The MTA revealed a sweeping plan to save the subway system, including proposals that would rapidly increase the modernization of the signal system, improve wheelchair accessibility in stations and restructure the inner workings of the department.

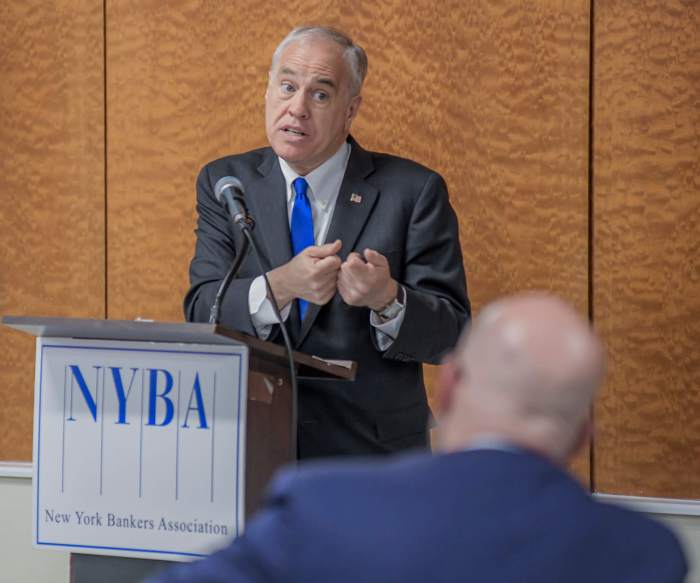

New York City Transit president Andy Byford unveiled the plan, called “Fast Forward,” at the authority’s board meeting Wednesday morning. After joining the MTA in January, Byford made it a priority to craft what he has called a “compelling, bold, imaginative” blueprint to transform a beleaguered subway system that has suffered significant drops in ridership amid a decline in reliability.

To address frequent service failures and capacity constraints in the subways, the “corporate plan” calls for extended service closures on nights and weekends in order to replace much of the system’s ancient signal system with a modern equivalent known as Communications-Based Train Control, or CBTC, within 10 years. That would be more than 30 years ahead of previous estimates, according to the report.

In the first five years of the plan, the MTA will aim to install the new signal technology on some of the most rider-heavy segments of five subway lines, including the Lexington Avenue, Eighth Avenue and Queens Boulevard lines.

The signal upgrades will also come along the F and G lines in the outer boroughs so that, in total, CBTC will be in operation for 3 million daily rides, a little more than half of a day’s subway ridership.

The MTA will continue CBTC installation in the following five years to encompass most of the system, so that roughly 5 million daily rides are served, with the upgrades coming to major segments of every line except for the J and Z.

The L train already operates with a CBTC system and the installation of similar technology on the 7 line is nearly complete, after significant delays in the project.

Experts and advocates believe the modernization would reduce the volume and impact of signal-related service outages while also allowing the MTA to run trains more closely together, reducing wait times and overcrowding.

“Riders have been asking for a serious and credible plan to fix the subway. This is that plan,” said John Raskin, the executive director of the Riders Alliance, who was briefed on elements of the plan. “Having reliable signals would be a game-changer for the quality of subway service. It would mean that we’re not a 21st century transportation system depending on 1930s technology.”

The biggest hurdle at the state-controlled MTA appears to be funding the plan. An official price tag has yet to be determined. “Costing of the Fast Forward Plan is under development,” the report says. The New York Times reported the plan could cost more than $19 billion.

The work and costs for the first five years will be included in the MTA’s next capital plan, which will outline major infrastructure projects between 2020 and 2024.

Byford’s plan also targets the system’s accessibility woes.

Only about one quarter of the authority’s 472 subway stations are compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The plan will, in part, double the current rate of ADA renovations at stations, with a goal of making 50 new stations fully accessible within five years. The authority will strategically pick which stations will be made accessible to ensure that riders are never more than two stops away from an accessible station.

To improve corporate culture, Byford also called for restructuring the framework of the MTA’s transit department, which oversees subway, bus and paratransit service, in order to reduce levels of management, create new departments and better facilitate upward mobility at the agency.

Sarah Kaufman, the assistant director for technology programming at the NYU Rudin Center for Transportation, hopes technology improvements go beyond just the signal system to include other amenities, like digital subway maps that can be tweaked to provide new service information.

“The signals plan is ambitious and will require significant funding and downtime of subway lines,” said Kaufman in an email. “It’s an opportunity for MTA and NYC to improve bus speeds and dabble in microtransit” — meaning ride-sharing services like Via, UberPool and Lyft Line — “to cover missed trips overnight. Subway stations shouldn’t just be accessible; they should be intelligent, able to inform riders en route where and when elevators are out, so riders can re-route as needed.”

City, state and federal governments all contribute funding toward the MTA’s capital plans. Raskin, of the Riders Alliance, said Gov. Andrew Cuomo and state lawmakers will have to lead on securing new money for the transit agency. He pointed to revenue from congestion pricing as one possible source for delivering sustained transit improvements.

“We will need Gov. Cuomo’s leadership and we will need legislators from all five boroughs and beyond to make this plan a reality,” Raskin said. “The MTA is doing its part by producing an honest assessment of what will be needed to fix the subway. Now, Cuomo needs to do his part to lead the way to a sustainable funding source that will make the MTA’s plan a reality.”

Dani Lever, a spokeswoman for Cuomo, said the governor has not yet seen the plan, but will review it.

“Our bottom line is that the plan needs to be expeditious and realistic and we made it clear to the chairman that before it is finalized, the MTA must bring in the top tech experts in the nation because if we can experiment with self-driving vehicles, there must be an alternative technology for the subways,” Lever said in a statement.

Both Mayor Bill de Blasio and Cuomo had sparred over funding the current, $32 billion capital plan.

More recently, the two squabbled over the comparatively small amount of money needed for the MTA’s $836 million Subway Action Plan, a short-term strategy for subway improvements.

Eric Phillips, a spokesman for the mayor, said the MTA should use its existing resources and suggested the state should approve a new revenue source, such as de Blasio’s millionaire’s tax, to help fund the plan.

“While the devil is always in the details, early reports suggest that the MTA is finally focusing on the infrastructure riders need to get around,” Phillips said in a statement. “If that turns out to be true, that’s progress.”

‘Fast Forward’ Transit Plan by Nicholas Loffredo on Scribd