BY AMANDA MORRIS | Dozens of silver police barricades lining Centre and Lafayette Sts. barely contained the crowd of hundreds of protesters that gathered in Foley Square on Nov. 10. The boom of activist speakers’ voices reverberated throughout the streets of the Financial District.

“How can we thrive if we are unable to survive?” Rahel Teka, a young female activist, thundered over the loudspeaker.

“Without us,” she said, getting louder, “there is no America, so it’s up to America to make sure that we survive!”

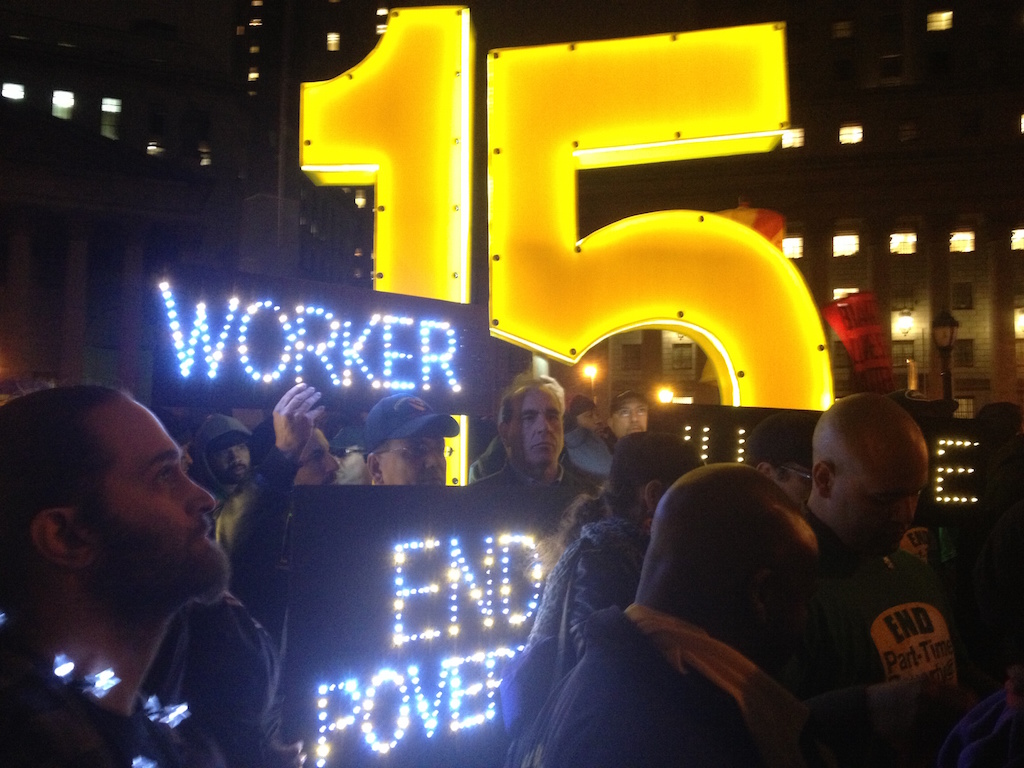

The crowd roared their approval and hoisted their signs higher into the air. Among them were the tall purple banners of the 1199 SEIU healthcare workers union and the small blue circles of the Hotel Trades Council. The biggest of these signs, however, was a massive yellow lighted sign surrounded by Teamsters 804 UPS union members. Working together, the members hoisted their 5-foot-tall sign into the air and suddenly a bright 15 rose above everyone’s heads. This 15 served as an emblem for the continuing Fight for Fifteen movement, which is pushing for a $15 federal minimum wage.

The protesters had been standing in the cold, dark, rainy weather since 4 p.m., but three hours later, the party had just begun. A full marching band played upbeat music and walked up Centre St., followed by two dancers decked out in sparkly silver pants, and a slew of minimum-wage workers from all different professions bopping along to the music.

“What do we want? Fifteen!” they chanted. “When do we want it? Now!”

