BY ROBERT HEIDE | When I first came to live on Christopher St. in the early ’60s after studying theater at Northwestern University in Illinois, I was happy and content to find myself in the then gay mecca and bohemian enclave known as Greenwich Village.

Apartment rentals in those halcyon days were under $100; and there was a variety of cultural scenes to be involved in: folk music, coffeehouse theater, poetry readings in cafes, rock music at the Nite Owl and, of course, the gay bars. What was happening everywhere in the Village was certainly a big change from the small town of Irvington, N.J., where I grew up.

In college, I met a handsome crew-cut blonde theater major named Corky who made it his business to drag me to Chicago, and take me driving down Lakeshore Drive in a red Chevy convertible to the gay bars that were situated in that toddlin’ town’s “notorious” neighborhoods. As he introduced me to a group of his chatty and garrulous, good-looking drinking pals, I felt at once at ease and at home. Here fun, danger and adventure seemed to merge all together into one big ongoing party.

In the first bar we hit, which was named Louie Gage’s, Corky drifted toward the jukebox and, whispering into the ear of a muscular young Adonis, disappeared into a backroom. I wasn’t sure about what was happening that night; but I knew I was on my own.

Fascinated by this Midwestern gay scene, I eventually would take the elevated train from my college town of Evanston to Chicago’s downtown “Loop” and to the “near Northside,” where I came into contact with others who were on the prowl looking for love, lust and some kind of undefined new freedom not available back in the old hometowns.

For me it was an exciting time of endless encounters, and new discoveries. I entered into a quest then that was the beginning of a search for my own particular gay identity. Acting in plays at Northwestern, I was first cast in the role of Snobby Price in “Major Barbara,” and then as the confused “homosexual” young man who is “saved” by an older woman in the play “Tea and Sympathy.” (Deborah Kerr and John Kerr [no relation] played these parts on Broadway.)

After college, I headed back East to New Jersey for a time but wound up renting an apartment with the financial help of my father on Christopher St., where I still live today. In the early years of the ’60s there was no such thing as gay politics. It wasn’t until late June 1969 that the riots at the Stonewall Tavern occurred, which led first to Gay Pride and then to Gay Power.

In the decade preceding those riots, it didn’t take me long to discover that Christopher St. at Sheridan Square was the cruisiest gay pickup spot in town. My apartment was a block away from the 10th St. bar (between W. Fourth St. and Seventh Ave. South) that was the gathering place of the most popular gay crowd in the Village — a cellar dive called Lenny’s Hideaway (now Smalls jazz club).

A pal first described Lenny’s to me as “a homosexual hot spot” and that was all I had to hear. Down in the depths of “The Hideaway” there was a lively bar attended by an exotic Russian ballet dancer named Robby who served bottled beer (no glasses, please!) and a drink called a “Klinker,” which was a lethal mix of apricot brandy and vodka combined with a cheap house brandy. Drinking this concoction in a brass cup made for a real quick high; and after a few of these, some people wound up passed out on the floor. Lenny the mobster proprietor would then haul them upstairs, dumping them onto the sidewalk.

Lenny’s mainly attracted intellectual and creative gay types, including actors, artists, musicians and writers, who lived in the Village and were out to make a name for themselves — as it turned out, many of them did.

I first met Edward Albee there with his live-in partner-companion-lover of many years, William Flanagan, a music critic for the New York Herald Tribune. Also a composer, Flanagan and another of Lenny’s regulars, Ned Rorem, were both protégé’s of Virgil Thomson.

To my surprise, one night my college buddy Corky Corcoran turned up in Lenny’s. He told me he had moved to New York and had become a theatrical agent. Heavy drinking was the order of the day at this in-the-cellar establishment, and many of those I met never left the premises until 4 a.m. After that hour, some would be invited to continue the party at a nearby Village pad. Fueled by booze, the happy-go-lucky gay crowd was mainly there on the make looking for a one-night-stand bedtime partner.

