Save or sell?

A long battle over the future of a landmarked Upper West Side church reached the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission on Tuesday, as the church’s owners argued they should be allowed to demolish and sell, and advocates said they raised and would pay millions to help preserve it.

Representatives of the congregation, down to roughly a dozen or fewer, are seeking to demolish the nearly 150-year-old West Park Presbyterian Church, at 165 West 86th Street and Amsterdam Ave., 15 years after the Commission granted landmark status.

The Commission at the time called the building, also the site where God’s Love We Deliver launched and Joseph Papp created what became the Public Theater, “one of the best examples of Romanesque revival style religious structures in New York City.”

The church’s owners claimed financial hardship as grounds to demolish the building, while the Center at West Park said it has raised more than $11 million – and could raise more to preserve the structure.

The church signed a contract with developer Alchemy Properties, which would pay more than $30 million to tear down and build condominiums, if landmark status is lifted, allowing demolition.

Advocates at a packed, standing-room-only hearing, with attendees filling seats and standing against the walls, argued in front of 15 commissioners that this was hardship by neglect, while the church said it sought to save the building, but was unable.

“The congregation is going to continue to survive,” Roger Leaf, chair of the West Park Administrative Commission, said regarding a decision that would allow demolition. “They’ll have new space and funding to endow their operations and support hiring a new pastor. They’d be in the same site in a new structure.”

Leaf, a former chair of the Presbytery of New York City’s audit, budget and finance committees, said the church would receive $32 million for a social justice fund, plus $9 million to build a 10,000 square-foot space and that space, close to $50 million in aggregate value.

“The church would have no choice but to sell the building, if this hardship was turned down,” Leaf said. “We would sell it to the highest bidder.”

Leaf said the New York Presbytery includes 88 churches each owned by its congregation. West Park shrank from 250 members in the 1980s to a handful.

“The Presbytery of New York City has no ownership in West Park,” he said of the church where a sidewalk shed went up in 2000. “All Presbyterian churches are owned by their congregations, which are solely responsible for their upkeep.”

The church’s attorneys argued non-religious uses, such as the arts, are not in its core mission, while arts groups said the church has long welcomed the arts and made them part of its mission.

“It is important to remember that this hardship application is not about the availability of affordable space for the arts on the Upper West Side,” said Valerie Campbell, a partner at Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer, representing the church. “There is no reason for the congregation and commission to get sidetracked by unsubstantiated promises.”

Some Upper West Side residents supported the demolition, saying they believe its absence would not be a loss.

“West Park has been part of this neighborhood’s story for well over a century,” Noel Ellison, an Upper West Side resident, said. “It’s always been more than just a building. It’s been a place of care and connection, but the truth is, the building is in serious decline.”

In a Dickensian twist of a tale of two churches with this building as a battleground, advocates painted a very different picture of a church in need of repair, essentially starved of support, despite efforts to pour millions into it.

