BY OTIS KIDWELL BURGER | Scientists searching for extraterrestrial life look for moons or planets containing water because almost all of our life forms are composed of water (plus viruses, minerals, bacteria, etc.). Other life forms may be composed of something else, like liquid methane, but a Mork based on liquid methane would be a less-adorable alien.

Life was born in water. We still are, and still carry private oceans in us.

Prehistoric settlements also put water to practical uses. Recognizing that humans and their pets and livestock were large mammals needing a lot of water and producing lots of waste, they located villages when possible along waterways, which provided both water and convenient waste disposal. The Romans did manage both with elegant tall aqueducts and big sewers, and their water pipes were made of lead. … Did the empire fall to barbarians or to lead poisoning?

The Dark Ages that followed were not only dark but dirty. Streets were foul with garbage and excrement. “Gardez loo!” (“Watch out for the water!” from the French, “Gardez l’eau!”) householders would shout, emptying a slop jar or even a chamber pot above the unwary pedestrians below. In New York City in the late 1800s, thugs sometimes used this nasty habit — without the warning call — to attack and daze a victim, kill him, strip him and dispose of the body in the nearest alley or waterway.

Streams and waterways have continued to lead a complicated double life since prehistoric times.

In 1830, after an outbreak of cholera in London, Edward Chadwick “cleansed” the city by flushing all waste into the Thames, which was at the time the town’s source of drinking water.

In 1938, our family visited Polperro in Cornwall, England. The houses were built on the edges of a central stream, which channeled everything into the harbor and then the ocean. After meals, windows flew open, and — “scrape! scrape!” — the leftovers and garbage were donated to the river below. At high tide, some things would reappear in the harbor — grapefruit rinds, etc.

One morning, I came into the bathroom. My 10-year-old brother was leaning out the window, watching the end of a pipe that protruded from the house and over the stream. My little sister stood at the controls. “O.K., Emmy, flush away!” he shouted. She did. And yes, the toilets also emptied into the stream.

We children did not play on that waterfront but walked a long way to a sheltered beach to build sandcastles.

The drinking water, at least, came from farther upstream?

Not in all cases. An early photo of a Midwestern U.S. town shows two small boys with a bucket, collecting water from a city stream. Behind them, upstream, a hillside privy is emptying into that same stream.

In parts of India, there are quite impressive old brick-lined wells with stairways going down into them. But is the water clean? The Ganges is not only used for bathing and drinking, but for disposing of the dead. And in some parts of the world, collecting water entails a long day’s walk and the risk of also collecting cholera, typhoid, river blindness, malaria, etc. Or of being collected by crocodiles.

Free, safe, drinkable urban water is very recent and by no means universal.

The Great Plains in the middle of America, once covered by shallow seas, are now fairly waterless, often with desert and badlands. Nowadays, even the mighty Colorado is so dammed and diverted that it is nearly bled dry by towns and farms and scarcely reaches the Gulf of California. And its reservoirs are shrink-drying. The vast areas of central California, once the lush green “Salad Bowl,” irrigated by water from the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, are now dried and dusty…cut off from water because the snow packs in the Sierra Nevada that produced water are drying up.

The Western half of this country is suffering a decades-long drought.

The Eastern half is wetter but suffers pollution: rivers that catch fire, acid rain, coal ash, pig farms runoff, algae blooms from fertilizer runoff, zebra mussels and leaping Asian carp that can harm people.

Corporations wanted to introduce fracking into our water systems, poisoning millions of gallons of clean drinking water to extract undrinkable water and gas. But, thank God, Governor Cuomo has banned fracking in New York State.

Wars have been fought over water. They still are. Water is precious and necessary and growing scarcer.

The lives of Upstate farmers, vintners, cows, cities — and New York City, too — depend on it.

When the Dutch settled here, Manhattan was a well-wooded island, with many freshwater streams and springs.

Drinking water was provided by private wells and springs. The first public well was dug in front of the old fort on Bowling Green in 1677. In 1775, a reservoir was built on Broadway between Pearl and White Sts. The Collect, a large freshwater pond, was tapped by wells. Water was conveyed by hollow logs, then wooden pipes and later, cast-iron pipes. The population kept growing. More local reservoirs were built. In 1830, a tank for fire protection was installed on 13th St. (Fires often devastated the city.)

Garbage was cleaned by the rivers and by roving pigs. Backyards housed outhouses, which were cleaned out professionally, but in poor neighborhoods were apt to overflow in heavy rains. House manure was soon ankle deep on the streets.

My great-grandfather, William Henry Wilcox, was born in 1821 on Cedar St. in Lower Manhattan. His autobiography tactfully does not discuss outhouses, slop jars, chamber pots and other household waste-disposal arrangements, but he does describe the other uses of water.

My house on Bethune St. was built in 1836 and has been much modified. Most of the working parts of the backyard have long since disappeared. But his yard once had an “airy” near the kitchen, and a room above it, and an arched brick-lined vault under the garden that kept perishables cool and flooded every spring from an underground spring. Washtubs were kept near the airy. A cistern stored rainwater running off the roof, and a bucket on a long stick with a crook hauled up the water, for washing and for washstand pitchers.