The march concluded at Bowling Green roughly two and a half hours later. It coincided with protests in 500 cities nationwide to be the biggest Fight for Fifteen demonstration yet, according to the effort’s eponymous official Web site. What started two years ago in New York City as a fast-food worker movement for higher wages has now blossomed into a multi-industry minimum-wage worker alliance.

This new alliance is pushing for a federal minimum wage, as well as more union rights across various job fields.

“Nov. 10 was about flexing their political muscles — taking the victories in New York and using it to leverage it for victories elsewhere,” a spokesperson said.

The protest was timed to be held exactly one year before the 2016 presidential elections, and minimum wage has been one of the issues that various candidates have focused on throughout the campaign. In both the Republican and Democratic debates, candidates have been asked about their position on minimum wage.

In New York City last spring, the Fight for Fifteen had “a big win,” when Governor Andrew Cuomo and a wage board increased wages for fast-food workers to $15 an hour in New York and later extended this wage increase to cover state workers, as well. Fast-food workers’ first wage increase, to $10.10 per hour, will come on Dec. 31.

In even bigger news, this week, Cuomo said he backs a $15 minimum wage statewide, and Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the wage would apply for 50,000 city workers, though not starting till 2018.

Still, for some, these wage increases aren’t coming fast enough. Kenya (not her real name) is an outgoing 22-year-old cashier from Brooklyn who works at McDonald’s and frequently has trouble paying her bills on a minimum-wage salary. While attending to her fussing 2-year-old daughter in the background, Kenya sighed over the phone during a recent interview.

“I have to choose between putting Pampers on my daughter’s back, food on the table or paying my mortgage,” she said.

Kenya is only able to work part-time to make roughly $500 per month. Yet her mortgage is $431 per month. Often she doesn’t pay her mortgage and is constantly in debt.

“I haven’t been able to save any money,” she said. “I don’t even have a bank account because I always end up using my money for something.”

Before dropping out of the Borough of Manhattan Community College, Kenya aspired to become a pediatrician. However, after a surprise pregnancy forced her to find any job she could, her current dream is just to be independent.

“I’d rather have it together for myself so that I don’t have to depend on anyone,” she said.

She is pushing for a union because she depends on her job for survival.

“I really need a union for protection from being injured out of my job or fired,” she added.

Others, such as Yvette Frazier, a low-wage worker/activist in the NYC Communities for Change organization, which advocates for a range of social and economic justice issues, believe that unions are necessary to make sure that workers are getting fair hours.

According to Frazier, one tactic that some companies may use is keeping workers just under the 40-hours-per-week mark in order to classify them as part-time workers, who get fewer benefits.

“I know people who aren’t allowed to do overtime anymore,” she said. “I know people who can’t even get paid for 40 hours a week like they deserve.”

Frazier currently works as a patient escort (she drives patients around), but previously she worked as an in-home helper for patients, which meant feeding, dressing, cleaning and looking after them, for $10 an hour. As a live-in, Frazier was paid for 13 hours a day, despite extra hours that she often put in.

“I had patients who would keep me up all night but I only got paid for 13 hours,” she said. “It’s not fair. We just want more rights. Fifteen dollars an hour is a drop in the bucket for the work we do. We do the hardest work for the least amount of respect and we get the least pay.”

The potential for workplace abuse grows even greater with undocumented workers, such as in the case of Myungsoon Choi, 58, who came to the U.S. 10 years ago from South Korea and currently works as a cook at a Korean restaurant in Flushing, Queens.

“The biggest challenge that I face is the fact that I am undocumented,” Choi said through her daughter, Jung Rae, who acted as translator. “I am not qualified for health insurance, unemployment insurance or retirement plans. Limited language capacity and undocumented status make it hard for me to find work that pays well.”

Since Choi’s ability to find work is limited, she previously was forced to work jobs in which, she said, she was, “required to work overtime during holidays with no extra pay rate as mentioned in labor laws.”

At her past jobs, Choi, a single parent, made minimum wage and had difficulty supporting her son and daughter. Now, at her current job, working 10 hours a day, six days a week, Choi makes more, roughly $2,400 a month. But that’s still not enough for her to make ends meet.

