BY SCOTT STIFFLER | You’re in candid and charming and proudly perverse company when watching a John Waters film with John Waters.

“Now this of course is one of my favorite scenes,” the writer-director notes on his audio commentary, just moments before Baltimore housewife Beverly Sutphin beats an annoying neighbor to death with a leg of lamb. “It has everything; murder, shrimping, dog abuse.”

Actually, the dog thing is up for interpretation. “No,” he quickly course corrects, “it wasn’t dog abuse, basically, because you just put butter on your toes and a dog will lick your toes all night — one thing we discovered.”

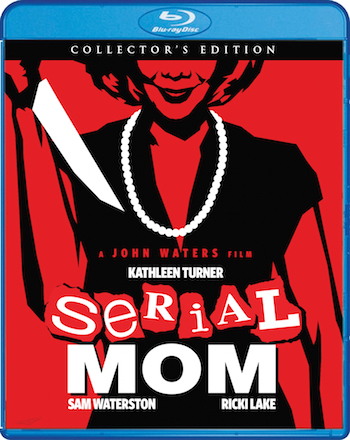

That odd little tip is among the many amazing facts and enlightening anecdotes awaiting the discovery of fetish neophytes and Waters completists alike, when they spend a few hours soaking in the bonus content on the Blu-ray collector’s edition of “Serial Mom” — just released from the Scream Factory imprint in time for, depending on her sense of humor, Mother’s Day.

Before exploring other revelations peppered throughout the extras on that well-appointed release, this publication had to ask a tough, nagging question at the onset of our recent phone interview with the director who filmed such startling acts as anal stimulation via rosary beads (1970’s “Multiple Maniacs”), feces ingestion (1972’s “Pink Flamingos”), and puke (see most of his oeuvre). Are there, we asked of the “Serial Mom” scene with those buttered-up toes, other cinematic instances of canine-on-human-shrimping?

“There are a lot of shots where dogs shove their nose in someone’s crotch,” Waters deadpanned, “but I don’t know. There could be. But off the top of my head? My dog-shrimping history? I don’t know that there’s another one; but I could be proven wrong.”

No matter. “Serial Mom” can certainly claim its share of unique moments, as well as unprecedented elements for a John Waters film: first sets to be built from scratch (interiors for the Sutphin home), first use of a stuntman (the concert immolation scene), highest budget ($13 million), and first casting of a mainstream Hollywood star in the lead female role. It’s also the most amount of money the director ever laid out for music rights (more on that later).

Released in 1994, “Serial Mom” is Waters’ sendup of suburban banality and true crime dramatizations. Turner, as the well-composed titular menace, bristles at the slightest indignity visited upon son Chip (Matthew Lillard as a blood and gore film fan), blossoming daughter Misty (Ricki Lake, who launched a successful talk show in Sept. 1993), and husband Eugene (Sam Waterson, giving a richly flummoxed performance familiar to fans of his work on the Netflix series “Grace and Frankie”).

SERIAL MOM’S STANDARDS SHARED BY HER CREATOR | “She’s the Breck Girl gone crazy,” says Waters in the making-of featurette, when commenting on Turner’s cheerful but easily crossed mother — who secretly purchases books with titles like “Helter Skelter” and “Hunting Humans,” corresponds by cassette tape with Ted Bundy (Waters, in an uncredited voice-over), and phone pranks her divorced neighbor Dottie Hinkle (Mink Stole) into uttering obscenities.

“She thought she was doing the right thing,” Waters told us. “Serial Mom had the right morals, she was just… well, talk about a reactionary.” Stopping short of condoning the ultimate punishment Sutphin doles out more times than you can count on one hand, the character’s creator readily admitted, “I agree with some of the stuff Serial Mom does, like no white after Labor Day.” Waters noted he’s also in the “no velvet before Thanksgiving” camp, adding, “I’m right wing on fashion rules.” Like wife-of-a-dentist Beverly, who makes a visiting detective spit out his gum, Waters told us, “I hate it. It makes me crazy if somebody’s sitting next to me on a plane chewing gum. I feel like I could drag them off, like United Airlines. That’s what I want to do when I see them, without asking them; just grab them by the feet, pull them right out of the chair and up the aisle, right to the jetway. Chew your gum there.”

Vivid daydreams of assault, righteous though they may be, seem to come easy to Waters, whose director’s commentary to the film notes, “I have a huge true crime library, probably one of the better ones in America; and I thought, God knows I know about this stuff. But nobody had ever made a movie that I could think of where you rooted for the serial killer to kill more.” Waters goes on to recall the casting of Patricia Hearst, as a juror who runs afoul of the aforementioned fashion stance regarding the seasonal shelf life of white. It’s Hearst’s second appearance in a Waters film (following 1990’s “Cry-Baby”), and the bonus content includes the backstory of how they met. Waters, who attended her 1976 trial, opines on the etiquette of courtroom hag subculture, and Hearst recalls the phone conversation they had during the June 17, 1994 O.J. Simpson white Bronco chase.

