In a 4-3 split, the Court of Appeals ruled that mental anguish and PTSD a group of Metropolitan Transportation Authority workers and a teacher experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic was not “extraordinary” enough to warrant eligibility for workers’ compensation.

Writing for the majority, Judge Shirley Troutman said transit workers and teachers everywhere were experiencing the same stressful circumstances during the pandemic.

The high court’s ruling overturns the Appellate Division, Third Department’s finding last year in favor of the plaintiffs. Troutman also said the Third Department was wrong in considering workers’ pre-existing conditions when coming to its decision and that the high prevalence of COVID-19 in the workplace, which has been used to decide physical injury claims of infection in favor of workers, didn’t matter here, because the workers hadn’t established their stress was exceptionally different from their coworkers.

Troutman was joined in the majority by Judges Michael Garcia, Madeline Singas and Anthony Cannataro.

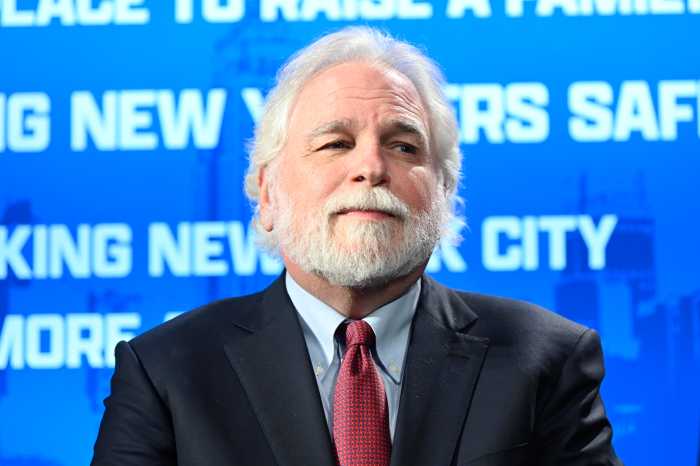

Geoffrey Schotter, the New York City-based attorney representing the four workers, said he believed the decision unfairly holds mental injuries to a higher standard of proof than physical ones. And, he said, the majority’s ruling may have repercussions for people with pre-existing conditions who seek workers’ compensation claims, and demonstrates a need for comprehensive legislation on mental health workers’ compensation.

“Our position has been that it’s the same ‘extraordinary’ standard, regardless of whether the injury is physical or mental,” Schotter said. “The majority in yesterday’s decision appears to have accepted…a higher kind of ‘extraordinary plus’ requirement for mental injuries. We think that is the wrong reading of what the law has always been.”

Schotter said he believed this was evident because the court didn’t consider the fact that COVID-19 was “prevalent” in the workplace as a valid reason for the workers to seek compensation for their mental injury, as prevalence of the virus has been considered valid reasoning for claims that a person was infected with COVID-19 at work, a physical injury claim.

“What the appellate division said is ‘If mental injuries are compensable to the same extent as physical injuries, if you work in a COVID-19 prevalent work environment, and you develop a mental injury as a result of that prevalence of being exposed, that needs to be compensable as an accident,” he continued. “I think the majority decision sidestepped the appellate division’s reasoning. They didn’t really address it head-on.”

While Schotter said he believed COVID-19 cases were generally moot at this point, as the pandemic has largely subsided, he believes this decision will impact future mental injury cases generally.

In her dissenting opinion, Associate Judge Caitlin J. Halligan, writing for the three-judge minority, centered on a disagreement with the majority’s “narrow” determination of what constitutes “extraordinary” stress, arguing the court should consider whether the stress workers experienced was greater than what was typically felt in a “normal work environment prior to the pandemic,” not only whether the employees seeking compensation were more stressed than other “similarly situated” employees at the time.

“The pandemic was certainly an extraordinary event,” Halligan writes. “The stress they encountered at work was categorically different from the countless differences and irritations to which all workers are occasionally subjected [because] this stress was grounded in real health risks.”

