Some are born to adorn the silence. Others arrive to split it open.

Alice Neel belonged to the latter. Her brush did not trace ornament—it carved into the marrow. Each stroke summoned something raw, something restless, something not meant for polite conversation or polite walls. These were not portraits. They were confessions rendered in flesh, interrogations dressed in oil, unsent love letters to the fractured American soul.

Nothing about her work asked for approval. It demanded recognition. It dared the viewer to hold its gaze and not look away.

Born in 1900 under the Puritan thumb of Pennsylvania, Neel tore herself from the suffocating domesticity prescribed to women of her class and generation. At the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, she developed not a penchant for pastoral pleasantries, but a ferocious eye for emotional truth. Upon entering the art world, she found herself swimming upstream against a current of masculine bravado. While Pollock hurled his demons in paint and Rothko murmured abstractions of the void, Neel remained defiantly figurative, rooted in the flesh-and-blood reality of human existence. The gatekeepers of high modernism turned away from her, and she painted anyway.

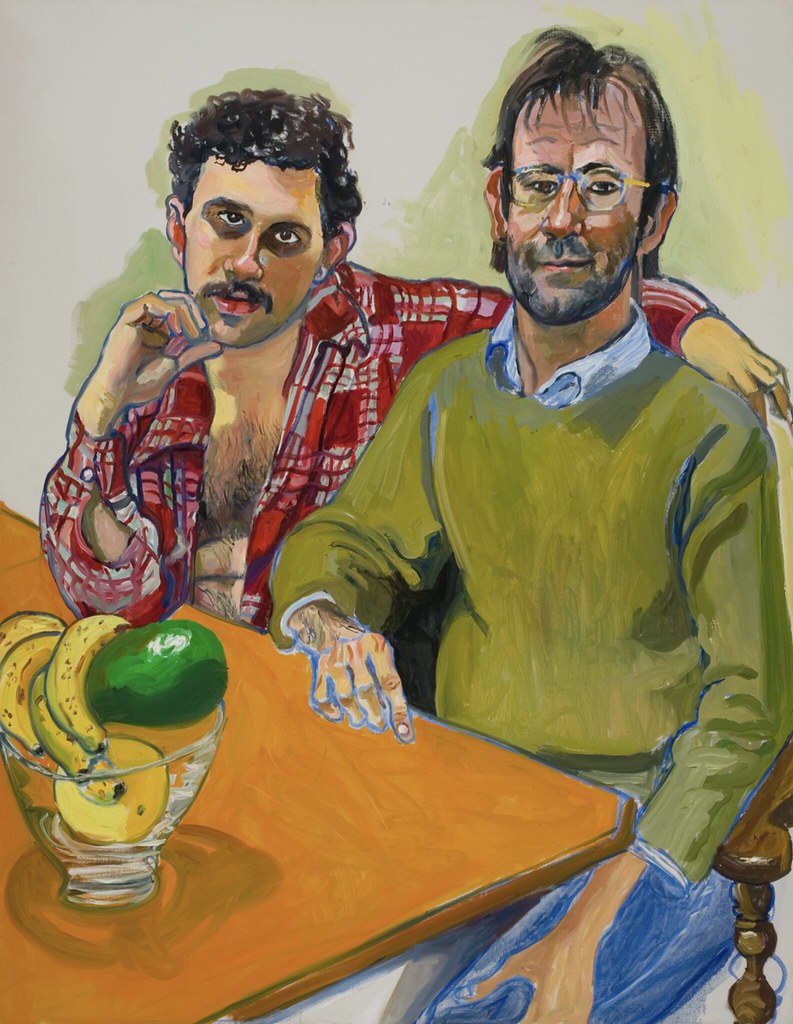

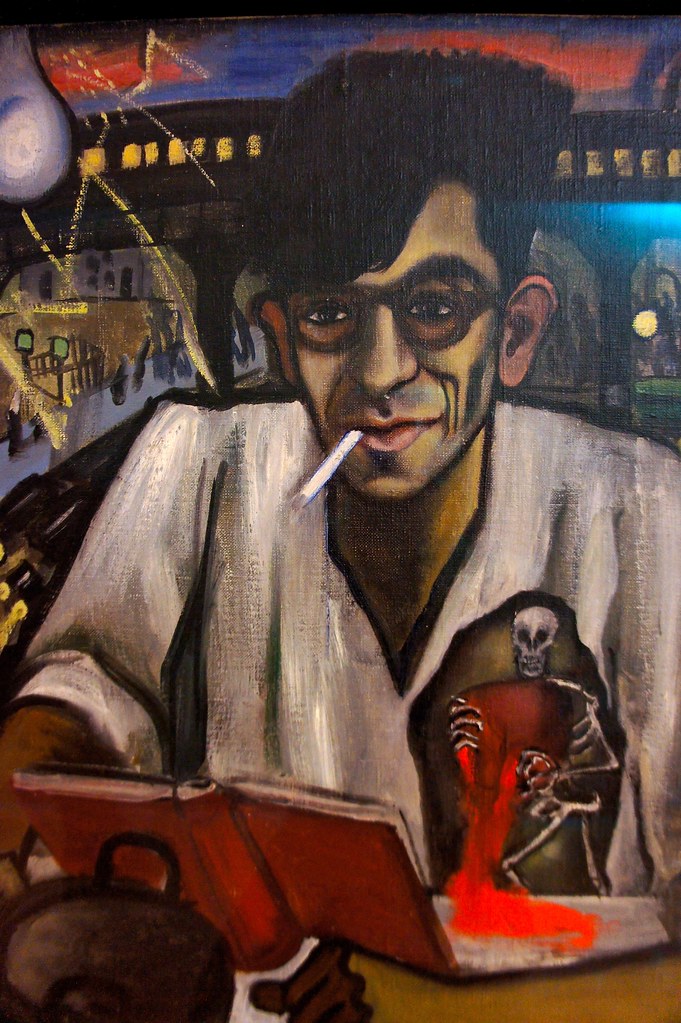

Exile, for Neel, became a kind of artistic haven. Within the crumbling walls of her Spanish Harlem apartment, she turned her gaze toward those society ignored—immigrants, organizers, intellectuals, pregnant women, queer lovers, disheveled children, and the exhausted machinery of everyday life. These were not idealized muses. They were subjects in the truest sense—alive, imperfect, and brimming with psychological density. Her portraits captured not the performance of identity, but its fragile architecture.

