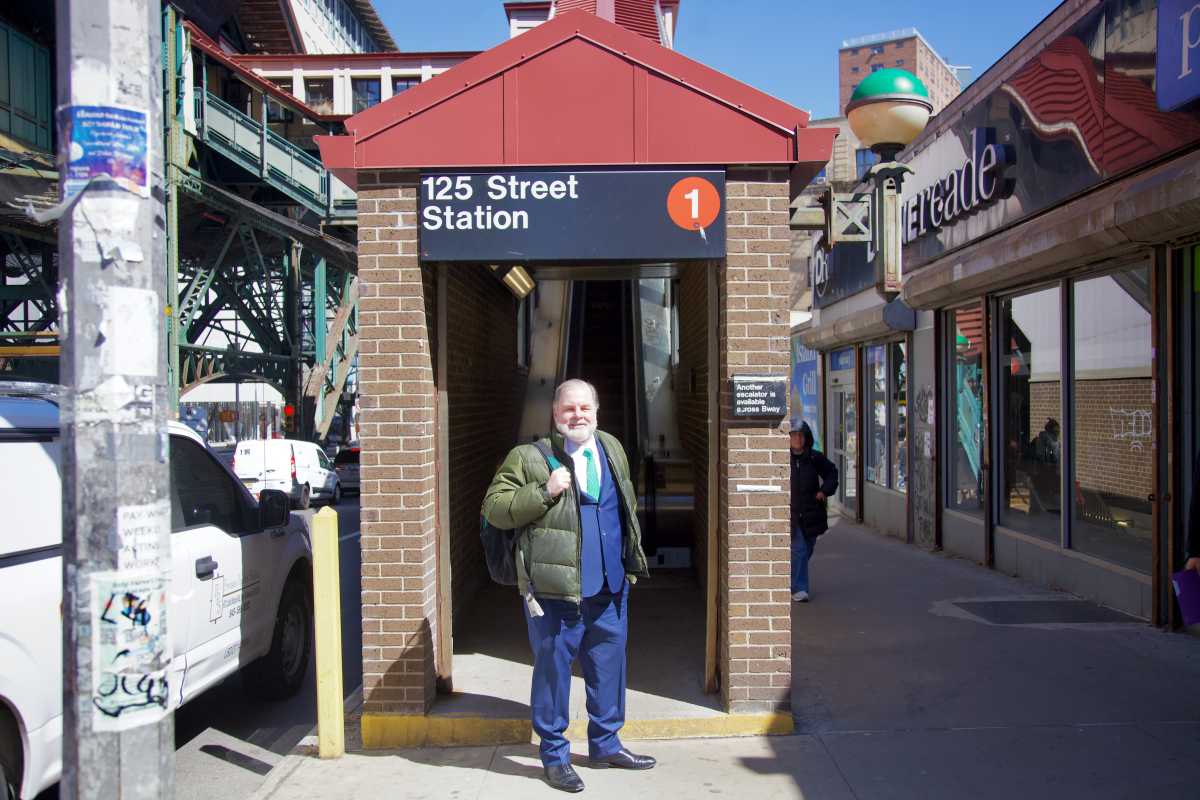

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s only challenger in the June Democratic primary has launched his campaign with a vow to tackle subway crime by aggressively prosecuting fare evaders.

When it comes to rising assaults on the subways in recent years, which research correlates with individuals with mental health disorders, Patrick Timmins believes the DA needs to hone in on “bullies and bad guys.”

“I kept looking around at what I’m seeing — I raised my kids here — and decided this is really a bad time in New York City in Manhattan for crime, for subway crime and street crime,” said Timmins, a civil litigator, former Bronx prosecutor and an adjunct law professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

He added later in the interview, “My position is let’s make our arrests…We can certainly do diversion. We can certainly look at some other situations, but either the subway…[is] free for everybody, or let’s take one last shot at trying to recoup some of that fare evasion.”

Where Bragg has declined to prosecute fare evasion as a standalone offense, Timmins wants to go after it as a deterrent. When Bragg first came into office he included fare evasion on a list of low level crimes he instructed his staff not to prosecute as part of a day one memo that became the target of a wave of blowback. In Timmins’ estimation, Bragg’s policy has resulted in the increases in subway assaults.

