By Lucas Mann

Talk about active seniors. Last Wednesday, senior citizens from all over New York City converged at City Hall, along with politicians and organizers, to make their voices heard. The gathering followed the announcement by the New York City Housing Authority that it may soon have to face the grim reality of closing its senior centers.

“NYCHA has lost over $611 million in funding due to the ongoing disinvestments in public housing at the federal level,” said Millie Molina, NYCHA’s deputy director of communications, relaying the agency’s statement after the rally. “We receive no funding for community-based programs. Barring new funding to support our unfunded community centers and programs, NYCHA will be forced to imminently take these tough actions.”

The hundreds who gathered on City Hall’s steps on June 11, however, refused to accept the inevitability of those “tough actions” — more precisely, the shutting down of 147 NYCHA senior centers. On the steps of City Hall, in brutal, cloudless noonday heat, protesters held up their signs, desperately urging the city to commit $30 million this year to help these senior centers and Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities, or NORC’s, survive. The city councilmembers who came out to support the seniors’ cause were quick to recognize the dedication of those standing in the pre-summer heat.

“I see seniors here who will take whatever they’ve got — their walkers, their wheelchairs, their pacemakers — to City Hall,” said Councilmember Charles Barron, from Brooklyn. “We are 430,000 strong. If you mess with us, we will shut this city down,” he warned.

Cheers rose up from the crowd on the steps. One white-haired man in the crowd screamed a rapid-fire translation of Barron’s words into Spanish and another cheer rose. The sense of urgency was palpable in the words of every speaker that afternoon.

Councilmember Robert Jackson encouraged continued vigilance from the protesters, assuring them that money for NYCHA was a “top priority” of the Council’s Budget Committee, Council Speaker Christine Quinn and the Council’s Black, Latino and Asian Caucus, of which he is the co-chairperson. “Working together, we can get this done,” Jackson said. “It will be three weeks at the most, but you must keep the pressure on.” The crowd erupted into cheers of “Keep the pressure on,” as Jackson walked away from the podium.

The rally was also used to emphasize the totality of the consequences of the cuts — 147 senior centers, 136 community centers, 10 Naturally Occurring Retirement Community Social Support Programs (NORC S.S.P.’s). Then there is the less-publicized issue of the various community programs that have been able to operate in NYCHA facilities that could now be forced to pay rent and utilities out of their budget range; one hundred seventeen childcare and Head Start programs and 37 after-school programs fall into this category. Thus, the cuts would impact not only seniors, but city youths who participate in childcare and Head Start programs, as well as free after-school programs.

“You are looking at the closing of not only senior centers, but youth programs,” Letitia James, another Brooklyn councilmember, stressed to the crowd. “This affects 7,500 children. The federal government has turned its back on our children, particularly our children of color — children who look like me.”

The people who would be affected by these proposed cuts come from a variety of neighborhoods, in all boroughs. All came together on the City Hall steps, organized in large part by the United Neighborhood Houses, the citywide federation of settlement houses. One neighborhood that was very much present at the rally was the Lower East Side, a neighborhood with many seniors who could be put in jeopardy. As Susan Stamler, director of policy and advocacy for U.N.H., put it, right nowthe Lower East Side is “rich in settlement houses.”

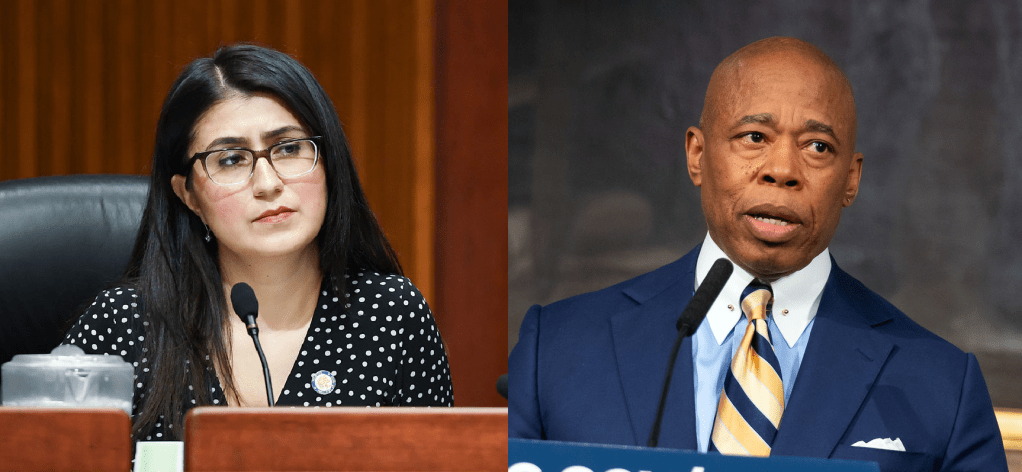

Rosie Mendez, councilmember for Council District 2, which contains the Grand Street Settlement, the Henry Street Settlement, The Meltzer Towers Senior Center and the Baruch Addition Senior Citizen Center, was an active participant at the rally. Mingling with seniors and organizers afterward, Mendez was frank and impassioned speaking about the value of the senior centers in her district.

“I know when I go into one of my senior centers and someone hasn’t come in for a couple of days, someone goes to their apartment to check if they’re O.K.,” Mendez said. “They’ve found people on the floor, hurt, and helped them. If the people from the center hadn’t been there — I mean, God forbid. We need to not just provide affordable housing for seniors, but also give them these social services.”

Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer was not at the rally, although his Brooklyn counterpart, Marty Markowitz, attended, pointing to the elderly people behind him and proclaiming, “You are the best of New York City.” In an e-mail statement from his office, Stringer said that he, too, has been fighting to ensure the preservation of the senior centers; Stringer also included a harsh criticism of NYCHA’s fiscal planning, quite different from the critiques at the rally, which focused more on the city’s responsibility to provide more funding.

“To suggest that community centers and senior centers must be closed in order to preserve public housing is outrageous,” Stringer said. “We predicted two years ago that NYCHA would continue to face operating deficits, but they blindly pushed ahead with plans that would not and could not solve the problem.” He went on to accuse NYCHA of an inability to “manage its finances” and spoke of the need for an “outside party” to check NYCHA’s budgets and try and find solutions that could work to the benefit of residents.

Whoever is to blame, the hundreds of seniors that congregated at City Hall were not going to let their fate be decided by organizations that did not have their best interests in mind.