“My current wage is not enough to cover living expenses,” she said. “Sometimes I have to get physical therapy for elbow pain out of my own pocket as I do not have health insurance.”

However, raising the minimum wage isn’t the only battle that low-income workers have to fight. Raising education standards, while dropping tuition, may even be more crucial, some think. New York University senior Robert Ascherman studies social movements and gave a speech at the Nov. 10. rally. Ascherman works closely with the Fight for Fifteen movement and serves as the president of the Student Labor Action Movement, or SLAM, activist organization at N.Y.U.

SLAM has been pushing for higher wages for students in order to make education more accessible. The average four-year public school tuition, according to the 2015 College Board report, is currently $9,410, with the total cost rising to $19,548. For a private school, the costs are even higher, and at N.Y.U., some students work to try and pay off their loans.

“Students are trying to work two or three jobs to get through school when they’re supposed to be doing homework or studying,” Ascherman said. “It’s just not possible to make it work.”

Ascherman added that the barrier for education is higher for low-income families.

“People can’t afford to stop working and go to college to get a better job if they constantly have to work to survive,” he said.

This is a problem that Choi has faced in attempting to learn English.

“Because she works six days a week, it is virtually impossible for her to find an English class that fits her schedule, which creates a barrier for her to learn English,” her daughter, Rae, said. “Tutoring or English schools are also expensive for working-class immigrants.”

However, raising the minimum wage might actually do more harm than good, according to N.Y.U. economics professor Christopher Flinn, author of the book “The Minimum Wage and Labor Market Outcomes.” While Flinn agrees that education should be more affordable, he doesn’t believe that raising the minimum wage is the best way to increase access to education.

“Fifteen dollars is not nirvana by any means,” Flinn said. “It’s not going to get them out of poverty. The only way to break the cycle is to raise the skill level of workers.”

According to Flinn, having a higher skill level will allow workers to transition into higher-paying jobs.

“If you don’t raise skill level then employers are doing charity work at some level,” he noted.

Flinn believes it’s unfair to pay $15 per hour to a low-skilled worker, arguing that minimum-wage jobs were “never intended for supporting a family, nor thought of as a career.”

The long-term fix, according to Flinn, is to raise the skill level of high school graduates by fixing America’s public K-through-12 education system.

“The real culprit is a bad schooling system,” he said.

Even more to the point, Flinn suggested that the biggest change would come from creating better affordable pre-school and early-education programs.

“By the time kids are five years old, there’s already a huge difference in their prospects just based on their family and school environments,” he said.

Flinn added that the raising minimum wage is only a short-term fix that will actually end up causing more unemployment. Using mathematical models, he has predicted that if the minimum wage were to almost double to $15 an hour, roughly 50 to 60 percent of the affected jobs would go away.

These assertions are supported by the 2014 Congressional Budget Office report, which predicted that raising the minimum wage to $10.10 would reduce employment by about 500,000 jobs by the second half of 2016.

“Companies are going to react like they did in Sweden,” Flinn said. “They’re going to hire less workers and have more automation. You’ll go into McDonald’s and order through a kiosk.”

Ascherman pushed against this argument, though, believing that McDonald’s and other corporations have money to spare.

“I find that the C.E.O.’s have just made less money in other instances where minimum wage has been increased,” he said. “McDonald’s C.E.O.’s can afford it. They paid a $30 million stock bonus for all stockholders last year.”

Despite Ascherman’s argument, Flinn said that McDonalds is not obligated to redistribute profits equally.

“McDonald’s is not a welfare organization, it’s a business,” he said.

Despite often being ignored, millions of minimum-wage workers like Kenya refuse to give up. Every day, Kenya gets up, goes to work and tries to get someone to listen.

“I just pray that somebody will help me,” she said.

In the past, it’s been easier to overlook the struggles of these workers, but now they refuse to go unnoticed. The movement has grown and pressure is building on both politicians and businesses to accommodate these workers.

However, $15 an hour isn’t going to accomplish the American Dream. Minimum-wage workers may be able to survive on $15 an hour but it’s unlikely that they’ll be able to thrive.