — was circulated and George’s freedom was bought for $4,000. Massachusetts passed a law to prevent this from happening again. William Garrison praised God.

Apparently, no one thought it was odd to charge a man with larceny for stealing himself.

In 1845, Jonathan Walker arrived at Sydney Gay’s office at the National Anti-Slavery Standard. He had been a shipwright and had been caught in Florida trying to smuggle seven fugitive slaves from Pensacola to the Bahamas. The seven slaves were returned to their master, with one trying to commit suicide. Walker was jailed for one year, chained with 20-pound chains, barely fed, forced to sleep on the floor…and publicly branded on the palm of his right hand with the letters “SS,” for “slave stealer,” and stood in the stocks and smeared with rotten eggs. But such cruelty was regularly inflicted on slaves — chaining, whipping, branding and degradation sometimes for minor offenses or for running away.

Sometimes valuable “property” was even crippled as punishment or a deterrent to others.

Walker moved to the Midwest and was encouraged to give talks about his ordeal. His branded hand became one of the anti-slavery movement’s most powerful symbols.

Sydney Howard Gay became editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard in 1844. The Standard office was a busy place. Gay edited, wrote, did layout and proofread through long days and nights. He also entertained people like the Hoppers, Wendell Phillips and other abolitionists, meanwhile funneling fugitives on their way north. Fugitives were sent from stations in Philadelphia or Delaware, and were met at the ships or trains by Louis Napoleon, a free black man, who conducted them to the Standard office. This was well known; why didn’t the slave catchers hang around the door, waiting? The whole system was not really “underground” or secret. Once a visiting African was even escorted by a friendly policeman to the Standard office, for safekeeping.

No photographs or pictures of Louis Napoleon have been found, although many newspaper reporters knew him. The secret records from the Butler Library cover the last two years of Gay’s tenure at the Standard: He included names of runaways, owners’ names and the amount of money he disbursed to help 200 slaves on their way to freedom.

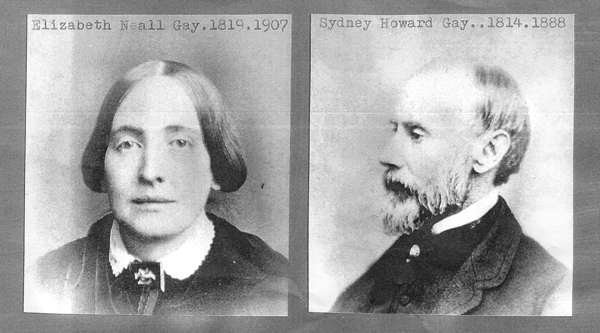

During his earlier years of riding on horseback on lecture tours, Gay met Elizabeth Neall and her abolitionist parents, Daniel Neall and Sarah Mifflin Neall. Sarah’s father, Warner Mifflin, had been one of the first Quakers in this country to unconditionally free his slaves. (They were actually his wife’s slaves, but wives could not own property.) Daniel Neall had once been tarred and feathered by a mob because of his beliefs — out of some respect, not on his bare skin, which could be fatal.

“Ruined a perfectly good jacket,” he said later.

Elizabeth met Gay…mud-spattered and exhausted…on her doorstep. “Fresh and beautiful…his future was decided!” says a family account. Elizabeth was “very well educated for a woman of her day.” She drew well, wrote poetry, was intelligent and a Quaker. She had to leave her Quaker Meeting in order to marry an outsider.

Eventually they settled in a “white carpenter-Gothic house designed by Ranlett” in the northern part of Staten Island, where many abolitionists also lived. Many people came to visit. Gay took the ferry to Manhattan to the Standard office, and later to the New-York Tribune office, where he worked with Horace Greeley.

Slavery had been a part of the Americas since the beginning. Aztecs, Mayans, Incas, etc. had their very own slaves. When Columbus landed in the Bahamas, he eyed the Taino Indians, and said, “a very sweet and hospitable people. They will make good servants.” They didn’t. After they had all died of overwork and unfamiliar diseases, the Spanish replaced them with African slaves, who built them a road across the Isthmus of Panama — 100 years before Plymouth Rock — on which they hauled the gold looted from Peru to the treasure ships at Porto Bello… . So much gold that it depressed the price of gold throughout Europe. Some of the slaves escaped and exacted horrific revenge, pouring molten gold down the greedy throats of their Spanish captives.

The Dutch brought slaves to Manhattan and treated them with greater decency. Later, the English imposed harsh restrictions on African slaves and Native Americans.

During the Revolution, the English recruited black slaves with a promise of freedom. When they lost the war, they shipped several thousand black Americans out of the country; some descendants still live in Nova Scotia today. Washington also enlisted black slaves. (What became of them? Did they get reabsorbed into the South where Washington lived?) Blacks fought on both sides of the Civil War, and many came north when that war ended. Those who stayed in the South suffered another form of slavery after Reconstruction, starving as sharecroppers or being “arrested” when labor was needed and forced to work on chain gangs.

The slave ships — sponsored by many European nations — brought more than 12 million slaves (those who survived the trip) to the Americas. Most were brought by the Portuguese to Brazil, but 388,000 arrived in the American South. They were sold like livestock, teeth and muscles checked, etc., and on the plantations began lives of learned helplessness.

Body servants washed, fed and dressed the white slave owners and their infants. Gangs of slaves worked like machines in the fields. Slaves were kept subjugated by fear and enforced ignorance. It was a crime to teach a slave to read. And yet the slaves, kidnapped from many tribes, and speaking many languages, developed a common language and a common culture, and probably learned a lot about the world just by listening to the dinner table and bedroom conversations of their owners…flies on the walls — “three-fifths human,” yet smart enough to know there was a better way up North.

