By Albert Amateau

The reviews ran the gamut last Saturday when New York University officially opened its new version of the renowned Provincetown Playhouse on MacDougal St., where Eugene O’Neill presented his earliest works more than 90 years ago.

For theater folk, the interior of the vastly altered venue is a little, 88-seat gem, with space overhead for banks of lights, a green room actors’ lounge and two dressing rooms tucked under the sharply raked seating area — a far cry from the former, awkward, elevated stage with cramped dressing rooms below and a ceiling barely high enough to hang lights.

“I’m a theater person. I’m not interested in museum theaters,” said Peggy Friedman, a performer and executive director of the Washington Square Music Festival. “You used to be able to smell the mold,” said Friedman about the old Provincetown Playhouse.

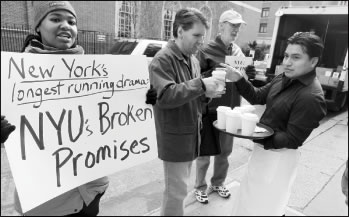

But for members of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation who demonstrated outside 133 MacDougal St. on Dec. 11, the theater space is a historic treasure despoiled by a renovation that demolished parts of the 170-year-old walls and failed to reuse or restore promised historic elements of the theater.

“N.Y.U. stop lying. Eugene O’Neill is crying,” chanted demonstrators led by Andrew Berman, G.V.S.H.P. executive director, who declared the playhouse renovation was another example in a long list of broken promises by the university.

The original playhouse, named for the theater in Provincetown, Mass., where O’Neill’s works were first performed, was in one of a row of four adjacent houses that were altered over the years, until in 1940, it morphed into a single, four-story, brick building with apartments on the upper floors and the 130-seat theater on the ground floor and basement at its southern end.

N.Y. U. acquired the building and playhouse in the early 1980’s. In 2008 the university rejected an N.Y.U. School of Law proposal to replace the building with an eight-story academic annex. Instead, the university decided on a five-story building, plus a setback penthouse, for use by the Law School. The decision included preserving the playhouse interior and its ground-floor facade with its characteristic round windows. The project, known as Wilf Hall, is not as tall as allowed by existing zoning.

However, in August 2009 during the reconstruction, a large part of the original walls had to be replaced and the original 1916 stage area had to be altered. Preservation advocates denounced the university’s failure to warn Community Board 2 and members of the Borough President’s Community Task Force on N.Y.U. Development about the necessary alterations.

But the new theater had won the praise of Village elected officials, including City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, Congressmember Jerrold Nadler, Assemblymember Deborah Glick, state Senator Tom Duane and Borough President Scott Stringer.

George Forbes, president of the Off-Broadway League, said in a prepared statement that the league was pleased by the preservation of the playhouse “at a time when small theaters are consistently in danger of permanently closing.”

At Saturday’s open house, music festival director Friedman said, “Now we’ve got a theater. We’ll see if N.Y. U. makes it available to the community.”

Joe Salvatore, who teaches educational theater at the university’s Steinhardt School of Education, said he was glad to be back at the playhouse this September after two years teaching acting and directing in swing space.

“The class that I just finished teaching here was the strongest that I can remember, and I think it was directly related to this new theater,” he said.

Salvatore is directing a program that will include “Fog,” an early O’Neill one-act play about seafarers, to be presented in the new theater Feb. 25 to 27 and March 3 to 6.

Another open house visitor, Leslie Kipp, a native Villager who still lives in the neighborhood and was involved in the successful community effort a few years back to block a teen lounge proposed for the Jefferson Market Library, said about the new theater, “I’m not so sure I like it. I like the old stuff.”

Out on the sidewalk in front of the playhouse, Berman protested that there was not much preservation in the project. The decorative cast-metal ends of seating rows that date back to 1940 were not replaced along the aisle, but are set into the walls — “entombed,” he said.

Berman also protested that there is nothing to prevent N.Y.U. from discontinuing theater use in the future, or enlarging the entire building at a later date to the maximum square footage allowed by zoning. In an open letter to elected officials, Berman asked that they seek a written commitment from the university to maintain theater use and not to use its maximum buildable air rights on the site.