Hank Willis Thomas knows how to hold a paradox in his arms and make it shine.

Jack Shainman Gallery’s newly opened Tribeca flagship presents I AM MANY, Thomas’ eighth exhibition with the gallery, bringing together large-scale sculptures; retroreflective, lenticular, and textile works; and a group of mixed-media assemblages.

Across these forms, Thomas continues his investigation into the myriad ways the past and present remain interwoven—how legacies of exploitation and oppression echo alongside emergent architectures of community and solidarity. The show is less a chronology than a living circuit: images and gestures feeding one another, charging the room.

Last Friday, before sculpture or slogan, there was a soundless flash in my chest—the kind that retroreflects history back at you and leaves no place to hide. The room was still, and yet my body started shaking loose what it had stored: the slow bruise of inheritance, the tug-of-war between overcoming and regression, the ache that arrives when you realize the wound is older than you are and somehow still warm.

For over two decades, Thomas has built a conceptual language fluent in photography, sculpture, screen printing, installation, and video. He does not merely cite the archive; he metabolizes it.

Iconic photographs of protest and resistance—those indelible, over-reproduced images that risk calcifying into textbook wallpaper—become oxygen in his practice, refitted for the present tense. What unites the work is his insistence on the multivalence of history, the way meaning refracts depending on who is looking, when, and under what light. History is not a closed case file. It is an active site.