“We had no water pipes to freeze up and deluge the house,” my great-grandfather wrote. “Plumbers and their life-sucking bills had not yet begun to prey on the community. Water was drawn up from the cistern…and our drinking water was obtained from the street pumps. These were placed on the edge of the sidewalk every few hundred feet apart. Several times a day the servant would need to go and get a pail of water which would soon become unpalatable…especially in warm weather, when fresh and cool water was most desirable. As ice carts and ice delivery had not yet been thought of. Yet pump water was so far from pure that when the comparatively pure Croton water was produced, it seemed for a time almost undrinkable, so perverted had our taste become by the water to which we had become accustomed. After we had used the Croton water for a time, the pump water became absolutely offensive…so subjective to our habits do even our physical tastes become.”

So much for water.

As to the problem of waste! …

“The streets of the city were muddy and filthy in the extreme,” great-granddad wrote. “No provision was made for garbage except by throwing it into the street, where sooner or later it was found and devoured by hogs that roamed through all the residential parts of the city in great numbers with no one to molest them. They were recognized as the city’s scavengers, and many a poor Irishman (or woman) was practically encouraged to keep as many hogs as he could manage by the fact that it cost nothing to feed them. … I saw a man let loose his 30 hogs one evening, and was told that they all came home at night.”

In 1832 Asian cholera struck New York.

“The city was almost abandoned by such terrified citizens as were able to get away,” he wrote. “Grass was seen growing between the cobblestones on once busy streets… .”

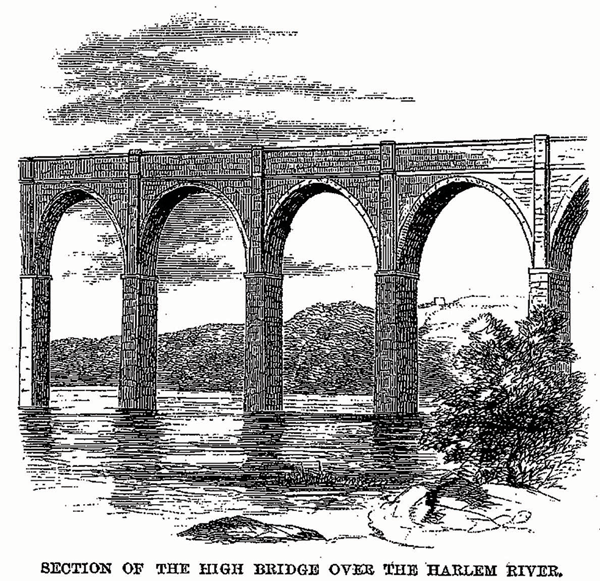

The dismal and often polluted water supply had often led to various illnesses. But after the Croton Aqueduct began to dispense clean drinking water from the Croton Reservoir, the city’s health improved. Water was brought from the Croton River in Westchester, and by aqueduct from the Croton Reservoir to the city, with reservoirs at 42nd St. and Central Park.

In 1836, the Wilcox family moved to Randall Place — Ninth St. west of Broadway — lined with tall brick houses on the south side of the street, and on the north side, a big sandy hill and distant occasional farms. And dense woods, in which my great-grandfather once got lost while out hunting.

About the same time, my husband’s great-grandfather sold his farm for $7,000 because being “out of town” was too lonely for his wife. The Plaza Hotel sits there today.

But the city kept growing rapidly. In 1905, the Catskill region was recognized as a suitable source of water, and reservoirs, such as the Ashokan, were developed. After legal battles between New York and New Jersey — over water from tributaries from the headwaters of the Delaware River — were resolved, more reservoirs, “managed” lakes, tunnels and controlled waterways were developed.

In 1951 when I was six months pregnant, my husband and I and our 2-year-old daughter scrambled down into a valley that had been scraped clean of houses, trees and fences and picnicked under one surviving tree. I swam in a busy little streamlet nearby while our daughter trotted anxiously along the bank.

The following year when we came back our picnic spot was covered by tons upon tons of beautiful clean cold water. A treasure! The Rondout, I think — or the Neversink? — reservoir was completed a little later.

These magnificent reservoirs and many others like them and “managed” lakes and waterways are connected by tunnels, and aqueducts can distribute water to any region suffering local drought. And New York boasts the cleanest and best-tasting water of any city in the world. Again — even though he hesitated — thanks to Governor Cuomo for finally banning fracking, which could well poison this system.

As to waste disposal, we are still following the prehistoric pattern — drinking water from upstream and (until recently) sewage still dumped downriver. In heavy rainstorms in New York City, raw sewage still overflows into the river from the combined sewer system, which becomes overcapacity at such times. But the Gansevoort Destructor — as the incinerator that once dumped ash as far as Bethune St. was known — closed long ago. Recycling and dog poop-scooping and trash barrels on every street corner have replaced hogs and horse manure. The city is far cleaner than it was in my great-grandfather’s day.

In addition to the oil and gas people, the bottled-water companies were also rumored to have been putting pressure on Cuomo to allow fracking. After all, what better way to sell clean drinking water than when the water supply has been poisoned with the chemicals used in fracking? And indeed I heard recently that Lake Cooper near Kingston, N.Y., may be turned over to the Niagara Bottling company, privatizing a public water supply.

And later that same evening in a grocery store I heard a recorded voice: “Why drink tap water? Visit our shelves full of safe, tasty bottled water.” Same water as in the watershed’s reservoirs, but bottled.

Oh, please! How about poisoning the air and then selling bottled oxygen?

Most of our other natural resources are for sale. But water for us is the stuff of life. And in many parts of this country, it is already rendered undrinkable by fracking.