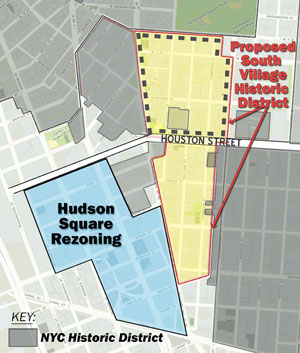

The Landmarks Preservation Commission has pledged, by the end of the year, to consider designating half of the remaining unlandmarked section of the proposed South Village Historic District — specifically, the yellow area north of Houston St.

BY ANDREW BERMAN | On March 20, the City Council voted to approve Trinity Real Estate’s Hudson Square rezoning. This was the third major rezoning in Community Board 2 within a year, following the N.Y.U. 2031 rezoning and the St. Vincent’s/Rudin rezoning. The other two rezonings were far more troubling in terms of their negative impacts and violating fundamental principles of good planning and fairness. The Hudson Square rezoning was nevertheless a mixed bag with some positive changes, but which also failed to address many community concerns and to keep many commitments made by city officials. The rezoning also shed light upon just how much the land-use approval process can be driven by real estate interests rather than the concerns of the most directly affected communities.

The Hudson Square rezoning did have the opportunity to be a win-win. Developers wanted the previous zoning changed because it did not allow highly profitable residential construction, and felt property values would improve and rents would increase if the neighborhood had a larger residential base. The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation and many other groups wanted the allowable size and bulk of new development in Hudson Square to be reduced from the massive proportions that the old zoning allowed. There was a near-universal desire for change, and seemingly that change could have met the needs of all stakeholders. Unfortunately, that’s not quite what happened.

The roots of the Hudson Square rezoning can be traced, in large part, back to the construction of the Trump Soho, the much-maligned “condo-hotel” that threw into sharp relief the flaws in both Hudson Square’s zoning and the manner in which the city chose to interpret that zoning.

In 2007, with the support of City Council Speaker Quinn and Borough President Stringer, the city approved permits for that project’s construction. G.V.S.H.P. and many others objected to the Trump Soho’s height and size, though unfortunately it was undeniable that this scale was allowable under the existing zoning. However, we also argued that as a “condo-hotel,” the Trump Soho violated Hudson Square’s zoning prohibitions on residential and residential-hotel development, and thus should not be allowed to be built. In spite of this, city officials let the project proceed, claiming that ambiguities in the language of the existing zoning prevented them from stopping the development. They did, however, pledge to support changing the zoning to address the concerns raised regarding the Trump Soho development.

For years after this, however, G.V.S.H.P. and other community groups pushed city officials to fulfill this pledge by putting forward zoning changes to appropriately shape development in Hudson Square and ensure that condo-hotels could not be used to circumvent intended zoning restrictions. But the city repeatedly refused to do so.

Instead, years later, the city allowed Trinity Real Estate, a real estate developer that owns a great deal of property in Hudson Square, to put forward a privately initiated rezoning plan. But this plan, as modified and approved by the City Planning Commission and the City Council, did not address many of the concerns community groups had originally raised.

For instance, Hudson Square’s old zoning allowed new development of an extremely high density — the same density allowed in much of Midtown. But the just-approved Hudson Square rezoning still allows the exact same very high density of development.

Hudson Square’s old zoning also had no explicit height limits. At 454 feet, the Trump Soho was far and away the tallest building ever constructed in the area under that zoning, giving a sense, practically speaking, of how tall one might build in Hudson Square under the old zoning.

But rather than prohibiting development of such a scale in the future, the new Hudson Square zoning explicitly allows another development, at Duarte Square, in the southern end of Hudson Square, to rise to virtually the same height as the Trump Soho. And nothing has ever been done, in the Hudson Square rezoning or elsewhere, to address the supposed “loophole” that allows construction of condo-hotels where residences and residential hotels are prohibited.

While failing to address some of Hudson Square’s problems, the rezoning actually exacerbates others. One of the area’s biggest problems is its overwhelming traffic, largely connected to the Holland Tunnel entrances and exits. Yet the Hudson Square rezoning will clearly increase the amount of development in the neighborhood, and thus inevitably increase the already crippling traffic as well.

The new zoning is not without some arguable advantages. But a closer examination of these benefits reveals a more complicated picture.

While the new zoning allows more development than the old zoning, it does place some new restrictions on what form that development may take.

Under the old zoning, hotels were the most common type of new construction in Hudson Square. The new zoning makes hotel development more difficult (though not impossible), and makes residential development much more likely. Additionally, outside of the Duarte Square site, the rezoning does put new height limits in place — 290 feet on wide streets, and between 185 and 230 feet on side streets (depending upon the site, and whether or not affordable housing is included). While in this respect the rezoning may be better than the old zoning, it clearly did not go nearly far enough.

Most Hudson Square buildings currently rise no more than 200 feet, and thus the rezoning encourages more out-of-scale construction. Worse, while Trinity’s original rezoning proposal actually called for lower height limits (in some areas — known as “Subdistrict B” — no more than 125 feet, and no more than 185 feet on side streets), through the approval process, the 125-foot limit was entirely eliminated, and the 185-foot limit was raised on several sites. Trinity’s original proposed height limit for wider streets was lowered from 320 to 290 feet through the approval process, but this decrease is not nearly as great as the aforementioned increases in allowable height that were made through the same process.

