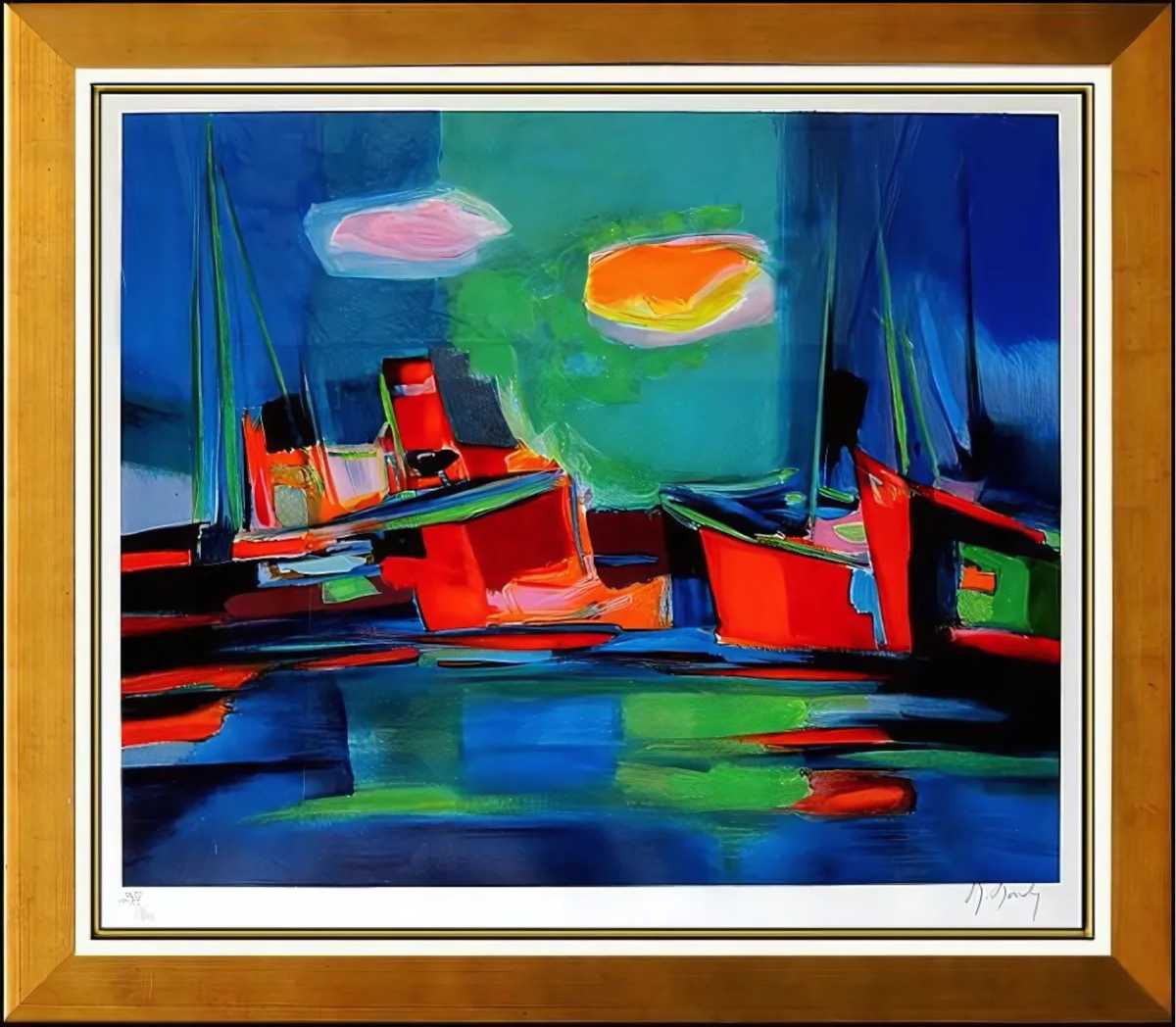

Marcel Mouly painted as if color were oxygen—necessary, inexhaustible, life-giving. Paris formed him, war tested him, and modernism gave him a rigorous grammar to bend toward lyricism.

He apprenticed himself to the great conversation between Matisse’s chromatic boldness and Cubism’s architectural intelligence, then answered in a voice unmistakably his own: interiors and ports that hum like chamber music, still lifes that feel as inevitable as weather, lithographs that carry the swing and clarity of a bell.

History did not spare him. Imprisoned during the Occupation, he emerged with an almost ascetic devotion to making, studying in the orbit of Jacques Lipchitz and absorbing the cubist discipline of form before flooding those planes with saturated, singing color. The result was not fusion for its own sake, but an elegant tension—structure steadying rapture. Even in the most static subjects, Mouly’s surfaces keep time; geometry never stifles movement; chroma does the work of breath.

Few early markers announce a career with such confidence as Femme à la lampe (1946), acquired by the French state the following year and now in the Centre Pompidou. The painting feels like a thesis: figure and furnishing reduced to lucid volumes, edges tempered, light treated as pigment rather than illumination.

Where Cubism might fracture, Mouly sutures; where Fauvism might flare, he sustains a controlled blaze. The canvas declares a program he would refine for decades—interiors that are less rooms than resonant instruments tuned to color.

The achievement extends on paper. In the 1950s, Mouly embraced color lithography with a seriousness that treated the stone as a painter’s arena rather than a reproductive tool. Layer by layer—drawing, graining, inking, pulling—the image accrues like a chord built from separate notes, each pass altering timbre and light. Contemporary dealers and historians note how his lithographs rival his oils in authority, a claim underwritten by a long run of honors in the medium. The distinction is technical and philosophical: he shows that printmaking can be a primary act of invention, not a shadow cast by painting.

Mouly’s iconography reads like a catalogue of pleasures disciplined by design: carafes and tables, harbors and hulls, windows that behave like proscenium arches. Boats advance across tessellated seas; tabletops become stages for color to perform. One senses the School of Paris behind him, yet the works never feel derivative. He triangulates between Matisse’s warmth and Braque’s rhythm while keeping faith with his own temperament—a steadfast refusal of cynicism, an embrace of beauty not as evasion but as ethics.

Museums and ministries recognized the rigor early and often. State purchases in the late 1940s signaled official confidence; prizes and exhibitions accumulated as his language of lucid planes and saturated chords matured. The consistency across decades is striking. While the century lurched from crisis to crisis, his work stayed incandescent, as if insisting that civilization’s truest surplus is color arranged with intelligence.

To stand before a Mouly is to feel composure return. The compositions balance like well-set tables; the palette glows without shouting; the drawing remains calm even when the color surges. Technique here is hospitality: structure invites you in, color persuades you to stay. That grace is why private and public collections continue to court him, and why the work reads as modern rather than mere modernism.

For New Yorkers, the invitation is immediate. Mouly’s paintings and masterful lithographs are on view at Park West Gallery in Soho, where the rooms echo with that rare combination of rigor and radiance. Go for the color, stay for the equilibrium, and—if you are building a collection—claim a work that proves beauty can be serious, and seriousness can be beautiful.

See Marcel Mouly at Park West Gallery Soho; let the planes, the light, and the color do their quiet, indelible work