BY STEPHANIE BUHMANN | Lorrie Goulet’s New York studio, located in a townhouse in the heart of Chelsea, includes a stunning collection of work spanning seven decades. Set up on pedestals, her many sculptures tell of a life devoted to art. “I was always happy to be in the studio,” she explained, clarifying that it was, and remains, her “favorite place.” In conversation it became increasingly clear that to her, happiness was indeed always rooted in having enough time to work and in maintaining the considerable physical strength needed to tackle her challenging materials — “any kind of stone I could get my hands on,” she explained.

Though her oeuvre also entails painting, drawing and poetry, Goulet is primarily known as a sculptor, who carved each of her works directly by hand.

Born in 1925 in Riverdale, New York, Goulet knew she was an artist early on. Considering that her formative years occurred during a time when women were discouraged from pursuing any profession, let alone art, and when the handful of working female artists could never dream of receiving the same recognition as their male peers, Goulet’s success seems both staggering and inspiring. She did get married (to another artist), raised a daughter, and taught hundreds of art students — but she also, as she proudly noted, created more than 500 sculptures by hand.

Goulet’s story is one of unwavering determination. “I wasn’t interested in any of the things traditionally expected of women like getting married and having several children,” she said. Bolstered by this conviction, she managed to find her unique path, as well as a professional support system. In 1932, at the age of seven, she met Aimee Le Prince Voorhees at The Inwood Pottery Studio, which Voorhees had founded with her husband Harry. There, in the pastoral setting of Inwood Hill without any modern conveniences, Goulet studied with Voorhees for four crucial years, reflecting once that “It was one of my happiest experiences,” and that she had “never forgotten [her] first teacher.” Even when The Pottery Studio was forced to close by Mayor LaGuardia (protested in the press by the then-11-year-old Goulet) and her family moved to Los Angeles, Goulet still managed to find a way to supplement her regular schooling with a serious art education.

In 1940, she apprenticed with local ceramicist Jean Rose. However, it was not until 1943 that Goulet entered art school full time, enrolling at the venerated Black Mountain College in North Carolina. There, she was able to study painting and drawing with Josef Albers, as well as weaving (with Albers’ wife, Annie). It was at Black Mountain that Goulet also met her future husband, the established sculptor José de Creeft, four decades her senior. A visiting instructor at the time, de Creeft is perhaps best known for his 16-foot “Alice In Wonderland” bronze sculpture in Central Park. The couple was married in the fall of 1944. Two years later, they acquired a farm in Hoosick Falls, New York. Through 1968, they worked part of each year there while raising their daughter, Donna Maria de Creeft.

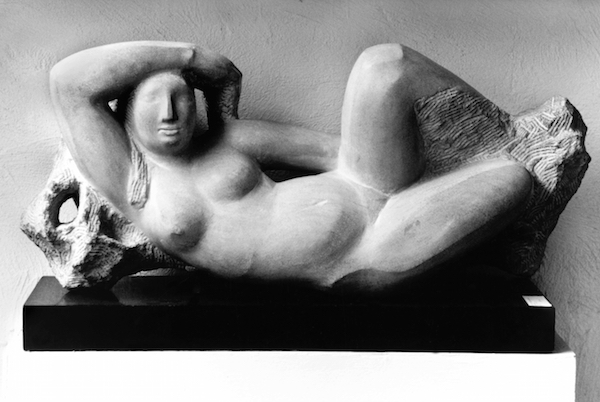

Goulet’s exhibition history dates back to 1948, including several Annual Exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and an installation at the New York World’s Fair of 1964/1965. From the beginning, it was Goulet’s ambition to create sculptures that would appear timeless and free of specific stylistic tastes. She never belonged to an art movement. In fact, in her sculpture, she always remained committed to one subject: the human figure. However, instead of realistically rendering its physiognomy, Goulet was interested in interpreting it. She was describing its potential, tracing fluid shapes and movements without a sense of weight or density. “I believe that anyone in the world can understand my work,” she said, stating that she wanted to make art for all people from all cultures. “I like the idea that someone in Borneo can access my sculpture as well as someone from my background.”

As a direct carver, she would take her material as-is and begin to work without making any preparatory studies or maquettes. “Direct carving is a way of life. It’s a way of seeing things,” Goulet explained. “That’s why I was always so reclusive — because I was concentrated on seeing; it was about complete immersion in my work.”

Goulet’s process required an extensive contemplation of the raw material, including its details, such as the grain of the wood or the veins in the stone, as each unique feature would impact the finished work. This might explain why alabaster, which possesses a range of rich natural colors and an unusual sense of translucence, counts among one of Goulet’s favorite materials. Each unique characteristic holds an inherent promise of potential. In fact, according to Goulet, “You see the potential when you look at the stone and you start to make forms. Everything begins to take shape and then you see the whole thing and you go towards that goal.” However, rather than superimposing an idea of form onto the raw material, Goulet was always interested in searching for something already hidden inside of it.

The female body — its sensuality, fertility, and embedded sense of strength — was a recurrent theme in Goulet’s work. In fact, instead of focusing on individual women or stylized goddesses, Goulet employed the female figure as an analogy for nature. “It is full, it is blossoming, it is progressive, it is giving; the female figure has all the qualities that I think are so important in sculpture. In fact, when you look at the history of sculpture, you find that artists have always used women. It carries on [in] my feelings about what sculpture should be.”

A prolific writer, Goulet’s philosophical and educational writings aid in formulating her vision. One of her past statements, which best sums up her take on the creative process and role of the artist, rings truer than ever when considering the entirety of her oeuvre today: “I believe the source of our art lies on our inner center of being… the core of our awareness. From this center flows our power of creativity, the mystery and magic of our art. I believe that art is the realization of the dynamic energy and order of the universe… as perceived by the individual… as reflected and made whole in the visual images we create.”

In addition to her work in the studio, Goulet looks back at decades of teaching. First, at the Museum of Modern Art’s Peoples Center, New York (1957), then at The New School, New York (1961-1975) and the Art Students League of New York (1981-2004). In fact, between 1964 and 1968, CBS aired 23 segments featuring Goulet’s teachings with demonstrations for children in a program entitled “Around the Corner,” which was sponsored by the New York City Board of Education. Today, Goulet continues her daily practice in the studio. Despite a stroke, which made it impossible for her to continue carving, she has not slowed down much. She now focuses primarily on painting while continuing to write poetry. When speaking with Goulet, one gets the clear impression that for her, it was always about making work with as little distractions as possible. “Often my studio door was closed and nobody knew what was going on. It was my peaceful niche.”

Luckily for the general public, examples of her work can be found in many major collections, including at The Whitney Museum of American Art, The Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and the Museo Nacional Centro De Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid.

“I was making beauty: beautiful sculpture,” Goulet reflected, adding, “The French philosopher René Descartes wrote that beauty was harmony, unity, and radiance — and I work with these three words. Radiance is the life, the ‘me’ that I put into the stone, and which of course gets lost over time. But the spirit I put in stays.”

For artist information, visit lorriegoulet.com.