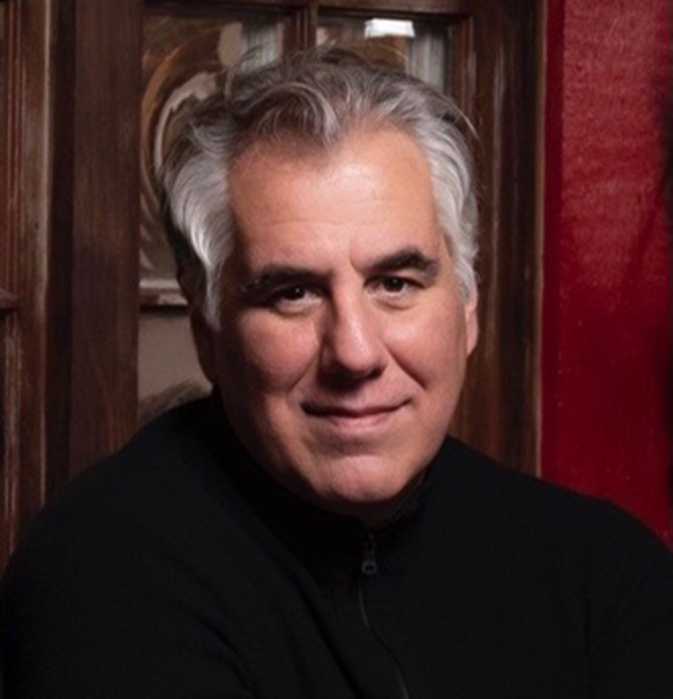

Staten Island District Attorney Michael McMahon has built his reputation as a prosecutor on an approach to the opioid epidemic that is surprisingly unorthodox for a politician in a conservative borough.

“One of the reasons I ran to be district attorney is because I realized that this was an office that could have an incredible impact on issues in the community beyond the traditional role of the prosecutor,” McMahon told amNY Law. “This office has incredible power when it seeks to advocate within government. And within the larger community.”

But shortly after creating a successful diversion program to connect opioid addicted individuals in the borough with supportive services rather than prosecute them, McMahon’s efforts collided with sweeping changes to criminal justice under the Legislature’s bail reform program.

In his view, the 2019 bail reform law derailed the effectiveness of his Heroin Overdose Prevention and Education (HOPE) program by delaying the defendant’s “initial engagement” with law enforcement and social workers.

“They always go too far,” said McMahon, a Democrat, of the Democrats in the state Legislature.

McMahon has overseen the office during an era of expansive criminal justice reform in New York state, which has pushed him into a more defensive right-leaning position in contrast. For district attorneys in New York City, the desire to reform has led to a progressive prosecutor movement that aims to use discretionary powers to reduce incarceration. Some of his fellow prosecutors, like Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, have come out against charging certain low-level offenses that fall under crimes of poverty, such as fare evasion and prostitution.

McMahon sees this as a political stance that the district attorney’s office has “no place for.”

“If someone commits a crime, we’re gonna prosecute it. I don’t dismiss cases wholesale or say that’s not a crime,” he told amNY Law, adding that “If you think something should not be a crime, you have to go to the state legislature and get them to change it. Why don’t they change it if they don’t think it should be a crime? But that’s up for the legislature, not me.”

Yet declining to prosecute cases defines the model for his pioneering HOPE program, a pre-arraignment diversion policy that redirects low-level drug offenders to community-based health and treatment services. If an individual follows steps assigned by a peer navigator, McMahon will not prosecute the case.

While it cuts against a strict law-and-order approach to prosecution, McMahon treats drug addiction differently than other categories of crime, an approach he believes to be in line with his constituents. He added he felt he had to narrow the scope of the program, excluding people with more severe criminal records, for instance, to make it palatable to Staten Islanders.

“Listen, I’ve got to sell these things to the larger community in Staten Island,” McMahon said. “So if I am dismissing cases, if you will, I’ve got to keep the support of the people of Staten Island for what I’m doing.”

This pitch has seemed to work. McMahon ran for reelection unopposed in 2023. As a former Democratic Staten Island member of the City Council and congressman in the conservative enclave, McMahon has had to learn how to camouflage himself from Republicans.

Staten Island is in many ways the political exception to the other four boroughs. It’s represented by the city’s sole Republican member of Congress — Rep. Nicole Malliotakis — and a place where local lawmakers semi-regularly threaten secession from the city.