MINK STOLE TALKS TECHNIQUE AND TONE | What remains the most famous slow police pursuit in history happened just two months after the release of “Serial Mom” — which, longtime Waters ensemble member Mink Stole noted when we spoke with her by phone, contains an eerily predictive scene (the Sutphin family is followed by a phalanx of police cars as they slowly drive to from home to church).

“There’s a shine on it,” Stole said of “Serial Mom,” which she called “polished in a way that none of his other films are. I watched it a couple of days ago for the first time in years and it holds up. There’s not a wrong note or an extra beat; it just works. I think you can credit Kathleen for a lot of that,” Stole noted, “but you can also credit John” for “a gradual progression over the course of the years. I mean, we started out in eight millimeter [film stock], and now, here we were in 35 millimeter; and we had money! When we were making ‘Multiple Maniacs,’ there was no money for reshooting. You had to remember your dialogue from beginning to end. With ‘Serial Mom,’ we had the luxury of being able to afford retakes.”

Stole said her performance was also a dip into uncharted waters, so to speak. “This was the first movie where John would tell me to take it down,” she recalled, “which was interesting, and an unexpected challenge. What was wonderful about this movie was, there’s an element of restraint to it. Even the scene in the courtroom where I scream and lose control is not the same kind of lunacy as, say, ‘Desperate Living.’ I was aware that the whole film was understated, which is a total departure for John.”

Stole’s was especially aware of abiding by that tone in the early phone prank scene, which sets up Stole’s Dottie Hinkle as innocent but easily goaded, while firmly establishing the cat and mouse sadism of its lead character (also notable in the commentary version of this scene is Waters’ nod to 1959’s “Pillow Talk” as the source of his affinity for the split screen technique).

“People do like it,” Stole said of the foul-mouthed exchange, in which Sutphin masquerades as a phone company rep who requires Hinkle to use the obscene language she’s been subjected to by her mysterious caller (Serial Mom, of course). “I had to allow myself to be pulled into her sphere,” Stole recalled of working with Turner, “rather than her into mine, and that was great for me.” A later scene, again with Turner as well as Mary Jo Catlett as nosy neighbor and fussy Franklin Mint Faberge Egg collector Rosemary Ackerman, was “like being shot out of a cannon,” Stole said. “I was working with two women I consider consummate professionals. I didn’t want to be bad, and that made me nervous. But Dottie was a little stiff anyway. She had a personal rigidity, so I was able to incorporate that.”

Taking it down more than a few notches paid off. Waters, during the feature commentary version in which both he and Turner watch the film, said of Stole, “I think this is my favorite role she ever did, actually. … The very first day in rehearsal, when I heard Mink calling Kathleen a cocksucker in my living room, I knew my worlds had come together.”

THE HIGH COST OF HIT MUSIC | Now back to the matter of what a $13 million budget can buy. That scene with Turner wailing on her neighbor with a leg of lamb (a favorite dish of Waters’ mother) happens as the victim settles in to watch a VHS copy of “Annie,” which she’s told video store clerk Chip Sutphin she won’t be rewinding. The murderous deed happens to the tune of “Tomorrow,” which, on the director’s solo commentary track, Waters pegged as costing $60,000-$70,000.

“I don’t know why they just didn’t’ say no,” he told us, about the process of acquiring music rights. “I’ve had many people say no before. They ask for content and I think, oh Christ, there it goes, they’re going to say no. But I think they gave us a really high price, thinking we would say no, because not only do we murder the song, but Kathleen even kills a woman with a leg of lamb in beat with the music, in time. So I think it was worth the money.”

“I don’t know why they just didn’t’ say no,” he told us, about the process of acquiring music rights. “I’ve had many people say no before. They ask for content and I think, oh Christ, there it goes, they’re going to say no. But I think they gave us a really high price, thinking we would say no, because not only do we murder the song, but Kathleen even kills a woman with a leg of lamb in beat with the music, in time. So I think it was worth the money.”

Also of note is the 1976 pop tune “Daybreak,” which Serial Mom sings along with during a high-stress driving situation. “I just thought that Serial Mom would like Barry Manilow’s music,” Waters told us. “I mean, I like it. But ‘Daybreak’ was a mainstream, Middle America hit; and good for him! Barry thought it was funny. He was totally for it.” On the commentary with Turner, Waters recalled, “Later, I got, from Barry, an application to get a Barry Manilow MasterCard.” Pressed for details during our interview, Waters confirmed it wasn’t mere junk mail, but a personal invite from Manilow himself. “I don’t know if it was a joke or not,” Waters said. “I didn’t get one because I already had a MasterCard, but I should have. If I have one regret, it’s that I didn’t get a Barry Manilow MasterCard.”

The “Serial Mom Collector’s Edition Blu-ray” ($34.93) is available now on retail shelves and via Shout! Factory’s genre entertainment imprint, Scream Factory (shoutfactory.com). Bonus material includes two feature commentary tracks (one from Waters, one with Turner and Waters); a “making-of” featurette; a conversation with Waters, Stole and Turner; a “Serial Mom: Surreal Moments” compilation of interviews with cast and crew; the original theatrical trailer; and the featurette “The Kings of Gore: Herschell Gordon Lewis and David Friedman.”