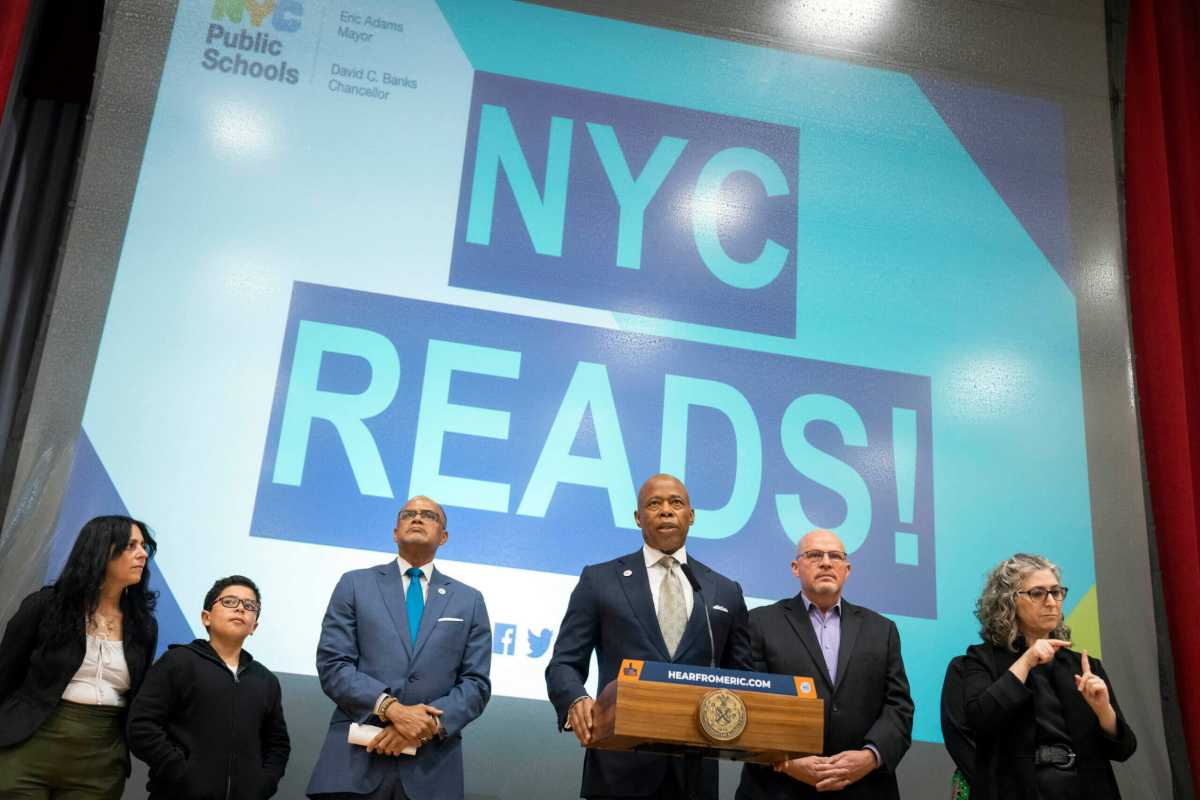

Big changes are coming to New York City public schools this September to help students learn and love to read, Mayor Eric Adams and Schools Chancellor David Banks announced Tuesday.

Hizzoner and the chancellor unveiled the “NYC Reads” campaign, a single and universal curriculum in early childhood programs through the fifth grade and include staff training and support. Adams and Banks stated that literacy is the city’s “core focus and overriding priority of New York City’s public schools.”

Literacy and reading comprehension is the number one priority for New York City’s public school students, both Adams and Banks said. They see the NYC Reads program as an effort to strengthen student literacy and reading instruction in the city’s elementary schools and early childhood programs — with the goals of reversing declining reading levels, and having every student reading at their appropriate grade level by the third grade.

“Today we are announcing NYC Reads, a literacy campaign that will ensure our classroom instruction is rooted in the science of reading and gives our students the foundational skills they need to become confident readers,” Adams said.

State assessment exams have consistently shown declining and poor reading levels across New York City students. Currently, more than half of New York City’s third through eighth grade public school students have inadequate reading skills and comprehension. Banks had earlier highlighted the racial disparities with Black and brown students at a city council education budget hearing in March.

“Nearly two-thirds of our Black and Latino students are not proficient on the state English-language arts exams,” Banks had said. “We’re going back to basics by strengthening phonics instruction. We’re doing early literacy screenings for our students, making sure we identify any barriers.”

Roughly $35 million will be invested next year into training and coaching for teachers and leaders to successfully get the curriculum into their classrooms.

Adams called the campaign a “historic curriculum shift” that the nation’s largest school district deserves.

“We owe it to our young people,” Adams said. “We owe it to our educators who have been working hard to teach without access to the right tools.”

“Teaching children to be confident readers is job number one,” Banks affirmed.

What the curriculum will look like

Starting in the 2023-24 school year this September, the city will roll out the NYC Reads campaign in two parts. The first half will include the adoption of “The Creative Curriculum” by all early childhood education programs in New York City.

The curriculum will emphasize phonetic awareness, which emphasizes hearing the sounds of words, and phonics, which stresses being able to match sounds to letters.

“Oftentimes, we don’t talk a lot about the importance of early childhood education in reading,” Banks said at the campaign launch. “It starts at birth. It starts at kindergarten.”