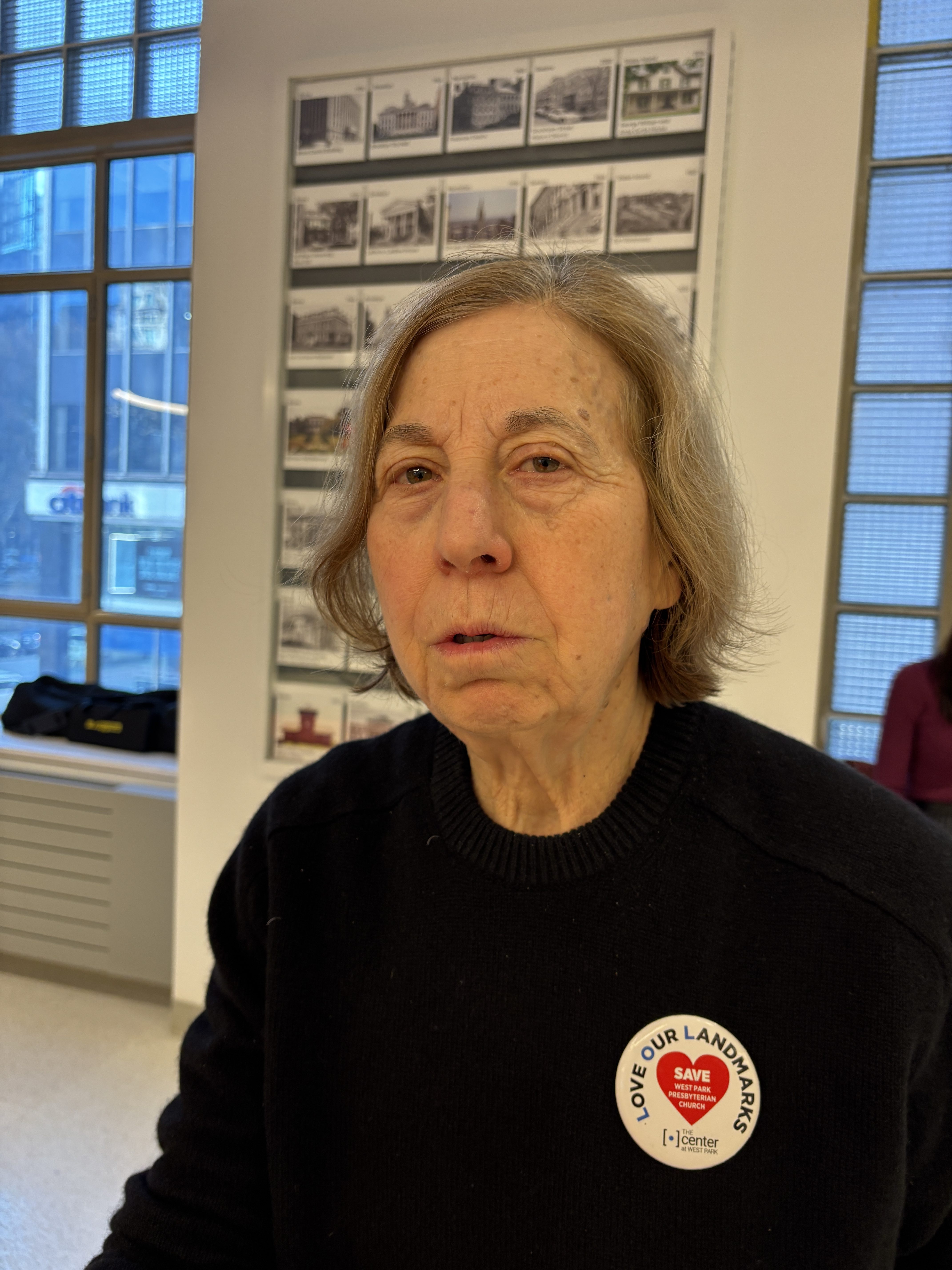

“The key question is whether this building is able to be self-sustaining financially and assume the responsibility or all physical work,” said Center at West Park Executive Director Debby Hirshman of the church where the Lighthouse Chapel Congregation holds Sunday services. “We want to…make this a win-win for all.”

Community Board 7 already opposed demolition, as have State Senator Brady Hoylman-Sigal, New York City Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, and many other officials. The Center at West Park, which the church evicted on July 7, has taken up temporary residency at the St. Paul and St. Andrew United Methodist Church a few blocks away.

“To tear it down would do irreparable harm to the neighborhood and set an irreparable precedent for landmarked buildings,” a spokesman for Congressmember Jerrold Nadler said at the hearing.

The church’s owners pointed to structural and financial studies that, they said, indicated it’s too costly to repair and renovate, while advocates pointed to studies showing lower costs.

“It is an extraordinarily rigorous standard,” Michael Hiller, an attorney representing the Center at West Park, said. “The hardship application is rife with myth.”

To demolish, or not to

While the church said this building is no longer suitable to its mission, advocates said demolition contradicts its mission. “It’s suitable, adequate, appropriate,” Hiller added. “It’s being used as a church and a performing arts facility.”

