BY RICO BURNEY | New Yorkers will soon be paying more for public transit after the Metropolitan Transportation Authority voted last week to increase the price of unlimited MetroCards and eliminate bonuses on pay-per-ride MetroCards.

Under the new fare scheme, approved Feb. 27, the price of 30-day unlimited MetroCards will increase nearly 5 percent to $127. Meanwhile, seven-day unlimited cards’ price will be hiked by 3.1 percent to $33. The base fare will remain $2.75. But with riders no longer receiving a 5 percent bonus on refills of $5.50 or more, the changes effectively mean riders who do not get unlimited passes will be paying 5 percent more, as well.

Riders who qualify for reduced-fare MetroCards can expect to pay $63.50 for 30-day passes, $16.50 for seven-day passes and $1.35 per ride.

The fare hike will take effect April 21. The M.T.A. believes these fare hikes, as well those on the Long Island Railroad, Metro-North and M.T.A.-owned bridges and tunnels would bring in an extra $336 million every year.

The board was supposed to vote on raising fares last month but decided to table the vote until this month to explore other revenue-raising options. Some, such as City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, criticized M.T.A. leadership for effectively losing $30 million by delaying the fare hikes for a month.

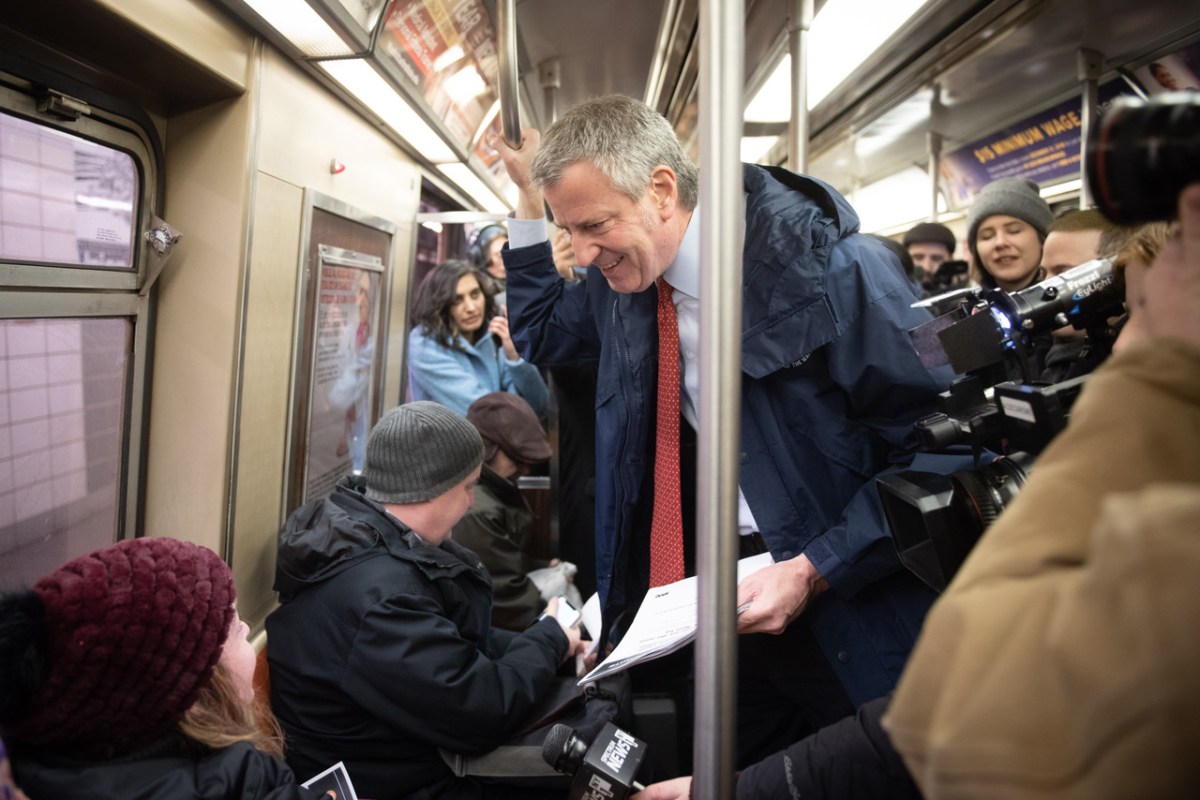

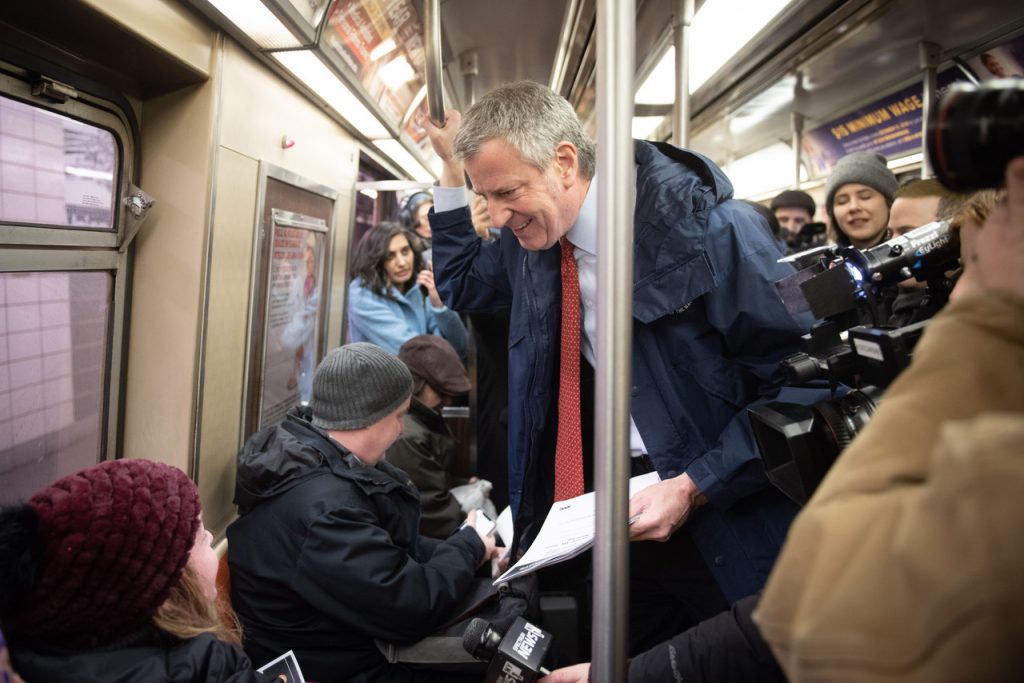

The fare-hike announcement came the day after Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio released a 10-point reform plan for the M.T.A. that would create new revenue streams to fund needed work to adequately run the beleaguered transit system.

Their proposal’s most notable aspect was a call for congestion pricing on all vehicles entering Manhattan below 61st St. The revenue raised from the tolls, as well as marijuana taxes would then be put in a “lockbox” to fund the M.T.A.

The governor and mayor have yet to say how much the new tolls would charge drivers, so it’s impossible to know exactly how much money their plan would add to the M.T.A.’s coffers. Cuomo previously said in his State of the State address he expects congestion pricing to raise $1 billion a year in revenue.