“Criminals are really smart. If they just went to school, they’d all be PhDs,” Timmins said. “They know how to read people. They know what’s going on around them. They speak to lawyers a lot.”

Though citywide data on subway violence shows that it’s rare per capita — felony assaults happen about once every 2.3 million rides — the rates have risen since the pandemic, and not abated the way shootings or homicides have in recent years.

Data complicates his assertion that those driving subway assaults are so-called career criminals. A report by Vital City found 80% of individuals in the top decile of overall subway arrests have documented mental health issues, and concluded that the nature of subway crime has fundamentally changed from what used to be calculated criminal activity to more spontaneous violence.

Timmins dismissed the findings as just a part of the picture. “That’s just reported stuff,” he said. “People who get their bag ripped off or a woman gets an elbow in the breast, they’re not going to report that. It’s always good to have statistics, always good to follow it to some degree. What’s down there is fear and tension.”

Other research focused on fare evasion prosecution draws mixed conclusions. A study from John Jay, Timmins’ own employer, concluded that from 2018 to 2023 more fare evasion across the city did not lead to significant changes in arrests for assaults and weapons possession. Other John Jay academics have argued that prosecuting fare evasion led to a significant crime drop in the early ‘90s.

Asked whether he was concerned that increased subway arrests could unfairly target predominantly communities of color, Timmins responded “I’m just concerned about Manhattan. Manhattanites are the people I’m concerned with. [There are] 151 subway stations, most of them are in decent neighborhoods.”

When amNY Law pointed out that Manhattan has many majority communities of color, Timmins didn’t directly address the concern of over policing, saying “my campaign is not just the fare evasion stuff. We can make that perfectly clear.”

Timmins got his start in politics working for former Bronx Democratic Assemblymember John Dearie before taking a position with the Bronx District Attorney’s Office in the mid to late ‘90s. He eventually joined a law firm as a civil litigator for retired union members and others diagnosed with cancer from exposure to asbestos, and began to teach as a part-time adjunct for John Jay.

Though his own resume doesn’t include high-level government administration, he didn’t hold back any criticism of Bragg’s management skills.

“There’s 1,700 employees, why in the world are you missing deadlines on the discovery?” Timmins asked. You need to manage these people so that we don’t miss any deadlines.”

On the issue of discovery, Bragg has joined Governor Kathy Hochul and other DA’s across the state in an effort to propose changing the 2019 discovery reform law that requires prosecutors to share evidence with defense lawyers on a speedier timeline or face the possible dismissal of the case. Timmins said he agreed with the idea of the reforms, which DAs across the state have complained have increased their level of case dismissals, but didn’t let Bragg off the hook.

Timmins has also criticized Bragg for his handling of two cases involving physical confrontations in which the accused were alleged to be defending themselves — as were the cases of bodega worker Jose Alba who fatally stabbed an attacker in his deli; and Brian Chin, a Chinatown landlord who allegedly fought back against a homeless man after he was attacked with a weapon. Bragg dropped the cases after initially charging both men.

Timmins suggested that the cases should have been vetted before Bragg brought charges. “I think we need to honor self-defense, study it, and understand it before arresting and indicting,” he said.

Timmins wavered when asked about the more high-profile prosecution of Daniel Penny in the chokehold death of Jordan Neely, which ended in an acquittal for criminally negligent homicide.

“I would say it was a toss up in terms of going forward,” he said.

Asked if he had concerns this approach could encourage vigilantes to take justice into their own hands, he said that he thought people would only pursue physical altercations as a last resort but “if you have to man up at times to protect yourself, you have to do that. So I don’t think vigilantes are gonna start popping up,” he said.

Despite Timmins’ promise to be tougher on crime, his platform also includes some ideas on rehabilitation, including the possibility of expunging the records of people who have served their time.

“These people who paid their debt to society, that’s American,” he said. “Let’s get them cleaned. My expungement motions will scrub the record so that if you pull a rap sheet, it’s never there.”