BY ANDREW BERMAN | In late June we learned that the state Assembly and Senate had passed legislation that, among other things, allows the sale of air rights from piers within the Hudson River Park for development one block inland, with the money from the sales to be used to fund the park. This startling news has raised serious concerns about exactly how much additional development this will lead to, where and what the impact will be.

Unfortunately, none of the answers to these questions are fully clear yet, in part because of the complicated rules governing development in New York. But it’s also partly because very little analysis of these questions was done prior to the Legislature’s approval of this measure, and because exactly how this will ultimately play out still remains to be seen.

This legislation may not, in and of itself, result in a wall of skyscrapers bordering the park. But, at the very least, it may facilitate substantially larger development on the blocks bounded on the west by West St., all the way from Chambers St. to 59th St. Worse, it may open the door to, and provide an incentive and rationale for, rezoning parts of our neighborhood to permit even larger development than just the air-rights transfers, in themselves, would allow. And it is yet another step toward requiring real estate development as the price for securing public amenities and infrastructure — a disturbing trend which has become increasingly common in New York City in recent years.

While it is unclear exactly how the transfer of air rights from park piers will ultimately play out, the scenarios range from worrisome to much worse. The worst-case scenario is that the legislation has already made air-rights transfers immediately possible from piers within the park to inland sites for development. Most of those behind the legislation, including state Senator Brad Hoylman, who voted to approve the measure, and Assemblymembers Deborah Glick and Dick Gottfried, who sponsored it, believe this is not the case. I am hopeful that this is true. But there is enough ambiguity in the language of the legislation that further investigation is needed to conclusively prove this — especially given that state legislation trumps New York City zoning rules, and it is those city zoning rules that the bill’s authors claim prevent the use of the pier’s air rights inland right now.

But even in a best-case scenario, approval of this legislation was the first step in a two-step process to allow these air-rights sales and transfers to take place. And this decision was made with virtually no notice to or consultation with the affected inland communities, outside of some discussion within committees charged with overseeing the development of the Hudson River Park (and even many members of those committees have said they were completely blindsided by this plan).

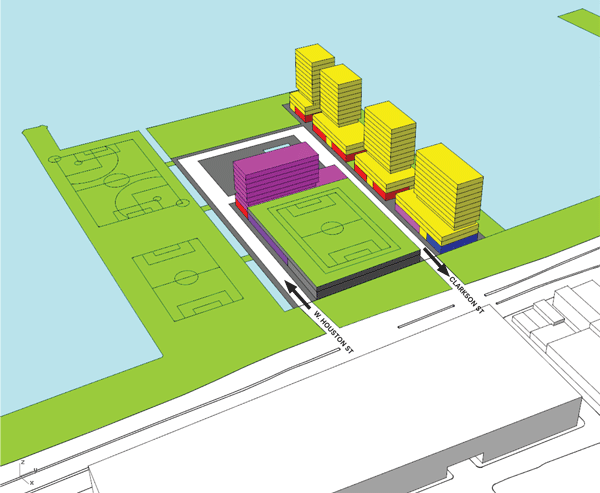

In response to the questions we have raised, the Hudson River Park Trust has recently put forward a figure of around 1.6 million square feet as the total of unused air rights currently available under this new rule. To give you some sense of how much this is, the 30-story towers of N.Y.U.’s Silver Towers complex on Bleecker St. — currently some of the tallest and most prominent buildings in the Village — are about 200,000 square feet each. So 1.6 million square feet would be the equivalent of eight more of these towers that currently dominate the skyline of the Village.

But there is reason to believe that the amount of potential air rights ultimately may be even greater. The 1.6 million-square-foot figure is based upon current conditions on the piers. But some of these piers, such as Pier 40, at W. Houston St., may eventually have some or all of their structures (pier sheds) removed, or replaced with smaller ones. The current Pier 40 structure is several hundred thousand square feet; so if even just part of the structure is eventually removed — say, 200,000 square feet — that creates an additional 200,000 square feet of air rights that, under this new legislation, could be transferred inland for development on those neighboring blocks.

The 1.6 million-square-foot figure also assumes that only those piers that are designated as “commercial” piers, such as Pier 40, Chelsea Piers and Pier 76, among others, have air rights, and that “recreational” piers, such as those at Christopher, Charles and Jane Sts., do not. But this is based upon interpretations of zoning regulations by the city, and the city has been known to change such interpretations before. In recent years, for instance, the city has reinterpreted zoning rules to allow “condo-hotels” in manufacturing zones, and to allow air rights from properties restricted to community uses to be used for private condo development. More importantly, we’ll soon have a new mayor, which means those in charge of making these interpretations will soon be changing, as well. While a new mayor does not have unlimited latitude in this regard, there is room to maneuver on these sort of development and zoning issues, and past mayors have certainly done so before.

But even if the amount of air rights are exactly what state legislators and the Hudson River Park Trust are currently telling us, and their use on inland blocks would still require an additional city or state action, this is not very reassuring. Neither a city rezoning (a “ULURP”) or a “general project plan” by the state — the next-step processes that would be required to use the air rights — guarantees a favorable outcome for the community. In fact, experience has shown just the opposite is more likely the case.

And both the city and state processes are ultimately controlled by forces far beyond our neighborhood. A rezoning initiated by the city or a private developer is decided by appointees of the mayor, the five borough presidents and the 51 members of the City Council, who may have a very different view of what is right for our community than we do. And a “general project plan” by the state is decided by forces even farther removed from our community, in Albany. Both processes involve limited, if any, community input, and we have seen how community input can be ignored in city rezonings, as with New York University’s expansion plan.

But perhaps most disturbingly, this new mechanism creates a strong incentive for our current zoning to be reopened to not only allow the transfer of air rights from the piers — which would allow larger development inland to fund the park — but to go beyond that and allow even greater development in our neighborhoods as part of the deal. Based upon experiences in recent years, it is easy to imagine a scenario in which we will be told that in order to get the “benefit” of an air-rights transfer from the piers to fund the Hudson River Park, we will have to accept a zoning change with additional, undesirable elements — whether it be even larger development, undesirable uses or zoning changes elsewhere. This has been the consistent pattern in most, though not all, rezonings put forward by the city when some public benefit is attached.

I don’t mean to imply that the entire picture emerging from the adoption of this air-rights transfer provision is automatically doom and gloom. Is it possible that limited air-rights transfers could be allowed to sites one block inland where larger development than currently allowed is appropriate? Could the tradeoff ultimately be worth it to help the park? Is it even possible that as part of the rezonings or “general project plans” that may be necessary to allow this to happen, other benefits could be afforded our community, or other positive changes made to development rules in our neighborhood?

It is possible. And that is exactly what those who made this air-rights transfer provision possible now have a responsibility to ensure happens, should this provision be used.

But frankly, that will be no easy task. And with this new development-rights transfer legislation, our ongoing fight to preserve the scale and character of our neighborhood, especially along the waterfront, just got a good deal more challenging. This new provision has opened a proverbial Pandora’s box of development potential. And in our heavily real estate industry-influenced city, the outcome of that is, I believe, much more likely to be bad than good.

Berman is executive director, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation