The city reduced bike and e-bike speed limits in Central Park from 20 to 15 mph — but many Central Park visitors say it is almost impossible to enforce, and it keeps no one safe.

During a joint meeting of Manhattan Community Board 7’s Parks, Environment, and Transportation Committees on Jan. 12, the panelists sought to find a safety solution for all concerned.

Representatives from the NYPD, the Central Park Conservancy, and the city’s Department of Transportation joined the session, along with local residents who often stated that Central Park — New York City’s most renowned public greenspace — is facing an influx of cyclists and e-bikes that often speed through the park, endangering lives.

Sam Schwartz Engineering in 2024 completed a 77-page report for the Central Park Conservancy, which found that 42 million people use the park annually, with pedestrians comprising more than half, including many who sometimes feel unsafe crossing roads.

Esteban Doyle, of the Department of Transportation, said the study was done to “improve safety and comfort in the park, better allocate space for users, create better separation and improve crossings.”

Since then, the DOT has embarked on efforts to make Central Park’s roadways safer for pedestrians and bicyclists alike. The first phase of improvements, completed last year in the northern section of the park, impacted roadways south of 96th Street on the west side and 90th Street on the East Side — and included new markings, images, colored parts of the road, and yellow caution lights replacing the traditional red, yellow, and green stoplights.

The safety improvements, however, have done little to quell anxiety among parkgoers.

“A lot of pedestrians are scared,” Chair of the Parks and Environment Committee Barbara Adler said regarding a resolution written but not voted on at the meeting. “We wanted that acknowledged by DOT and others. What’s happening now is great for some bikers, but it’s not great for pedestrians.”

E-bikes and bikes

Some believe bikes, electric bikes, or e-bikes, and pedestrians are sharing the road well in Central Park with new markings only improving things.

“When I’ve been in Central Park, it’s never been a problem with people crossing,” said Ira Gershenhorn, a cyclist who lives near 104th St. and Riverside. “People get across.”

Some residents who use e-bikes, including CitiBikes to cross the park, say access to Central Park is crucial to their own safety.

“It’s important to me to have various modes of transit so I can safely get to where I need to be,” Sarah Sachs said. “Otherwise, I’d be forced outside the park, which feels dangerous and congested.”

Yet other pedestrians can easily find themselves in a perilous situation in the crossfire between bikes and e-bikes.

“Central Park is vital to this city. It brings so much to us. I use it quite a bit. I almost never feel comfortable crossing,” said Lesley Friedland, a West 72nd St. resident.“We need to have everybody feel comfortable and enjoy it.”

A design that favors two wheels over two feet?

The NYC E-Vehicle Safety Alliance, including about 1,400 people, believes the design “prioritizes e-vehicles over pedestrians/runners” and created an “e-bike super highway for faster food delivery and commuters to cut through Central Park.”

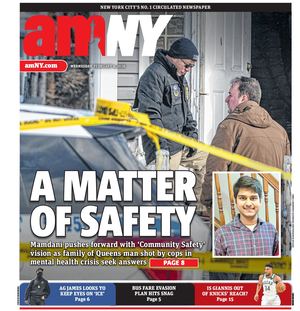

Schwartz Engineer’s report indicated that from 2018-2222, there were 522 collisions, 472 injuries and one fatality, while others said the numbers are much higher.

Victims of collisions inside Central Park said their cases underscore the need for keeping e-bikes out.

Upper West Sider Renee Baruch, the victim of a Central Park e-bike accident in 2023 for which she was hospitalized for a week and had multiple surgeries, believes e-bikes are particularly perilous in the park.

“These things are horribly dangerous,” she said, noting she and others documented 15 accidents, including three with EMS vehicles, when “police reported one accident.”

Columbus Circle resident Roberta Simon was running in Central Park when she was hit from behind by a 15-year-old on an e-bike. She woke up four days later after brain surgery.

“E-bikes should not be in the park. They are motor vehicles,” she said. “A common thread is enforcement. There is no enforcement. There are a lot of accidents that happen that are not reported.”

The NYC E-Vehicle Safety Alliance wants to ban e-bikes from Central Park, where they believe they result in hundreds of injuries.

“I do not understand why e-bikes are allowed in our parks at all. Parks are not for the purpose of transportation. They are there for recreation,” said Summer Gentry, member of NYC-EVSA. “E-bikes are especially dangerous, incredibly heavy vehicles. Getting hit by an e-bike is so severe.”

While legislation is being considered to license and register e-bikes, some residents would like to see them banned from Central Park, while others view them as an important means of navigating large areas of territory.

“I use an e-bike to get my son across town. We have a lot of stuff we have to carry,” said Trevor Shade, of West 82nd Street. “I believe it’s a necessity to have that benefit.”

Some others said that bikes as well as e-bikes routinely speed, putting pedestrians at risk.

“I literally sprint across the crosswalk to avoid cyclists,” Upper Westsider Jake Smyth added. “They don’t stop. They didn’t stop when it was a red light. They don’t stop when it’s a yellow light.”

Enforcing the law

Many residents questioned whether existing speed limits or reckless riding rules are being enforced for e-bikes or bicycles, which they say often exceed the speed limit.

Deputy Inspector Timothy Magliente, commanding officer of the Central Park Precinct, stated that over 100 summonses were issued for e-bikes last quarter.

“Cops are out there enforcing the law. Speed enforcement is not easy with bicycles,” he said. “The frame of a bicycle is narrow, which makes it impossible to shoot Lidar. Speed enforcement is tough.”

Magliente said it’s easier to give summonses for reckless operation of a vehicle when bikes or e-bikes are operated dangerously. “We issue a lot of summonses for violations of bikes not on the right paths,” he added. “We issue some for bikes going the wrong way on the drive.”

Some tickets are returnable to traffic violations, some to administrative court, and some to community court in what Magliente called a “mixed bag of summonses.”

Bill Castro, former chief of parks in the borough of Manhattan, said enforcement is tough, beyond sporadic crackdowns.

“The plan to divide the park into lanes is a good idea. Enforcement will be very difficult,” Castro said. “They’re effective briefly, but then enforcement goes away. It will be difficult to enforce the speed limits and lane separations.”

Some worry that enforcement could penalize cyclists when there are no pedestrians nearby.

“I am concerned that the speed limit may be too low for those areas of the park that are downhill after really difficult uphills,” said Susan Zinder, suggesting that downhill have higher limits.

“They are still subject to the rules of the park,” Magliente said of cyclists racing by even in the morning with fewer people in the park. “They have to do it in a manner that’s safe to the public. They’re not exempt from the law.”

Magliente said last quarter police handed out about 4,000 fliers in Central Park about pedestrian safety. While some suggested cameras might help, he said cameras generally prove problematic.

“They just slow down for the camera and continue to speed,” he said. “We see that in many areas where we put speed cameras.”

Andrew Rosenthal, an Upper West Side resident, said there are 60 miles of park pedestrian paths and seven miles where bicycles are allowed.

“We need to share those seven miles,” he said, noting that Central Park the “only place safe for a cyclist to work out.”

Magliente said police have set up machines recording and displaying actual speed, while reminding of speed limit.

“If we recognize that there needs to be raised crosswalks at some locations to slow people down, that’s something we could continue to talk about,” David Saltonstall, the Central Park Conservancy’s Vice President of Government Relations, Policy and Community Affairs, said. “Hopefully, everything will get worked out at some point in the near future. This is an ongoing process.”