Richard Brodsky, the founder of software company Sandata and founder and chairman of Mobile Health, saw a problem when it came to hiring more home care aides. It took time to clear them medically and get approvals from their doctors.

So in true entrepreneurial spirit, he rolled out mobile and then fixed clinics to test prospective aides, getting results within two days while developing CareConnect, a company to train aides, so those who qualify could get to work.

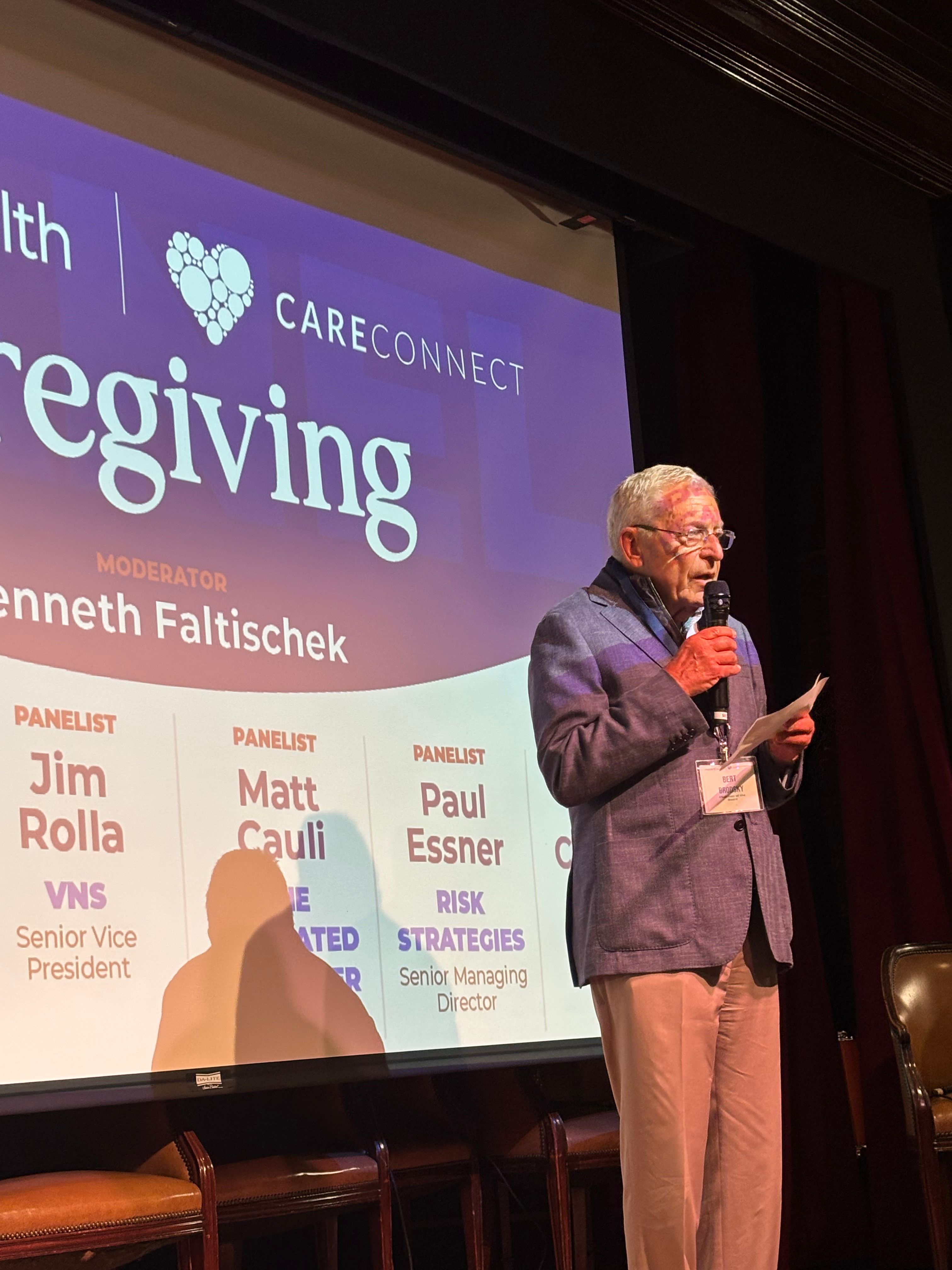

“We kept the mobile vans. We still use them. That was the genesis of Mobile Health,” Brodsky said recently at a kind of caregiving summit that Manhattan-based Mobile Health organized at the Players Club in Manhattan. “Mobile has always been important to me.”

Amid a veritable explosion of demand for home aides in New York City, and on nearby Long Island, the home care aide industry is at a crossroads, facing growing demand and new challenges. Demographics drive part of the change, amid a booming Baby Boomer population.

“The population is increasing in age,” Judy Zangwill, executive director for Sunnyside Community Services in Queens, said at the September 9 event that attracted hundreds. “And Queens has a significant aging population.”

Systematic shortage

While you might think of medicine when it comes to healthcare, home care aides actually provide the missing piece to the puzzle, helping with activities of daily living such as bathing, cooking, cleaning, laundry and taking medications, but not skilled medical care.

“They would be in a nursing home or assisted living,” Zangwill said of patients without this care. “People want to stay in their homes and their communities, if we can provide sufficient support for that to happen.”

About 95% of home care providers report severe staffing shortages while 53 million Americans provide unpaid caregiving. Even as need surges, this industry is facing issues. The federal government revoked immigration status of thousands who had been here legally.

“One of our home health aides had temporary protected status that wasn’t renewed. She worked for us for 24 years and she lost her job,” Zangwill said. “Nationally, there is a shortage. We don’t have a shortage yet, but we’re concerned that we will.”