Banks said that the Department of Education will ensure that students will have access to high-quality curriculum based on the “science of reading” and foundational literacy buildings blocks, such as phonetics, designed to help the earliest and youngest children.

“Before kids can learn to love to read, we first have to teach them how to read and the science of that,” Banks said. “We must give children the basic foundational skills of reading: teach them to sound out words, teach them to decode complex letter combinations, and build them into confident readers.”

Early childhood programs will also use “Teaching Strategies GOLD,” an authentic child assessment system, and “Ages & Stages,” a developmental screener to inform the earning experiences that will be tailored to every student’s unique, individual needs.

Superintendents from 15 community school districts will then have the option to choose one of three curriculum to use for their elementary school students: “Into Reading,” “Wit & Wisdom,” or “EL Education.” Teachers will receive high-quality training before the start of the 2023-24 year and will receive additional coaching two to three times a month during the course of the school year.

In the second phase, the remaining 17 community school districts will purchase new curriculum materials in the fall of 2023 and spend the year preparing for full implementation in the 2024-25 school year.

For students with special needs, the curriculum material will be delivered to students with disabilities depending on their needs. The Special Education Office will “offer curricular support in key areas such as pacing and prioritizing, building knowledge through various experiences and modalities, ensuring access to educational technologies, providing writing support, and identifying supplementary texts for practice and success.”

Banks pointed to the city’s largest and first-ever efforts to invest in students with dyslexia by providing specialized instruction and developing special education programs.

The city’s dyslexia pilot program, announced last spring, is currently in 160 elementary and middle schools with plans to expand, according to Jason Borges, the executive director of NYC Public Schools’ Literacy Collaborative. The program’s aim is to provide additional resources and training to support schools and screening for risk of dyslexia, and provide the appropriate interventions for students at risk during the school day.

‘We need to go back to basics’

City Council Member Rita Joseph, who chairs the City Council’s education committee earlier pointed out that the city prioritized the wrong methods of teaching literacy to students.

“We abandoned reading because we were being fancy,” Joseph said. “We need to go back to the basics.”

Joanna Cohen, principal of P.S. 107 John W. Kimball in Brooklyn’s District 15, shared her experience initially transferring her graduate school knowledge to her students, but seeing very little success despite a “balanced literacy approach.” She then switched course and introduced phonetics instruction into her classroom.

“I implemented it as best as I knew how,” Cohen said at the campaign launch. “I saw my struggling readers make some progress that year.”

Her students’ literacy improvements became even more visible after she started teaching English to language-learner students and recently-arrived migrant students.

“I was blown away by how quickly they became fluent English speakers, readers, and writers,” Cohen said.

Still, there were insurmountable challenges Cohen faced in implementing literacy instruction on a wider scale. Without broad support from the system and the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cohen saw her efforts drop by the wayside.

“School-wide change and literacy proved difficult, particularly without the support of the larger system,” Cohen said.

She acknowledged the city’s NYC Reads campaign as finally addressing a deep-rooted issue she had long dealt with.

“What I felt in my gut for many years, we all now know: that we have been working with the wrong playbook for teaching children to read for far too many years,” Cohen said. “I know that structured literacy will be exactly the kind of teaching our struggling students need and it will also take our high performers farther than we ever dreamed they could go.”

Assemblyman Robert Carroll (AD-44), a staunch advocate of student literacy and reading, approached Cohen last October to discuss if Cohen’s school would consider becoming a “structured literacy pilot school.” Supported by a grant from Carroll, Cohen decided to adopt the proposed model and reported early success from it.

“Structured sequential literacy works best for all students, not just students with phonological awareness issues or dyslexia,” Carroll said.

Carroll said he was lucky someone at his public school in Brooklyn noticed his struggles with reading, and that if they hadn’t been properly addressed, he wouldn’t be where he was today.

“If I had not been, I would not be sitting here today,” Carroll said. “I struggled with dyslexia as a child. The reason I care about it is because my life was almost destroyed”

While Carroll said he commended the state for spending the most in the nation per pupil, he said he could not stand by the state’s current ranking as 45th in the nation in reading scores. New York state is currently ranked as the seventh most illiterate state in the nation.

Adams referenced the number of Rikers detainees who have dyslexia or are lacking a complete high school education. Currently, 70% of incarcerated adults read below a fourth-grade level, according to the National Adult Literacy Survey.

“When you’re watching the dismantling of communities, you will see the lack of how we are educating our children,” Adams said. “We looked at that when we started to see young people who were participating in criminal behavior at a young age. It was just this pattern that went back to education.”

Banks presented data at the campaign launch breaking down the racial disparities of literacy across New York City’s public school students. Currently, 30% of Asian American and Pacific Islander students, 33% of white students, 63% of Latino/Hispanic students, and 64% of Black students, are not performing well in literacy.

“You’ll see that it’s even more profound for kids of color,” Banks said.

They weren’t picking up literacy skills because the city has been providing its schools and educators for the last 25 years with what Banks called “a long and complicated flawed playbook with overlapping, contradictory and sometimes just flat-out bad guidance.” Now, the city will completely overhaul its current playbook, and instead scrap the “balanced literacy” program for the 1-2-3 basics of phonics and phonetics.

“It is a very comprehensive approach, but phonics and phonetic awareness has been missing in far too many of our schools,” Banks said. “We’re going to fix that.”

Read More: NYC Charter Schools Show Strong Academic Performance Stats