But when McMahon took over as district attorney that exceptionalism also pertained to addiction. In the 2010s, Staten Island had begun surpassing the rest of the city in opioid related addiction and overdoses. During McMahon’s campaign for district attorney, he said that he started anecdotally hearing about the epidemic from community members, family members — “and believe it or not a lot of the funeral home directors” whom he spoke to on the campaign trail.

“Why Staten Island? Because in many ways, Staten Island’s demographics from population, from economics, to work history and what people do is much more similar to Middle America, places like West Virginia and Ohio than it is like the rest of the city of New York,” McMahon said.

Public sector employment is high on Staten Island, which has the highest number of union members per capita out of all five boroughs, according to research conducted in 2021 by the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies. Police, fire, sanitation and building trades are common jobs in the borough — jobs that involve physical activity and can lead to injury.

“The over-prescription of opioids was rampant here on Staten Island. We have one of the highest prescription rates in the state of New York,” McMahon said. “When you put those together, you had a high addiction rate, and as the pills started to be curtailed, everybody switched to heroin, and that’s where you saw overdoses.”

For 10 months after he was elected, McMahon sat around a table and talked to the defense bar, Legal Aid attorneys, health community officials, addiction service providers, the NYPD and city health department to craft the HOPE program. His office opened it in 2017, and by many metrics it has been a success. McMahon said that about 2,000 individuals have gone through the program since, and overdose deaths have slowed each year, according to state data. 2024 was the first year that Staten Island has seen a decrease in fatal overdoses since the pandemic. Overdose deaths had temporarily dipped in 2017 and 2019 after HOPE was first created.

But the program’s effectiveness relied on the moment after someone is arrested, McMahon said, when they’re sitting waiting in a police precinct to get arraigned, and a peer specialist meets them to offer them supportive services.

“You’re kind of at an inflection point, right? You’re sitting there, ‘what am I doing with my life? What’s going on?’ Somebody comes in and gives you an offer of hope,” he said.

The frequency and structure of those encounters changed two years after HOPE’s rollout, when the state Legislature passed bail reform, setting the tone for McMahon’s antagonistic relationship with the state legislature.

“With the advent of justice reform, now [in] a lot of low-level cases, you get a desk appearance ticket, and you don’t have to come back for 20 to 30 days,” he said. “And so we don’t have the initial engagement like we used to.”

His position on bail reform — that it works against law enforcement — is consistent with other proposals by the City Council and state legislature. In his 2023 annual report, he called City Council members and legislators “idealistic” and “naïve” for proposing Albany’s “Clean Slate” legislation which automatically seals criminal records and the City Council’s “How Many Stops” bill to mandate police reporting of nearly all routine encounters.

Most recently McMahon has taken a front-and-center role in Governor Kathy Hochul’s campaign to roll back Discovery Reform in the state budget. In mid-April, he appeared with Hochul and other city DAs to argue that many judges are dismissing cases on technicalities rather than taking into account good faith efforts to meet filing deadlines.

“[With] the volume of work that these hare-brained discovery laws have foisted on prosecutors, cases are being dropped or dismissed because they can’t handle the workload. Is that what we want to happen?” he asked amNY Law.

Asked if he believes in the stated intention of the law to provide transparency for defendants and make cases more expedient, he conceded that he did, but continued to rail against scope of documents that it covers as so “unrelated to the case” that it’s “lost all meaning and purpose.”

When the conversation moved to issues such as immigration that are more national in scope, McMahon took a tone that skewed more liberal. Like Brooklyn DA Eric Gonzalez, McMahon created an immigrant affairs unit with an attorney who can advise his staff on the consequences that cases could have on individuals’ immigration issues.

Asked if he disagreed with ICE agents from arresting people inside New York State courthouses or when they are on their way to or from court without a judicial warrant or court order, McMahon at first hedged that he hadn’t seen much immigration enforcement activity in Staten Island.

But pressed on the issues, he said, “I believe in our constitution. I believe in our bill of rights, and if somebody’s rights are being impinged upon by the government or anybody else, I’m going to stand up for them. We look at it on a case by case basis.”

District attorneys should not be making policy or legislating, he added, before snapping back into his belief about the need for district attorneys to rigidly adhere to the laws as written.

“If someone commits a crime, we’re gonna prosecute it. I don’t dismiss cases wholesale or say that’s not a crime,” he said.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story has been corrected to reflect that overdosed deaths in Staten Island decreased in 2017 and 2019.