Tracy Walsh, patient care director for Bryan Skilled Home Care in Queens, said they had about 15 aides whose status was revoked.

“We had to find other caregivers to replace them. They were really good,” Walsh said. “It’s not an easy job. You go into everybody’s house. You have to meld in with the family.”

New York numbers

New York City Department for the Aging Commissioner Lorraine Cortes-Vazquez said there are 1.3 million caregivers in New York City. “We have to make sure they get support,” she said. “They’re an invisible workforce.”

Cortes-Vazquez and others believe it’s easier to get support to care for children than for ill or infirm elderly, even if that can be equally essential. “If it weren’t for agism, we would put a lot more resources in this area,” she said.

Chris Durrance, director and senior producer of “Caregiving,” a documentary about caregiving, said “policies in support of care for a parent or loved one are hard for employees” and “not as tax-favored as childcare.”

“The deficit in caregivers we have is going to hit all of us really hard,” Durrance said. “Taking this out of the shadows can force change.”

Jim Rolla, senior vice president of VNS, noted that “caregivers continue to be lower wage workers.”

Meanwhile, Al Cardillo, president of HCA-NYS, said it’s important to offer a competitive salary. “Sometimes home health agencies are competing with their own health systems, their own hospital,” he said.

Rolla said companies need to compensate and provide benefits as well as recognition. “Make that a part of your everyday operation the same way that you deliver care,” he said. “There’s a recognition today that that’s much more important than ever.”

Walsh, who said her company has about 600 active caregivers, including around 30 percent who are male, said keeping people out of institutions can be healthy and economical. “It saves money over hospitals,” she said.

The recruiting RX

You can only provide as much care as you can based on the number of providers. Tatiana Terekhina, director of strategy for All Heart homecare agency based in Brooklyn with clients across New York City, said it’s a rapidly growing industry.

“We make sure we are visible, present, people know us. We have a terrific reputation,” she said of recruiting. “The mission of our company is to offer as much help and help as many people as possible.”

She said the majority of their patients come from referrals and it’s important to provide a wide range of languages.

“We have caregivers from different backgrounds,” Terekhina said. “Spanish, Russian, English, Creole, Polish, Ukrainian, Greek, Italian. Any request a patient has. It’s our mission to make sure they’re comfortable.”

Brodsky said a wide range of people work in this industry from “all ages, sexes, backgrounds,” often paid by Medicaid.

Deodat Somaiah, fiscal director home care for First Chinese Presbyterian CAHAC, specializes in care in Chinatown.

“The majority of the population is Chinese. We care for other individuals too,” Somaiah said. “We try to match the people requesting services with individuals, making sure they have skill sets. Language is one of them.”

Terekhina said they have about 2,000 caregivers and currently serve about 1,500 patients, providing companionship and assistance with daily life activities.

“They help them with personal care, to take a shower, cook food, do shopping. Imagine someone has mobility issues,” Terekhina said. “They have a hard time getting out of the house. They cook and clean for them, accompany them to doctor appointments.”

They remind people to take medications, but don’t typically hand them the medications. “We don’t give them injections,” Zangwill said. “Some have to be transferred from a bed to a wheelchair. Our aides are trained to do that.”

Screening support

Brodsky said Mobile Health helps bring new people into the industry by doing prompt, thorough medical screenings for home care workers, checking height, weight, blood pressure, drug screenings, and testing for sexually transmitted disease.

“We make sure you’re eligible based on state regulations to work in somebody’s home,” he said. “They couldn’t go to work without screening.”

Mobile Health has clinics in every borough and beyond, screening 500,000 home care workers annually, along with employees for some other industries.

“They can have high blood pressure and have to be treated,” said Brodsky, who noted they outsource background checks. “Most clear, but many don’t.”

Brodsky’s other company, CareConnect, does education and training which needs to be done for workers to qualify to work in homes.

“Would you rather be at your home and get everything in your house versus being in some facility,” Terekhina said. “At home, you have a caregiver watching.”

Paul Essner, senior managing director at Risk Strategies, said nonprofits and companies have limited resources. “It’s not as though they have unlimited sources of cash to turn around and create programs,” Essner said.

Friends and family

In addition to professionals, many loved ones can be compensated for providing care through CDPAP, or the “Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Program.”

Under this program, consumers can hire their family members or friends as their personal assistants paid to provide care typically through Medicaid.

“When we talk about caregivers, we’re not only talking about employees who work for agencies,” said Mobile Health CEO Kenneth Faltischek. “We’re also talking about family members who care for family members.”

The federal government found fraud among caregivers helping family members. Leading to changes in this program.

“It’s fraud if a caregiver clocks in and says they’re with patient, but not with that patient,” said Denise Tavrez, director of business development for Bryan Skilled Home Care.

After finding fraud, the federal government revised protocols. “The program changed dramatically. The verdict is still out,” Zangwill said regarding the new version. “It’s in the process of changing.”

Helping the helpers

Organizations work to support caregivers, as well as those needing care. “We have caregiver programs, for people over sixty,” Zangwill added. “It’s so stressful. We try to provide as much support as we can to caregivers. We have support groups, educational programs.”

Bradley Cooper, one of the executive producers of the documentary “Caregiving,” helped care for his father.

“He was at a point where he needed a lot of care. I was lucky enough that I was able to be there for him,” Cooper said in the movie. “And I benefited from the help that we also got. These are heroic people, caregivers.”

Paul Irving, a senior advisor at the Milken Institute, in the documentary, may have said it best when he noted we need to judge society based on how we care for each other.

“How do we measure the success of America? Is it just GDP?” he asked. “One of the ways is to measure success in providing care. In the next version of America, could care be a driver of our success?”