At the bar or at the big brightly lit Wurlitzer blaring out show tunes of the day sung by Mary Martin or Ethel Merman, you could connect with men who were on the prowl and out for a good time. Uptown female luminaries, often referred to as “fag hags” by the clientele, included the likes of Tallulah Bankhead and Peggy Hopkins Joyce. They would drop by to check out the downtown gay scene, sit at a table in an arched enclave and have a cocktail.

In his first play, “The Zoo Story,” Edward Albee describes the “fairies in the bushes” in Washington Square. If you were in a relationship, you would be asked if it was an “open one,” meaning — “do you sleep around?”

Others I met at Lenny’s in its heyday were Broadway luminaries Tom “Dreamgirls” Eyen and Jerry “Hello Dolly” Herman, as well as the poet Richard Howard.

A famous Village character who patronized the place was Ian Orlando MacBeth, who it was said was related to the designer Cecil Beaton. He dressed in Shakespearean garb, spoke in iambic pentameter and caused a stir by sporting a live squawking parrot perched on his shoulder.

A tall, blond, good-looking Christie Barter, a top editor at Cue magazine, held court there almost every night of the week. The striking, neurotic and intense Ron Link, later the director of several Off Broadway shows starring Divine, was also a regular. Making a glamorous nightly entrance down the stairs to the crowded barroom at that time, always dressed in all black, was H. M. “Harry” Koutoukas, who was known later as the “quintessential Cino playwright.”

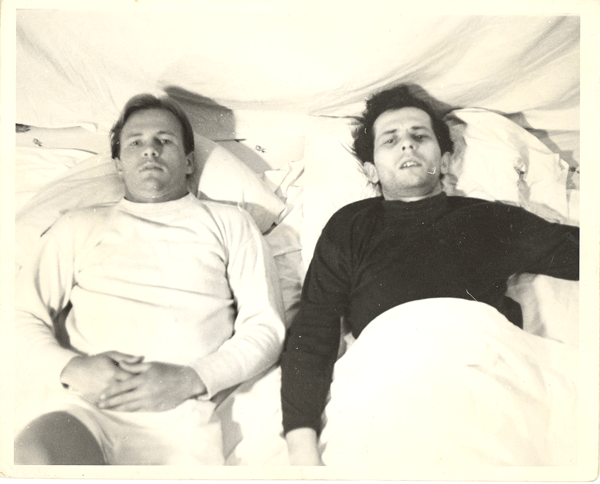

In 1965, I myself took up pen and wrote a play called “The Bed” for the Caffe Cino about two men in a time warp who were drugging, drinking and could not make it out of bed for days or weeks at a time.

In the mid-’60s the flamboyant Joe Cino ordered some of his playwrights to write plays about men, and among the first openly gay plays in town were Lanford Wilson’s “The Madness of Lady Bright,” Robert Patrick’s “The Haunted Host” and my play “The Bed,” which Andy Warhol turned into a film after he saw it at the Cino.

An earlier play I wrote for two men, one of whom is a down-and-out hustler, was presented Off Broadway by Lee Paton Nagrin at New Playwrights; I was told by an uptown critic that I should break my typewriter over my hands and never write again. This was in 1961.

The main gay bars on the circuit after Lenny’s in the ’60s were the historic Julius’, which is still thriving on the corner of 10th St. and Waverly Place; Mary’s and the Old Colony, on Eighth St.; and the San Remo, at MacDougal and Bleecker Sts., which attracted an elite crowd. In the realm of gay hot spots one should not forget places like the Keller Bar, Peter Rabbit and other more tawdry Village watering holes.

The wildest scenes on the waterfront were in and around the parked trucks and on the rotting piers, where dangerous rough-trade sexual liaisons took place, with some gay men winding up being tossed in the river.

The Stonewall was perceived by uppity gays as a low-level, stay-away hustler hangout, but this was the place that in terms of gay history changed everything. I watched some of this fight for freedom with my lifetime companion, John Gilman, from Christopher Park as it happened in 1969. That led into gay liberation and the sexual revolution of the ’70s, and now — with the legalization of same-sex marriages — the Stonewall has been designated a historic landmark.