BY NORMAN BORDEN | With the eagerly anticipated opening of its new museum space at 250 Bowery now a reality, the International Center of Photography (ICP) has come a long way, both physically and philosophically, since it was established by Cornell Capa on Fifth Avenue’s Museum Mile in 1974. Capa’s intent had been to preserve and promote the legacy of the “Concerned Photographer,” a term he used for any photographer passionately dedicated to doing work that contributed to the understanding and well-being of humanity, which included photojournalists and street photographers.

Over the years, as photography gained in stature as a fine art, ICP’s influence also grew. When it moved to a larger space on Sixth Ave. in 2000, the Internet and digital technology were in their infancy. ICP embraced the new, but did not trash the old. In fact, its mission statement said, “ICP is expanding to encompass the new electronic imaging media which will shape the 21st century just as photography did the 20th.” (But who could have predicted that over one trillion digital photos are now taken annually?)

ICP’s sprawling new exhibition includes 150 works by 50 artists that occupy both floors at 250 Bowery, demonstrates just how far the institution has come — and, more importantly, where it’s going. In the age of selfies, Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram, “Public, Private, Secret” explores how self-identity has become tied to public visibility.

Given that millions of people around the world now produce and exchange images to communicate complex ideas about everything from urban policing to self-identity, Mark Lubell, ICP’s Executive Director, noted, “The new ICP Museum space was specifically designed to foster shared dialogues about these issues and the opening exhibition is a perfect example of this, addressing one of the most critical conversations in today’s post-Internet society: privacy.”

Explaining the show’s evolution, Charlotte Cotton, ICP’s first Curator-in-Residence, told of a conversation with Lubell while the new space was being built out, during which she expressed her interest in keeping ICP very strongly involved with the social implications of the visual culture. “I wanted to approach it as a social issue rather than from the fine art perspective that most institutions would take.

When he suggested doing a show about privacy, Cotton said she could live with that subject. “We’re all worried about our privacy to some degree and I was interested in doing a show that would ask you to deal with it in a personal way. I wanted the look and feel of the exhibition to deal with your own body in the space.”

Recognizing that all information can be found online, she knew there would have to be a really good reason to visit a physical space, She says, “I liked the idea that we were creating an exhibition that was an experience. You have to be here to get it — you can’t see this at home.”

In curating the show, Cotton had some clear ideas about what it should and shouldn’t be. “I didn’t want to do a surveillance exhibition with drone pictures,” she says. “I didn’t want to fetishize anything. Among the things I picked were historical works that were really at the roots of issues we’re facing today, like early mug shots, Weegee, and the paparazzi.”

Asked if she could imagine what Cornell Capa would have thought about this new ICP, Cotton smiled and said, “I think he would have been most proud of the communal space that’s free and open to the public. It doesn’t feel like a museum lobby, but it’s all about access.” Designed to be like a village square, the space has a clock, cafe, comfortable seating, a bookstore, and a bulletin board — all visible from the street through floor to ceiling windows. Workshops, some free, are planned to start in the fall. The hope is that visitors won’t just visit ICP to look at exhibitions, but also come for conversations about photography.

“Public, Private, Secret” will certainly give visitors a lot to talk about. Privacy is a complicated subject, and so is this show. In the main gallery downstairs, the work is loosely organized into three categories: public, private, and secret — and the historical and contemporary work often appear side by side. For example, in the “public” category, 1979’s “Untitled,” by Cindy Sherman (known for her self-portraits), is juxtaposed with a video of “Selfish,” Kim Kardashian’s 2015 book of selfies.

Next to it is a series of Andy Warhol self-portraits framed with mirrors. In effect, you’re looking at yourself looking at Warhol. And mirrors are used elsewhere in the exhibition as a framing device, a clever wink to the narcissism that surrounds so much of today’s picture taking.

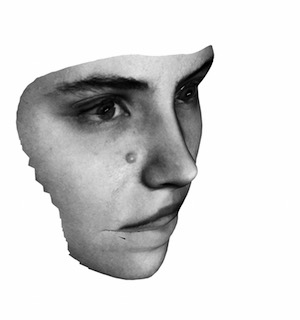

Surveillance and privacy, or the lack of it, come together in a juxtaposition of a poster-sized Weegee photograph of prisoners using their hats to cover their faces, placed next to “The Revolutionary,” from the 2013 “Spirit Is a Bone” series by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin. They created portraits of a broad spectrum of Moscow’s citizenry by adopting a facial recognition system used by the Russian government to identify individuals at demonstrations and in other public places.

Voyeurism has its place in the privacy discussion, as revealed in historical works by Henri Cartier-Bresson (“Mexico,” 1934), Gary Winogrand, (“Women are beautiful,” 1975), and Polaroid photos by unidentified photographers of auditions for Playboy magazine that are covered by a canvas drape, so lifting it up turns the viewer into a voyeur.

Underscoring the exhibition’s 21st century sensibilities are streams of real-time images and video on display in the downstairs gallery. Curated by Mark Ghuneim, the feeds use various social media as sources of content, and are organized by themes such as “Hotness,” “Morality Tales,” “Celebrity Leaderboard,” “Transformation,” and “Privacy.” An algorithm changes content about every 15 minutes.

As a non-Millennial, I thought “Testament,” by Natalie Bookchin, was more mesmerizing than the video feeds. It’s a powerful series of collective self-portraits that the artist made from a montage of video diaries she found online. Using topics such as unemployment, sexual identity, and psychopharmacology, Bookchin edited and sequenced the clips from different people — so the effect of her work sounds like a well-synchronized Greek chorus or choir. You can’t see this at home.

Like the show itself, ICP’s re-opening downtown was overwhelming — there were some 6,000 visitors during its first four days, a welcome surprise. With those numbers, a thought-provoking exhibition, and a different kind of museum space, ICP is off to a good start.

“Public, Private, Secret” is on view through Jan. 8, 2017 at the International Center of Photography (250 Bowery, btw. Houston & Prince Sts.). Hours: Tues., Wed. & Fri.–Sun., 10am–6pm; and Thurs., 10am–9pm (6–9pm, pay what you wish). Admission: $14 (seniors, $12; students, $10; free for children 14 & under). Call 212-857-0000 or visit icp.org.