Advocates said the church wanted to access more than $30 million that Alchemy would provide, while the church said the money could be used to advance its mission and do good.

“Your charge is to do everything to preserve landmarked building in New York City,” said City Council Member Gale Brewer, who helped obtain landmark status, stating the argument that the “cost is so high to repair that church can’t generate a financial return…simply isn’t true.”

“The applicants cannot obtain permission to demolish a church because it has not maintained and repaired it,” Brewer said. “The applicant is trying to create the idea of a hardship when it does not exist.”

Brewer said, “The applicant is trying to hide that the building can be restored for $10 million, not $50 million.”

Actor Mark Ruffalo said the center offered $11 million toward repairs and made a $1.5 million profit last year, entitling the church to $600,000, which the church “walked away from.” “If they say they took that money, they wouldn’t be able to call that hardship,” Ruffalo said.

Paul Camper, an attorney at Hiller PC, said advocates had now raised nearly $12 million toward repairs. “It’s not speculative,” Camper said. “It’s more than enough money to perform the necessary repairs.”

And Jason Zakai, a land use attorney, said the center offered to pay and perform repairs, but was refused. “If there is any hardship at all and we contend there is not one, it is only a self-imposed one,” Zakai said.

Actor Matt Dillon, who has an art studio in the building, said it is ordinary for older buildings to require regular maintenance rather than the wrecking ball. “Old buildings need repair and maintenance, which is completely normal,” Dillon said.

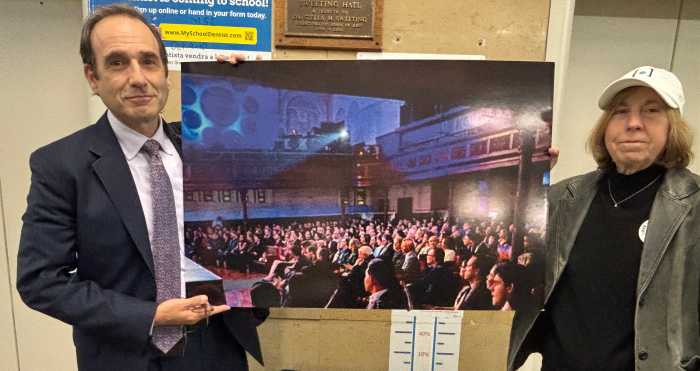

Former Landmarks Preservation Commissioner Roberta Brandes Gratz said once the efforts to demolish cease, it could be easier to raise funds.

“Raising the money to restore West Park is a piece of cake as soon as its future is restored,” she said. “If you approve this fraudulent claim, you will not only set a future for future fraudulent claims. You will cause the worst breach of the landmark law in its 65-year history.”

Others noted the fact that insurers are comfortable insuring the building is a vote of confidence for safety.

“I own a building. I only get insurance when a building is in good shape. This building has insurance,” Brewer added. “How would an insurance company allow the building to be insured if the building wasn’t in good shape?”

Natasha Griffith, a member of the West Park Board, said they made offers to pay for repairs. “Our money is green and spends like everybody else’s,” she said. “Something is not right.”

And playwright Kenneth Lonergan said if owners decide they no longer want the building, that shouldn’t justify its demolition, noting this is about spirit, but also a structure.

“We are here to take care of the building with the congregation, to take it off the congregation’s hands (if they want),” he said. “If you own a Van Gogh and no longer care for it, you do not rip it to pieces and sell the frame.”

Use it, don’t lose it

Brewer noted that the building remains widely used by the public, including the congregation. “Thousands of people go through the building,” Brewer said. “Audience members, people performing, people playing games and worshippers.”

Since 2018, over 60,000 audience members have attended events at the church, including over 25,000 since 2025.

While the church said the building is unsafe, a row of supporters stood with photos showing numerous recent events held in the church, citing children’s ballet, religious services, pickleball games, and more.

“Three days ago on Saturday, the applicant hosted an art exhibition at the church,” Hiller said. “They invited members of the public to come into the building and look at art. They know it is actually much safer than they want to let on.”

Andrea Goldwyn, director of public policy for the New York Landmarks Conservancy, said the “church continues to host public events, music, arts festivals, thrift sales and a weekly open mic night” as well as a church.

Violations and Viewpoints

Church representatives said the building received building violations, while advocates said if every building with violations were torn down, few would remain.

“Every building has DOB (Department of Buildings) violations,” Brewer said. “My building has DOB violations. That should not be of concern.”

Hiller said officials found “longstanding issues” but concluded recent “DOB violations do not appear to be any different than previous violations.” Conditions had not worsened, so they decided there was no need to cite the owner.

“All we need is permission to repair the building, and it is repaired,” Hiller continued. “But they wouldn’t let us do it.”

Zakai said the applicant called the Department of Buildings, asking them to shut down the building. “The DOB did not issue a vacate order,” Zakai said. “The DOB has issued violations. Violations do not mean a building is inadequate or unsuitable for use.”

Air Rights and Hot Air

Advocates argued the church made no effort to sell air rights, which also would contradict financial hardship claims.

“They didn’t ask a single person,” Hiller said, noting a broker they engaged indicated its air rights are worth millions. “We actually did.”

To obtain hardship approval, the applicant must show that the sale of a landmark is contingent on granting hardship. Hiller said the contract with Alchemy indicates the prospective buyer retains the right to buy, even with denial.

“It is not contingent on hardship,” Hiller said, although a particular offer may be. “The applicants’ purchaser can buy the building even if you don’t grant a hardship.”

Others noted the church’s owners opposed efforts to add the building to a national list of landmarks, which could generate grants.

“The atmosphere and character of the church are very inspiring,” Dillon said. “It’s not in the best interest of the city to tear down its history.”

Partnership path

Some suggested the Center at West Park and the church could work together, saving the building, if demolition is denied.