She painted with a palette of confrontation: acid greens, jaundiced yellows, bruised violets. Every figure bore the mark of a lived life. Clothes sagged, bodies slouched, genitals were left unhidden. She chronicled motherhood with the same unflinching eye—babies limp with sleep, toddlers mid-tantrum, the dark rings under her own eyes etched as clearly as the baby’s curls. Neel refused to idealize. Her realism was not academic. It was insurgent.

Personal tragedy threaded through her life with surgical precision. She lost a daughter to diphtheria and another to custody battles. One of her lovers died by suicide. Institutions tried to swallow her whole, yet she emerged with her vision intact. Even in old age, she refused to conform. At eighty, she painted herself nude, cane in hand, belly soft and sagging, eyes glinting with defiance. The portrait was not about aging gracefully. It was about aging truthfully.

Feminism did not create Alice Neel. It simply rediscovered her. In the 1970s, second-wave feminists embraced her as a mother of visual rebellion. Recognition finally arrived, decades after it should have. Still, she remained uncategorized—too radical for conservatism, too honest for idealism, and too individual to be reduced to a single movement. Her work stood alone, equal parts wound and testimony.

Her portraits now reside in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum, and the Tate Modern. Despite these posthumous accolades, her legacy cannot be contained by canvas or institution. It reverberates in every raw portrayal of the body that refuses to conform. It lives in every honest depiction of motherhood, illness, class, rage, and desire.

Alice Neel did not simply paint the figure. She painted the invisible war between being seen and being known. Her work exists as both mirror and reckoning, reminding us that art, at its highest calling, does not soothe. It awakens.

For more dispatches on art, femininity, and subversive brilliance, visit AvalonAshley.com— Where power dresses in red lipstick and tells the truth with a sharpened brush