[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

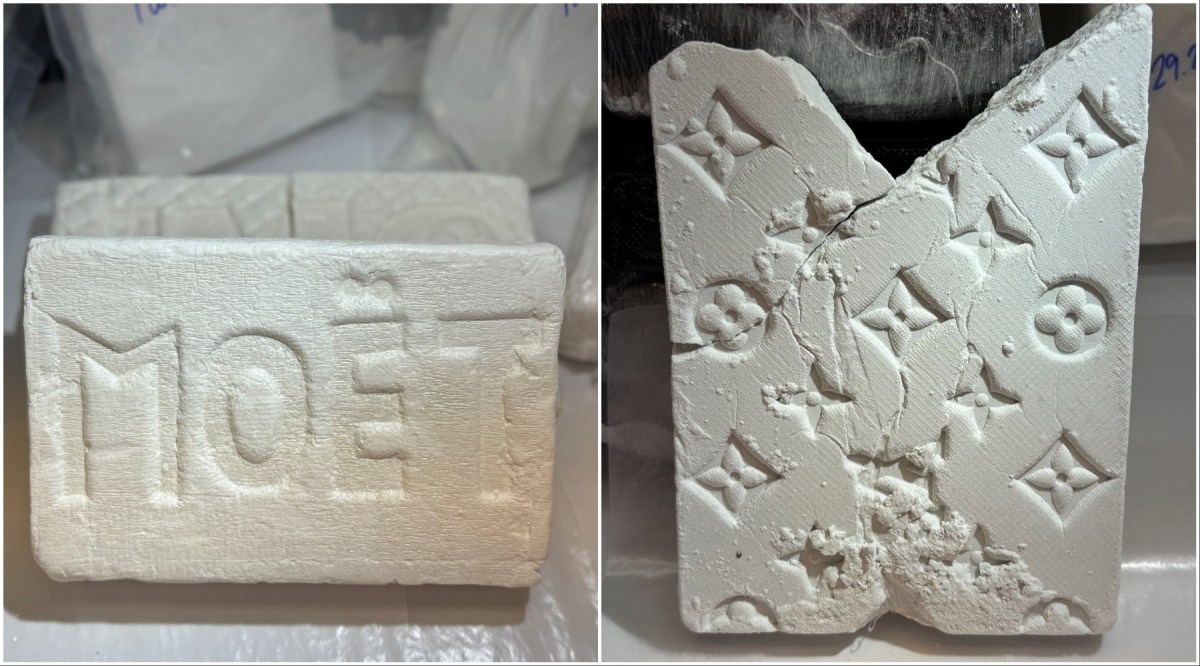

- Cleared for takeoff! Scout photographed on Memorial Day a few minutes before he took the leap into Washington Square airspace.

BY LORENZO LIGATO | Fledge day has come for the two red-tailed stars of New York University’s Bobst Library. Boo and Scout, the two baby hawks named after Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” have taken their first flight, after nearly 50 days of life.

And, now, a new journey is about to begin for them.

On Monday evening, May 28, Memorial Day, Scout, the firstborn of the two nestlings (or eyasses as they are formally known), left the 12th-floor nest overlooking Washington Square Park. It was around 8:05 p.m. when the juvenile hawk stretched his chocolate-brown wings and — after a quick glance right and then left — took a leap over the edge and briskly sailed away to an eighth-floor windowsill at N.Y.U’s Silver Center of Arts and Science, bordering the park’s eastern edge. Bobby and Rosie — the eyasses’ parents — were sitting several feet above on the same building, guarding the newly flying Scout. About 10 minutes later, Boo followed its sibling, landing successfully on the same ledge.

Hawk photographer D. Bruce Yolton — who blogs about red-tailed hawks and other wild birds in the city at urbanhawks.blogs.com — caught the event on his camera and called it “something almost unheard of.”

Double-fledges like this are indeed a rarity, agreed John A. Blakeman, a raptor biologist and master falconer from Huron, Ohio.

“Fledging red-tailed hawks seldom jump off in time so close to each other,” Blakeman observed, adding that, while later-hatching juveniles often do take less time to fledge than their older siblings, there is usually a time span of one day or longer between each bird’s fledging.

Second, Blakeman noted, fledglings rarely fly uniformly to an identical perch.

“The reason both birds flew to the new ledge almost surely derives from its previous use by the two parents as a prey cache — a site where captured rats and other prey had been brought for mutual feeding or consumption,” he explained. “In this case, the two eyasses flew right to where they had seen food being placed in previous days.”

The time of fledging, too, was atypical, since red-tailed hawks don’t fly at night. However, the reason for this other anomaly remains unknown.

The event, captured by the Hawk Cam installed at Bobst by The New York Times’s City Room blog in March, was greeted enthusiastically by hawk lovers in the city and across the world. Fans of Boo and Scout cheered and bid farewell and bon voyage to the two raptors on the chat room associated with the nest cam.

“There’s something so wonderful about new life taking hold among the parks and skyscrapers of a city I love,” said Hawk Cam devotee Carole Giangrande, a native New Yorker who is now living in Toronto. “I felt very protective of those birds. I loved their energy and I really felt a drive to see them ‘make it’.”

Giangrande added that the moment of fledging was hardly visible from the vantage point of the Hawk Cam, since the two eyasses wandered out of camera range.

“Someone did see a flash of wing, but it was so slight that they thought it might be a bug,” she noted. “I know this because I lurked in the chat room all evening.”

Meanwhile, for Boo and Scout, the real adventure has begun.

After spending the night together on the ledge at the Silver Center, the two hawks started to wander around the park, flapping their wings still somewhat ungracefully or resting on low branches and ledges.

Though the Hawk Cam is still up and running, it’s unlikely the two fledglings will fly back to their nursery at Bobst Library, Blakeman said.

Bobby and Rosie will continue to feed the two fledglings, at least until Boo and Scout have perfected their flight skills and learned to hunt successfully — which will most likely occur around eight weeks after fledging.

Yet, even under the vigilant supervision of Bobby and Rosie (and the watchful eyes of hundreds of hawk fans), the two baby red-tails will still face numerous dangers.

While more than 70 percent of all red-tailed chicks survive until fledging, the life-expectancy rates plunge after that, observed Glenn Phillips, executive director of NYC Audubon, an environmental organization for the protection of wild birds. More than a half of all fledglings, he said, perish during their first year of life, based on ID-band return data.

“The biggest danger is the fledging process itself,” Phillips noted. “The chicks have to learn how to fly and they are likely to end up on the ground or collide with a car.”

Yet, N.Y.U, the city’s Parks Department and its urban park rangers will be on alert to intervene if needed, Phillips said.

In addition, hawk fans have raised concerns over the danger of secondary poisoning from rats. The rodenticides commonly used in the city’s parks to control vermin are highly toxic to baby hawks and are responsible for several hawk deaths every year, said Phillips.

“That said, both N.Y.U. and the Department of Parks follow the guidelines to avoid use of rat poison during nesting season,” he added.

Philip Abramson, a Parks spokesperson, confirmed that the department stopped baiting for rats in the Washington Square Park area as soon as the hawk eggs hatched. Baiting won’t resume until the young hawks migrate to their own hunting territory, he added. Parks is employing alternative rat control measures, including prompt trash removal, covering any potential rat burrows and, soon, mechanical traps.

With a little help from N.Y.U. and Parks, hawk lovers can continue to enjoy the spectacle of nature unfolding itself, at least until midsummer. Then, Boo and Scout will be ready to leave their parents and Washington Square Park.

But for now, park users — be they fervid hawk watchers or casual visistors — can expect to see the two young raptors plunge down and hunt, or perch, just a few feet away.

“If that happens, just stand and watch. Don’t try to approach the nearby hawks or attempt to touch them,” falconer Blakeman said. “Few others get to see these regal birds so close at hand. It’s a wonderful spectacle in a wonderful city in a wonderful neighborhood.”