The rezoning’s proponents argue that one of its benefits will be to turn Hudson Square into a 24-hour neighborhood, with full-time residents, more foot traffic and a livelier retail mix. Clearly, many local businesses, and some cultural institutions and residents, wanted such a change.

But many others did not. The opponents argued that next-door Soho has more than its share of round-the-clock activity and street life, and that keeping Hudson Square low key and relatively quiet was a good thing. This perspective, while raised frequently at the public hearings, was ignored in the rezoning process, and not reflected in the final results.

The rezoning’s proponents also point to the inclusion of a new school, funding for recreational space, and provisions for the construction of affordable housing as public benefits. But here too a closer examination of these benefits reveals a much more complicated picture.

The Hudson Square rezoning will result in the construction of thousands of units of housing. It will therefore significantly burden the area’s already overcrowded schools and very limited recreation spaces. Thus, the new school and funding for recreation spaces that accompany the rezoning, rather than being a pure benefit to the community, are actually necessary just to offset the significant additional strain upon local infrastructure and decrease in quality of life the rezoning would bring.

The affordable housing benefit is more complicated as well. There are no guarantees about the amount or percentage of affordable housing that the rezoning will create, since none of the affordable housing is mandatory. Rather, the plan provides incentives to private developers to build affordable housing by allowing them to build more luxury housing than they would otherwise be permitted, in exchange for building a small amount of affordable housing.

But let’s assume for the sake of argument that every developer builds the maximum amount of affordable housing incentivized under the rezoning. This will still, at best, result in the construction of at least four units of luxury housing for every one unit of affordable housing. This raises questions as to whether the rezoning actually makes for a community which is more diverse and egalitarian, or less so.

Finally, the Council’s deal to rezone Hudson Square did include a commitment by the Landmarks Preservation Commission to “hear and vote upon” a little more than half of the remaining proposed South Village Historic District — the section north of Houston St. — before this year’s end. This commitment is very important to G.V.S.H.P., and one we and many others fought very hard for. We argued strongly that the rezoning would put greatly increased development pressure on the neighboring, proposed South Village Historic District, and therefore that the rezoning should not be approved unless the city also landmarked the remainder of the South Village, as it promised to consider doing more than four years ago.

This commitment, secured as part of the rezoning deal, is certainly a very significant step forward from where we were, given that the commission was not moving at all on the remainder of the proposed South Village Historic District. And any landmark designation that results from this deal will have important, permanent benefits, helping to protect this area from threats well beyond any increased development pressure from the Hudson Square rezoning.

But it is also important to understand that this landmarking commitment falls well short of what we called for, and still leaves a significant portion of the South Village unprotected, especially from the enormous development pressure the Hudson Square rezoning will bring to bear upon it.

Not included in the deal is any commitment to landmark or even consider the section of the proposed South Village Historic District south of Houston St. Consisting of nearly half the remaining proposed district, this area is exceedingly vulnerable, and has already seen the largest surge in development activity in anticipation of the Hudson Square rezoning. With the failure to include this area in the rezoning deal, we will have to redouble our efforts to find ways to protect and preserve this historic neighborhood before it is irreversibly altered.

But even north of Houston St., the deal is not unqualified good news either. The agreement reached with the Landmarks Preservation Commission does not require landmark designation of this area until the end of the year — nine months after the rezoning has gone into effect. This means developers have nine months to get demolition, alteration or new construction permits from the city — permits which, if not used right away, still remain in effect and can be used after landmark designation is approved. Thus the deal allows plenty of time for continued and future destruction of this area.

G.V.S.H.P. anticipated this situation exactly. We and our allies began calling upon Speaker Quinn to seek landmark designation for the South Village as a condition for approving the Hudson Square rezoning in 2011, as soon as Trinity’s draft rezoning plan was introduced. We hoped that landmark designation would be secured in advance of, or at least concurrently with, the rezoning.

Additionally, while the landmarking deal calls for the South Village’s northern section to be “heard and voted upon” by the end of the year, this does not mean that the entire area will ultimately be landmarked. Though very unlikely, the commission could vote No on the landmark designation.

More realistically, however, the commission could decide to landmark only part of the district that we have proposed for designation. The commission chose to landmark only about 80 percent of the first section of our proposed South Village Historic District in 2010; it landmarked less than 70 percent of our proposed Gansevoort Market Historic District in the Meatpacking District in 2003; and it landmarked only about half the area in the Far West Village we proposed for landmark designation in 2006. So the ultimate breadth and impact of this landmarking commitment is still to be determined.

Things could have been different: A rezoning deal that met all sides’ needs could have been achieved in Hudson Square. This would have included lower height and bulk limits in Hudson Square — to keep new development in context, fulfill promises made after the Trump Soho, and reduce the impact upon traffic and infrastructure. And it would have also included landmark designation of the entire proposed South Village Historic District, in time to protect it from the increased and overwhelming development pressure the Hudson Square rezoning would create.

This would have still allowed the creation of the residential community in Hudson Square sought by the rezoning’s proponents, and still allowed developers to profit handsomely from new, highly lucrative development.

But in the end, it was in fact developers who drove this train, and who emerged from the rezoning much better off than they were under the old zoning. What had been discussed six years ago as a publicly initiated rezoning to address community concerns became a private developer’s rezoning that many people fought long and hard to improve. What could have been a win-win ended up as a great deal for real estate interests, with mixed results for everyone else.

Berman is executive director, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation