The 19th-century Manhattan waterfront was an exotic olio of wares shipped from all over the world, imaginative shop signs and carved, wooden statuary placed in front of stores so that passers-by would know what goods were available within. These artifacts are part of the “Compass: Folk Art in Four Directions” exhibit, on view through March 31.

BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | Like a stout ship that was buffeted by a severe ocean storm, the South Street Seaport Museum came through Superstorm Sandy battered but fundamentally intact.

The museum’s elevator and escalator no longer work. To see the exhibits, it’s necessary to climb the stairs of the early 19th-century buildings on Schermerhorn Row that house the galleries. But happily, the museum’s collections weren’t damaged — and some special exhibits that would have closed by now, had Sandy not intervened, are still on display.

“Compass: Folk Art in Four Directions,” an exhibit drawn from American Folk Art Museum’s 19th-century paintings, sculptures, carvings and other artifacts related to the maritime history of New York City, was supposed to have closed in early October. Now, the closing date is March 31.

Another exhibit, “Romancing New York,” of watercolors by Frederick Brosen, was also supposed to have closed by now. It was held over from its original closing date of Jan. 6, 2013 and will close on March 10.

For the “Compass” exhibit, four galleries are arranged around the themes of exploration, social networking, shopping and the environmental conditions that affected ships and the men who worked on them.

Voyages aboard commercial sailing ships often took three to five years. The exhibit depicts the men who went to sea, the women who waited for them to return and the children who grew up — and in some cases, died — while their fathers were away.

It also shows some of the fancy goods that the ships brought to New York City from all over the world and the comfortable life that this commerce enabled, at least for some. One room of the exhibit contains portraits of fashionably dressed women, children with expensive dollhouses and other toys and hand-painted furniture embellished with gold leaf.

As sailing ships gave way to steam, the workshops that had formerly carved ships’ figureheads had to find new sources of revenue. Larger-than-life statues that once stood outside tobacconists’ shops display the craftsmanship of some of these late 19th-century carvers.

One of the most prominent artisans was a man named Samuel Anderson Robb, who had studios first on Canal Street and later on Centre Street. Several pieces from his workshop are in the “Compass” show, including a Sultana dating from around 1880 who stands with her right hand held aloft — reminiscent of the Statue of Liberty, but holding a bunch of cigars instead of a torch.

Much of the last gallery of “Compass” revolves around the wind and weather that were the linchpins of maritime life. Weathervanes were an important addition to the rooftops of many buildings. Though a necessity, they were also frequently decorative.

One in the exhibit is particularly elaborate, depicting a horse-drawn fire engine. It was made around 1880 of copper and zinc with traces of gilding. The description notes that early structures in the seaport and Wall Street areas of Manhattan were usually made of wood rather than bricks, which were expensive. “Firefighting equipment was of paramount importance but did not prove effective on a winter’s night in 1835, when the water froze in the hoses and fire swept through lower Manhattan, destroying more than 600 structures,” says the descriptive sign next to this weathervane.

On the floor above “Compass” is a gallery holding an exhibit of the woodcarvings of a self-taught artist named Mario Sanchez who lived in Key West, Fla. and who portrayed the world of his early 20th-century childhood in his carvings.

“A Fisherman’s Dream: Folk Art by Mario Sanchez” was supposed to open on Nov. 8, 2012 and run through Dec. 31, 2012 — but the South Street Seaport Museum’s shaky electrical and heating systems, severely damaged by Sandy, delayed the opening. Finally, the exhibit opened on Dec. 14 and will be in place through March 12. The show was mounted by the South Street Seaport Museum in partnership with the Key West Art & Historical Society (where Sanchez worked as a janitor) and the American Folk Art Museum.

The 43 bas-relief carvings in the show sketch out a sunny world where women stood on a street corner and gossiped, fishermen sold their catch directly to local residents and a horse-drawn ice wagon passed by, carrying blocks of ice delivered by a sailing ship that came to Key West from Maine. One carving shows the grocery store that belonged to Sanchez’s grandfather. In that same carving, he depicted his mother, Rita, sitting on a porch with himself and his older brother next to her. On the back of that picture, he noted that when he created it in 1971, she was still alive and 85 years old.

In this tranquil world, there were intimations of change. One carving shows a train from the Florida East Coast Railway belching smoke as it passed above a little island where men sat around a card table, a woman tended her chickens, a man fished with a pole and a child and dog raced along the beach. The trains brought people from New York City to Key West. When the tracks were washed away by a hurricane in 1935, they were replaced by a highway that allowed cars to access the island for the first time.

The most famous of Sanchez’s works is called “El Galano” — a depiction of an old fisherman alone in his boat. Sanchez based it on Ernest Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea.” Spencer Tracy, who was nominated for an Oscar for his portrayal of the old fisherman in the 1958 film of the book, once owned this carving and gave it to Katharine Hepburn. On the back of it, Sanchez wrote a poem about the old man.

In fact, several of the carvings have notations on the backs and they are very much worth reading. One of them provides some information that is not on the descriptive card in the front of the carving. Called “The Lucky Fish Rhumba,” it shows some strangely clad people in black hoods and cloaks on a Key West street.

“This is an initiation dance of Nanigos, a secret voodoo cult which customarily held it ceremonies on Whitehead Street, Key West,” says a typed note on the back of this carving (spelling and grammar, as written). “The participants used a half-dead chicken or fish in their rites and their gesticulations became more and more Afro as their native music rose to a high pitch.”

Photographed in 2010, Matt Weber’s “Coney Island” is part of the “Street Shots/NYC” exhibit, on view through April 5.

The carving had a price tag of $350.

Next to Sanchez’s gallery of memories is another gallery with the remarkable watercolors of Frederick Brosen. In these pictures, he shows historic structures of Lower Manhattan and the kitsch of Coney Island, creating a world of complete stillness. Nothing moves — not a person, not a car, not a leaf, not a bird. Nothing.

These paintings might seem photographic at first glance, but they are not. Brosen works on his pictures with meticulous care, studying his subjects carefully over a period of time, then drawing them and finally applying the paint. They envelop the viewer as they must have enveloped him in the making of them. He has said that a single painting may take him 10 weeks to create.

Also on this floor of the museum is an exhibit of photographs called “Street Shots/NYC” with images from 125 professional and amateur photographers of the city’s kaleidoscopic street life. A red dress hangs from the fire escape of a tenement. An enormous American flag is draped over a building on Mott Street. A baby howls as its mother tries to take a picture. In a photo called “NYC Morning Walk Home,” a woman in a short, tight skirt and high heels passes an elderly, white-bearded Jew with his prayer books under his arm, who looks at her askance.

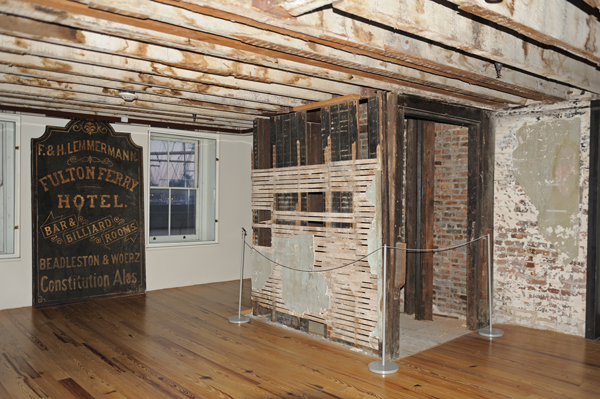

The South Street Seaport Museum on Schermerhorn Row once housed several hotels for seamen. In 1952, the writer Joseph Mitchell and Louis Morino — who owned a restaurant called Sloppy Louie’s on this site (92 South St.) — used this old elevator shaft to enter the boarded-up Fulton Ferry Hotel (in operation from 1874 to 1935), where they found iron bedsteads, bureaus and a sign reading “All Gambling…Strictly Prohibited.”

“Street Shots” will be at the museum through April 5.

Finally, on this floor, visitors can glimpse one of the most intriguing parts of the South Street Seaport Museum — the remnants of the old hotels that the Schermerhorn Row buildings once housed. By the time these buildings had been turned into cheap hotels, they had definitely come down in the world.

That the six buildings of Schermerhorn Row were built of brick and not wood says something about the affluence of their builder and the importance of the project. Peter Schermerhorn erected them in 1811-1812 to serve as counting houses for the seaport merchants. At the time, they were among the largest and most imposing structures in the city.

Over the ensuing decades, they were repurposed as warehouses with stores on the ground floor. Several hotels for seamen and traveling salesmen opened in the buildings in the latter part of the 19th century.

On the fourth floor of the museum, visitors can see what remains of an elevator shaft through which the writer Joseph Mitchell and the restaurateur Louis Morino (owner of Sloppy Louie’s on the ground floor of 92 South Street) ascended in 1952 to the boarded-up third floor of the building, formerly occupied by the Fulton Ferry Hotel. There they discovered discarded iron bedsteads, bureaus, seltzer bottles and signs reading, “All Gambling…Strictly Prohibited” and “The Wages of Sin is Death.”

Mitchell wrote about this in his famous article, “Up in the Old Hotel.”

Visitors can still see the hotel’s laundry room with its racks for drying linens, its large tubs, and its mangle for pressing excess water from the wash — and they can also see the cubicles in which the guests slept, with strips of faded wallpaper still hanging from the partially exposed laths.

No exhibit in the museum is more evocative than the very structure of the building itself.

THE SOUTH STREET SEAPORT MUSEUM

12 Fulton St., btw. Front & South Sts.

Open daily, 10am-6pm

Admission: $10, free for children under 9

Call 212-748-8600 or visit

southstreetseaportmuseum.org