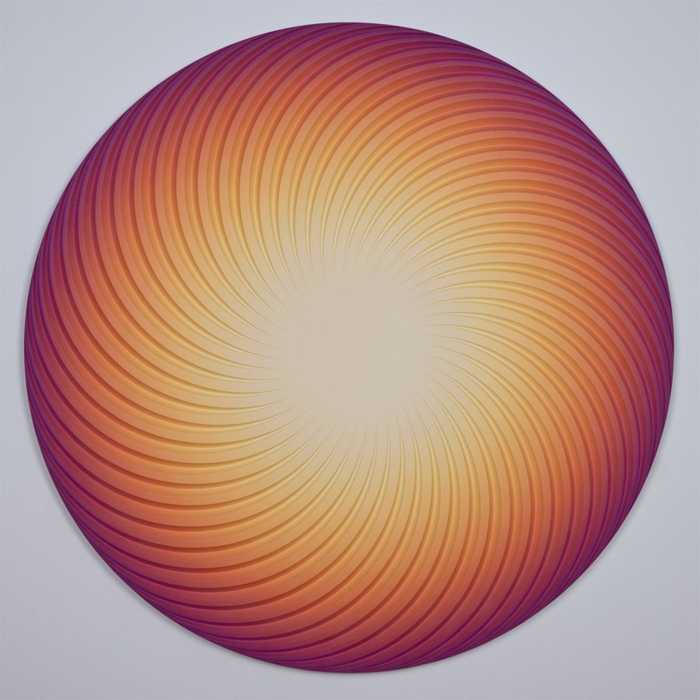

I met transcendence on a quiet afternoon in San Francisco. The room was hushed, the light merciful, and Mark Rothko’s No. 16, 1960 stood before me with the authority of an ancient oracle.

I did not glance; I surrendered. Minutes became an hour. The surface simmered and the edges breathed. Color began to hum like a tuning fork against the ribs. Stories rose without words, sound gathered without music, and memory—my own and somehow everyone’s—unfurled in slow, velvet ribbons. I left the museum in a state that no cocktail, conquest, or accolade has ever quite matched. Only magnificent art delivers that high, the kind that rearranges your molecules and leaves the air around you charged.

Rothko knew exactly what he was doing. Born Markus Rothkowitz in 1903 in what is now Daugavpils, Latvia, he emigrated to Portland, studied briefly at Yale, and found his way to New York’s crucible of modernism. Myth, tragedy, and the architecture of feeling obsessed him more than fashion ever could.

Early figurative work gave way to the “multiforms,” then to the mature floating rectangles that made his name. The Seagram Murals refusal, the gift to the Tate, the long descent into darker palettes, and the posthumous sanctum of the Rothko Chapel map a life that chased the sacred inside the secular. He insisted on canvases hung low and viewed close, not for gimmickry, but to collapse the distance between viewer and void. The gallery, for Rothko, was a chapel without doctrine.

His process was as rigorous as his metaphysics. Absorbent grounds, veils of thin color, glazes laid like breath upon breath, feathered edges that dissolve rather than declare—this is painting as atmosphere. The rectangles hover, not as hard geometry, but as weather systems of feeling. Pigment becomes a pulse; intervals between fields become time signatures. Stand close and the eye stops scanning for subject and begins registering temperature. The work does not describe emotion. It induces it, the way a key opens a lock that you did not know you carried.

That is why No. 16, 1960 felt alive. The canvas conducted me rather than merely depicting something to me. Color surged forward, then receded, a seduction without a single figurative cue. One moment grief; the next, a lucid joy so stark it almost embarrassed me.

The painting did not ask for interpretation. It demanded presence. I complied, and in return, it offered the oldest luxury we have: recognition.

Scholars love to place Rothko within Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, which is accurate and inadequate all at once. The category locates him; the experience exceeds it. Nietzsche and Greek tragedy, Shakespeare and the Bible, Frazer and Jung—these were companions to his studio practice. He pursued the sublime with monastic intensity, then stripped away every prop until only color and interval remained. The result is not minimalism of emotion, but maximalism of spirit. The fewer the elements, the louder the soul.

A crescendo happens if you let it. First, the eye adjusts to value shifts, then the body registers breath pacing to the painting’s tempo, and finally, the mind goes mercifully quiet. The field swells, heat collects at the edges, and you realize the painting has pulled you across a threshold. Pleasure arrives, not as a rush, but as a long, ascending note.

That is Rothko’s genius: an ascent you feel rather than analyze, a climax earned by attention.

Collecting, in this light, becomes something higher than acquisition. True collectors are archivists of human feeling. Value resides not only in provenance and market cadence, but in emotional precision—the artwork’s capacity to strike the same deep chord across years, addresses, and moods.

A collection that moves you is a living ledger of consciousness, a record of where humanity has been and a wager on where it might still go. Market value may fluctuate; the legacy of feeling does not.

Buy what alters your breathing. Live with work that recalibrates your interior weather. Choose the painting that refuses to leave your mind after you walk away, the one that calls you back like a promise. History remembers courage, and there is courage in collecting with the heart first and the spreadsheet second. The great works—Rothko’s among them—expand our capacity for awe. They do not decorate our rooms; they educate our senses and preserve our time.

I think of that hour in front of No. 16, 1960 as a vow. The vow is simple: honor the pieces that change you. Build a legacy that catalogs not just objects, but states of being. Treat your walls as an archive of human history written in color, frequency, and silence.

Rothko said he wished to express the basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom. He succeeded. The rest is our task: to feel, to remember, to collect with intention, and to pass forward a world where art remains the most sophisticated instrument we possess for knowing ourselves.

Where to see Rothko in NYC (quick list)

• MoMA — Core holdings; often on view.

• Whitney — Mid-century focus; intimate hangs.

• The Met — Modern & Contemporary Wing rotations.

• Guggenheim — Periodic showings within themed installs.

• Dia Beacon (day trip) — Cathedral-like scale and stillness.

More art essays, guides, and unapologetically luxe takes at avalonashley.com.