De Blasio, who for many years argued that congestion pricing would harm outer-borough residents, gave his support to the plan after getting assurance from Cuomo that low-income drivers and vehicles entering Manhattan at off-peak hours would be charged less.

The joint proposal also calls for fare increases to be limited to 2 percent per year to keep up with inflation and hoped-for cost-saving measures, such as consolidating positions under the six divisions the M.T.A. controls and independently auditing the authority’s assets and liabilities by next January.

Many transit advocacy groups that have long fought for congestion pricing as a way to reduce traffic and fund mass transit praised the often at-odds governor and mayor for working together to advance the idea.

“For New York City to be lifted out of its transit crisis, it is important for all members to work together toward finding a funding solution,” said a spokesperson for the N.Y.P.I.R.G. Straphangers Campaign in a statement. The campaign further characterized the announcement as “as signal to riders that both city and state leaders are committed to repairing and modernizing New York’s long-suffering transit system.”

Speaker Johnson also praised both Cuomo and de Blasio for working to pass congestion pricing. Nevertheless, he also said their joint statement “falls far short of the bold vision we need to address our city’s mass transit crisis.”

Specifically, Johnson disagrees with giving Albany more control over the city’s streets and transit system. The speaker has previously suggested bringing the New York City Transit Authority — the M.T.A. division that runs the city’s subways and busses — back under municipal control. He plans to say more about his alternative vision during his State of the City address on Tues., March 5, starting at noon.

While the fare increase is a done deal, much of the governor and mayor’s plan, on the other hand, still needs approval from the state Legislature. This may prove difficult considering that some suburban lawmakers have already stated they want some of the congestion-pricing revenue to benefit their constituents — and other legislators are not onboard with the plan, period.