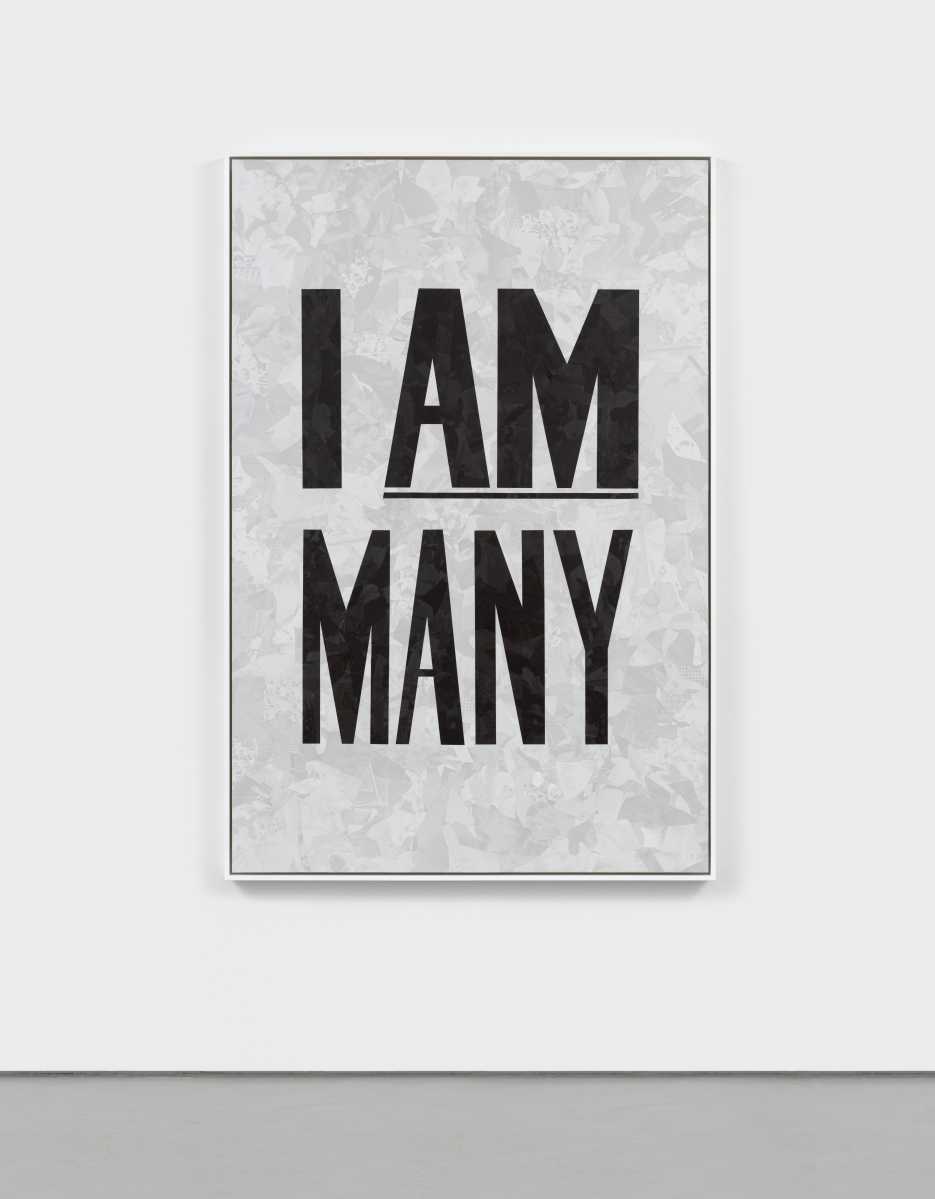

The exhibition’s title work takes its charge from the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike—the rallying cry “I AM A MAN,” uniform and thunderous, marching across the years with a typographic steadiness that still rattles the ribs. Thomas extends the phrase into new iterations, not to dilute it but to widen its field, and he renders portions in retroreflective vinyl.

Under the soft wash of the gallery lights, the works read one way; under flash, they bloom, revealing latent images of protest that had been hiding in plain sight. It is a brilliant formal conceit and a moral one. Truth—especially the truth of Black life in America—has too often required an additional flare to be seen: a camcorder, a cell phone, a witness who refuses to look away.

Thomas makes us complicit in that act of seeing. He asks us to lift the camera, to activate the surface, to bring the submerged to the surface again.

That demand ripples through Black Survival Guide, or How to Live Through a Police Riot (2018), originally commissioned by the Delaware Art Museum. Thomas sutures text from a historically practical manual—born of emergency and hard pragmatism—to contemporaneous photographs. The retroreflective material becomes a hinge between past and present, instruction and image, survival and remembrance.

With the flash, the hidden returns. Without it, we face the quiet distances that allow forgetting to happen. He offers us no comfort, only agency: resurrect, recover, remember.

The lenticular and textile works extend this choreography of visibility and concealment. As you shift your body, images slip, align, and reassert—like memory itself, never fixed in a single frame. The textiles, dense with history’s fingerprints, read like banners and scars at once: soft carriers of hard truths. In each medium, Thomas treats the surface as a threshold rather than a wall.

Sculpture remains a vital mode of public engagement for the artist. His punctum works borrow Roland Barthes’ notion of the photographic “punctum,” that piercing detail that leaps from the image and lodges in the viewer. But Thomas, ever the generous translator, shifts from the archival particular to the universal gesture.

In Community (2024), hands link with arms in a closed circle—a choreography of mutuality. The form is simple and, therefore, inexhaustible: strength as a circuit, love as structure, support as a repeating pattern. In E Pluribus Unum (2020), an eight-foot stainless-steel arm reaches skyward. The mirrored skin folds us into its surface; we become part of the object’s meaning just by approaching.

The sculpture is both a monument and a question: What does the collective look like when it reflects us back to ourselves?

As Jack Shainman notes, few artists interpret history in ways that actively clarify the present; Thomas does so with technical finesse and metaphoric depth. Exhibiting the work in Tribeca—a neighborhood that wears its own “beautiful but complicated” American history—reframes the visitor’s role. We are not passersby; we are participants, implicated and invited.

There is a narrow comfort available to those who treat protest images as artifacts. Thomas refuses that comfort. By literally embedding visibility into the surface—requiring the viewer’s flash to wake the specters—he dramatizes how memory functions in this country: never guaranteed, often conditional, always contested. He sharpens the dangerous romance of forgetting into a usable edge.

The works insist on attention without performing trauma for spectacle. They give us labor: the labor of looking, of acknowledging, of keeping the image alive in the present tense.

Something in that labor cracked me open. I thought about the long road from “I AM A MAN” to the fragile “we” we try to utter now. I thought about the cycle—how progress appears, luminous and near, then recedes, then returns again, wearing new clothes. I thought about the choreography of linked arms and the steady reach of the mirrored limb, about how a circle can be a sanctuary and an arm can be a beacon. I thought about how art can be both evidence and medicine, how it can hold grief without embalming it.

I AM MANY is not an elegy; it is a rehearsal for responsibility. If there is a prayer here, it sounds like this: Keep the image visible. Keep the circle unbroken. Keep reaching.

Run and see this exhibition — you will most certainly leave changed.

Jack Shainman Gallery Tribeca, 46 Lafayette St. For more information, visit jackshainman.com.