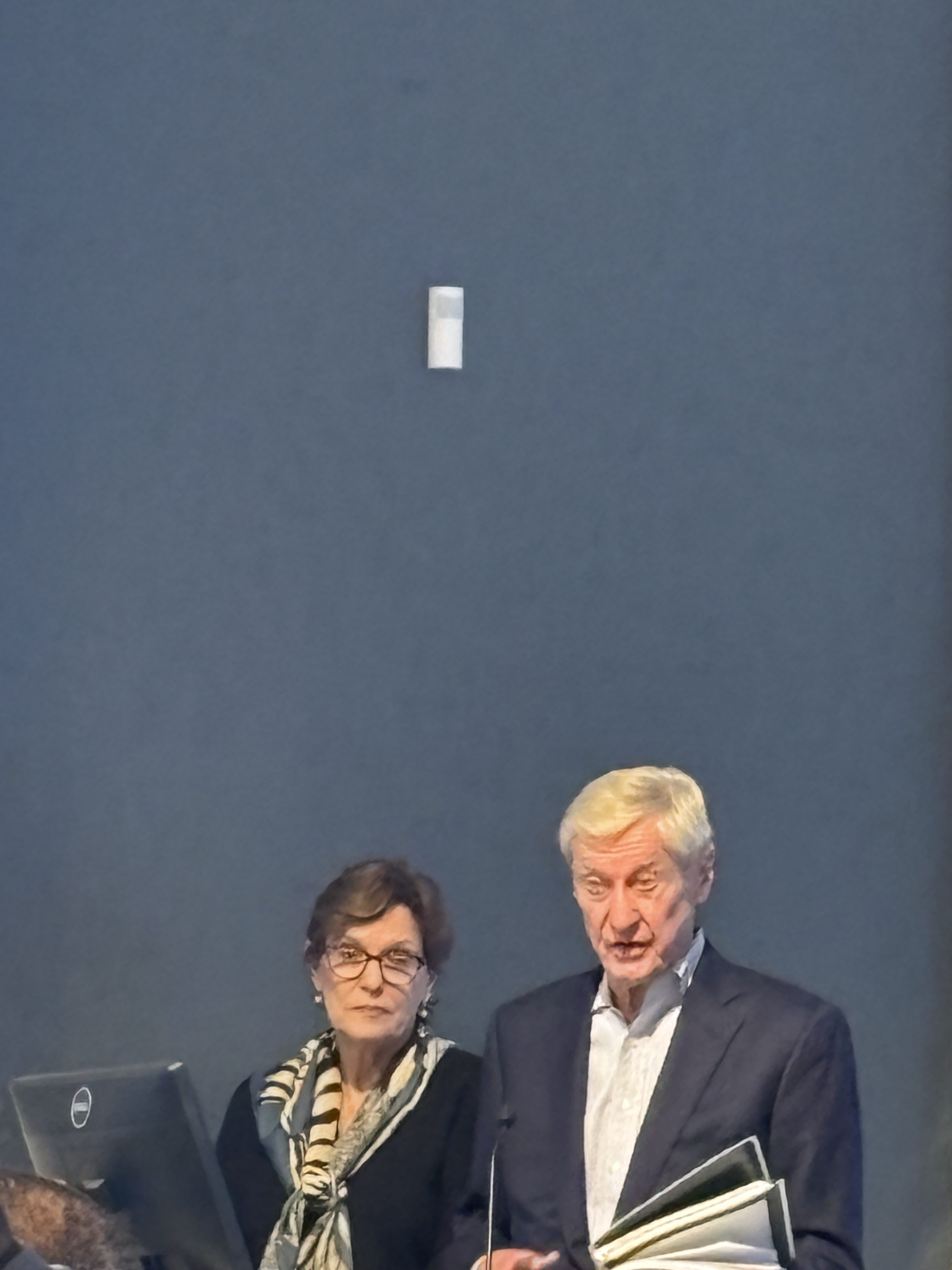

“Stop this contentious and costly battle. Find the public will,” said Ted Berger, executive director emeritus of the New York Foundation for the Arts. “Bring leadership together and philanthropy and public resources.”

Leaf said the church has no desire to rent to the Center, but would sell to the highest bidder. And the church argued the Center for years had not provided much funding to support maintenance.

“We should have raised money in the past,” Brewer said. “There’s a lot of money in the bank.”

Attorneys for the Center noted hundreds of support saving, including numerous prominent politicians and preservation groups.

“Not a single preservation organization, not a single public official… is supporting this application,” Michael Hiller said. “The only people supporting this application are the people associated with the applicant.”

Funding the future

Leaf said money toward a social justice fund would be the biggest donation the Presbytery ever received and a fitting legacy.

“That means the spirit of West Park, its historic mission of passion and service, can live on not just on the Upper West Side, but across New York City,” Ellison agreed.

Campbell said the fund would do good, even if it meant the destruction of the building. “West Park is a nearly 150-year-old church,” Campbell said. “The West Park Social Justice Fund that would be endowed from the sale would benefit thousands of New Yorkers.”

Leaf said new construction would include a space for the community and the church, while denying the right to demolish could benefit nobody. Images showing the center were marked “draft,” which could indicate they are preliminary, sources said.

“To turn the hardship down would not guarantee the building would be preserved,” Leaf said. “It would result in the demise of one of the oldest congregations on the Upper West Side.”

Lower East Side Preservation Initiative Board Member Helena Andreyko said “maximizing return on investment under the guise of hardship” would “set a terrible precedent” and “endanger landmarked religious and other structures.”

There have been only 19 such hardship applications since 2009, with almost none granted, although the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2008 approved St. Vincent’s demolition.

The Commission now considers, and could hold additional hearings, before putting the decision to a vote.

“There could be a precedent that as soon as we neglect our building, we can apply for hardship,” Madelyn Paquette, resident producer, said. “The moment they approve one of these, there will be 100 more.”

Frampton Tolbert, Executive Director of the Historic Districts Council, said the building “deserves a thorough, good faith exploration of alternatives to demolition.”

“The loss of West Park Presbyterian Church would set a precedent that encourages demolition over restoration citywide,” Tolbert said.