In a tribute to Black History Month, the Appellate Division, First Department on Monday evening presented a historical reenactment of the landmark Amistad legal proceedings.

Written by U.S Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Judge Denny Chin’s team, and narrated by the judge and his wife Kathy Hirata Chin, the program used historical legal documents to dramatize the events of the Amistad and shed light on how the case fit into the wider fight for the abolition of slavery and civil rights movement.

Presiding Justice Dianne Renwick of the state Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Department introduced the program.

“You’ve seen the Spielberg version; tonight you’ll experience the Chin version,” Renwick said, “which takes us through the legal proceedings that continued to the Supreme Court on the absurd question of whether the Amistad Africans were property or whether they were free people.”

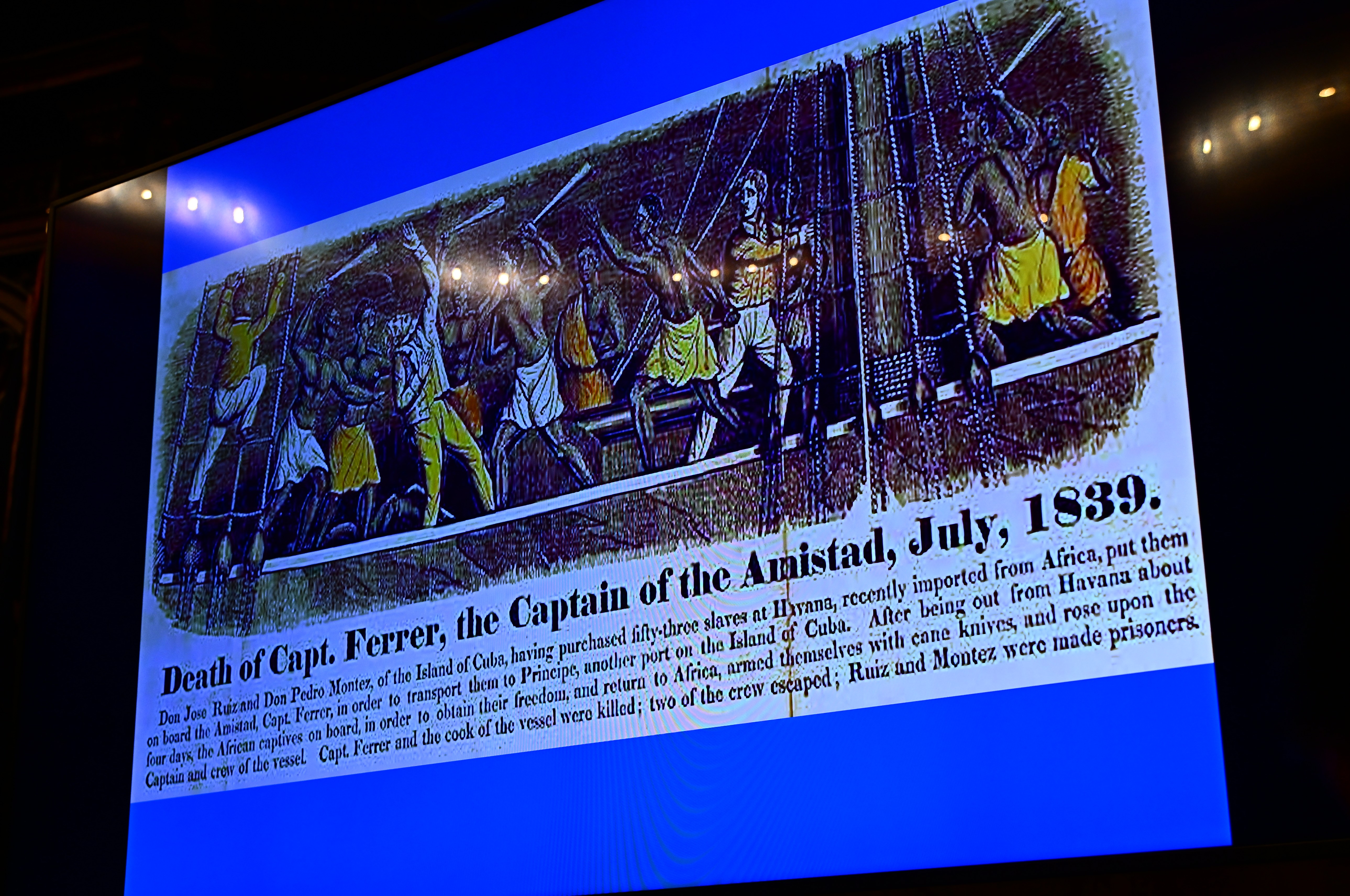

A cast of lawyers and judicial staff brought the Amistad narrative to life, beginning in 1839, when captives from Mendeland in present-day Sierra Leone were kidnapped and illegally sold in Havana, Cuba.

While being transported to Cuban plantations, the Africans broke their irons, killed the captain, and commandeered the schooner Amistad in an attempt to sail back to Africa. After two months at sea, the vessel docked on Long Island Sound, and was captured by the U.S. Navy, sparking a legal battle over whether the captives were property or free people.

The reenactment traced that legal dispute through the federal courts, culminating in the 1841 Supreme Court decision delivered by Justice Joseph Story, which found that the Mende on the Amistad were not slaves under Spanish law and could not be returned to Cuba.

The court overturned a portion of an earlier Circuit Court decision that ordered the transfer of the Mende to the president, to be returned to their homes in West Africa.

Though the ruling left them without funds to return home, the Mende captives partnered with abolitionists to raise money for their passage. In November 1841, the survivors finally set sail for Africa.

After the performance, legal experts from Fordham Law School contextualized the Supreme Court’s decision finding the Mende people to be free. Importantly, the decision did not reject slavery on principle but said that the 35 Africans in the case were not enslaved legally.

By contrast, an enslaved young Afro-Cuban cabin boy Antonio was treated in the decision as the personal property of the deceased captain.

Fordham Law professor Norrinda Brown called the decision a perfect example of “interest conversions.”

“The country’s desires in international law and internal politics converged with the desires of the Amistad,” Brown said. “We are not surprised that we go on to have slavery exist in this country for many decades after this decision. This was more about the United States’ interests than the human people whose lives were at stake.”