“When the extraordinary stress of working under conditions that involved ongoing exposure to a deadly disease caused these workers to develop serious psychological conditions, they turned to our century-old system of workers’ compensation,” her dissent continued. “Consistent with the purpose of the Workers’ Compensation Law, I would allow these claimants to pursue their claims for benefits.”

Chief Judge Rowan Wilson and Associate Judge Jenny Rivera joined Halligan in her dissent.

In an action Troutman, Halligan and Schotter all described as “unusual,” the Workers’ Compensation Board did not object to the dissenting opinion, which, if it had been the majority opinion, would have required compensation be awarded to the workers and reversed the board’s initial ruling.

“At argument, the board’s attorney encouraged this court to hold that stress from the risk of COVID-19 during the pandemic’s early stages could qualify as a compensable injury and emphasized that such a ruling would not ‘open the flood gates’ to a high volume of additional claims,” Halligan writes. “That position is unusual absent an acknowledgment that the board erred in denying recovery.”

Reached for comment, representatives for the Workers Compensation Board told amNew York Law that they do not weigh in on court rulings.

Regardless, Troutman said her majority opinion and Halligan’s dissent “could be expected to have a significant impact on the development of the law” — something Schotter said he disagreed with.

He said he believes new legislation is necessary, both to clearly ensure equity between mental injury claims and physical injury claims and because he found the court considering his clients’ pre-existing condition to be “immaterial,” concerning and potentially make it harder for those with similar conditions to obtain compensation.

Schotter said that’s because pre-existing conditions typically make it harder for workers to receive compensation for “occupational diseases,” or “nonaccident” injuries that are considered to arise from normal parts of the job (like developing lung cancer as a coal miner), and this ruling seems to suggest they also present a barrier to workers looking to obtain compensation for “accident” injuries resulting from experiencing stress “extraordinary” to them specifically because of their pre-existing condition (in this case, feeling additionally stressed about contracting COVID-19 because of a previous asthma diagnosis).

“This is a gross inequity,” Schotter said. “It creates a situation where you have a whole class of claimants who are excluded from recovering compensation for injuries and illnesses that are undisputedly work related, simply because they have pre-existing conditions that leave them vulnerable….The law needs to change so that once and for all, there is no longer any category of injury or illness that is undisputedly work related that is wholesale excluded from compensation, whether that’s because it’s mental and not physical, or because the claimant has a [pre-existing] condition.”

Current legislation, which passed after this case was filed and is therefore not being applied to the decision, holds that only workers claiming they developed PTSD and depression due to their working conditions don’t have to prove their stress was greater than their coworkers’ stress. Schotter said he believes this is “arbitrary” and will result in healthcare professionals diagnosing people with PTSD and depression who actually have a different mental disorder, such as anxiety, in order to ensure they are more likely to receive workers’ compensation.

That legislation, sponsored by state Sen. Jessica Ramos, passed this year. It is notably different from a bill she sponsored and was passed last year, which held that no worker would have to prove their stress was greater than their coworkers’ to successfully obtain compensation for any mental injury that occurred on the job.

First responders are the only class of worker “exempt” from the new law; they do not have to prove their stress was greater than their coworkers’ for any mental injury claims.

“This is completely arbitrary,” Schotter said. “I cannot, for the life of me, understand what’s different about PTSD and depression compared to anxiety. It seems like there was some political horse trading going on there that has nothing to do with science or medicine or any kind of rational reason why some mental health conditions are subject to [a different requirement] than others. That needs to be fixed.”

“The legislature should take up closing these gaps in compensability where it’s undisputed that a worker was injured by something on the job, and yet, for these arbitrary reasons they’re excluded from recovering that,” Schotter added. “Workers’ compensation is a compromise…where the worker gives up the right to sue the employer for negligence, and in return can file a workers compensation claim that’s supposed to provide easy and prompt compensation. These arbitrary exclusions…are really a betrayal of that bargain.”