But the North was not so innocent. Its inhabitants had grown to love slave-raised and -produced sugar, rum and tobacco. And the great mills of England and New England depended on slave-raised cotton. Cotton cloth was sold around the world. The New England coastal towns grew rich on whales and slaves. Many Northerners, therefore, were furious at the anti-slavery activists who threatened their livelihoods. Abolitionists were often violently attacked or even murdered. For their part, some abolitionists refused to use sugar, rum, tobacco or cotton cloth.

The United States banned the slave trade in 1808, but the law was frequently broken. The need for slaves accelerated after the cotton gin was invented.

Children of a slave mother were slaves, regardless of who the father was. Some owners kept the children, but others bred slaves to sell. One man visiting a plantation was startled to realize that many of the field hands were the owner’s own offspring. (A few owners did provide for such children and their mothers, but rape was a cheap way of acquiring new slaves.)

And a boy who might pass for white if he escaped North, was sold deeper South, and put to work in the fields until he became a more “suitable” color.

Some of the fugitives arriving at the Standard office and sent up North were noticeably less dark and African looking.

Handsome Fredrick Douglass was half-white, an escaped slave who taught himself to read and write and became a compelling orator and international figure. To escape recapture after publishing his autobiography, he had to flee to England for safety.

Great Britain ended slavery in her territories in 1834. The Bahamas, Jamaica and Bermuda became free without any serious consequences — which is why Walker was taking slaves to the Bahamas and Douglass fled to England.

But in the U.S., the economies of the South and the North were deeply embedded in slavery. Initially, abolitionists like Garrison, publisher of The Liberator, thought the problem could be solved by moral suasion, logic and reason. Others thought violence was the answer. Violence had already killed a newspaper publisher, and now Nat Turner and John Brown and their followers turned to violence for freedom! And were violently killed. Violence erupted into the Civil War, which killed more than 700,000 people….50,000 at Gettysburg alone.

One hundred years after Reconstruction, civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated…and our country is still not free of its slave history.

Many abolitionists also spoke out for women’s rights. Like slaves, women had very few rights. They had few good ways of earning a living. The charming romances of Jane Austen contained a hard fact: A woman’s life depended almost entirely on choosing and attracting the right husband. In America in the 1800s, if a woman’s husband turned out to be a drunk, a wife beater, a gambler or even a murderer, she had nowhere to turn. Any money she might have had became his. If she left, she would be penniless…and her husband would keep the children.

(California during the Gold Rush was so desperate to attract wives for miners it passed laws to allow married women to keep whatever money they had. It also made itself slave-free despite attempts by Southerners to bring slaves and plantations into the territory.)

Sydney and Elizabeth Gay worked tirelessly for the abolitionist cause, and for women’s rights, too. But it was not until a generation later that their daughter, my grandmother, was able to stand on the back of an open touring car and exhort of “some children, stray dogs, and the town drunk,” until a crowd collected and the main speaker was able to address the subject at hand, “Votes for Women!”

Sydney Howard Gay retired from the National Anti-Slavery Standard after 14 years, sick and exhausted. He later joined the Tribune under Horace Greeley, who promoted him to managing editor. Yet, Gay and Greeley did not agree politically. On the mornings when Sydney’s editorial appeared on the front page, Elizabeth wore her bonnet at a jaunty angle. When Greeley’s appeared, the bonnet almost hid her face.

During the Civil War draft rioters attacked the Tribune office, probably due to Gay’s abolitionist editorials. Greeley, a pacifist, was whisked away to safety and a young reporter sneaked out to Governors Island for guns. But, as the papers noted, the “ammunition doesn’t fit the guns!” Gay was getting ready to use the steam hoses from the steam presses to repel the mob when the Army showed up.

Two other men have quite different accounts of how they brought guns and grenades into the Tribune. In any case, the ammunition did not fit the guns, and the grenades would have blown everyone to hell. But the rioters, hearing of these preparations melted away.

(Similarly, at The New York Times, as Publisher Arthur Sulzberger, Jr. will tell you, during the riots, they installed a Gatling gun in the building’s window on Newspaper Row to defend the pro-Lincoln paper.)

On Staten Island, Elizabeth sent the children to safety and had a reporter teach her how to shoot, and sat up all night with a pistol. “A Quaker! With a gun,” she mourned. But these were violent times.

The rioters did come to Gay’s house, but stopped first at a bar on Bard Avenue, whose bartender — not previously known as friendly to Gay — told the mob the Army was down there waiting for them.

So the mob went back to the Staten Island Ferry and instead kicked an old negro woman apple-seller to death.

Gay and Greeley finally parted company, and Gay retired to Staten Island. He wrote a biography on James Madison and a four-volume history of America with William Cullen Bryant. But Bryant died halfway through the first volume. Gay finished it. I don’t know who got the credit.

His last years were pain-filled and he was partly paralyzed after a fall. Elizabeth lived on to become “a very old lady in white lace cap.”

Most Africans sold to slavers were prisoners, taken in many tribal wars. One chieftain told slavers they were really performing humanitarian service; for what could he do with his prisoners if he couldn’t sell them? Just kill them.

The “peculiar institution” caused hundreds of years of pain, injustice, death and war, only to be followed by lynchings, Jim Crow and, eventually, Selma and civil rights.

This book describes those dark, often-forgotten days when abolitionists, black and white, helped to achieve a second revolution, in which all of us, regardless of race, religion or creed, at last had a real hope of freedom.

Don Papson will speak about “Secret Lives of the Underground Railroad,” and I will share some family lore on Sun., Sept. 20, beginning at 6:30 p.m., at Left Bank Books, 17 Eighth Ave., between 12th and Jane Sts. ($5 suggested donation.)