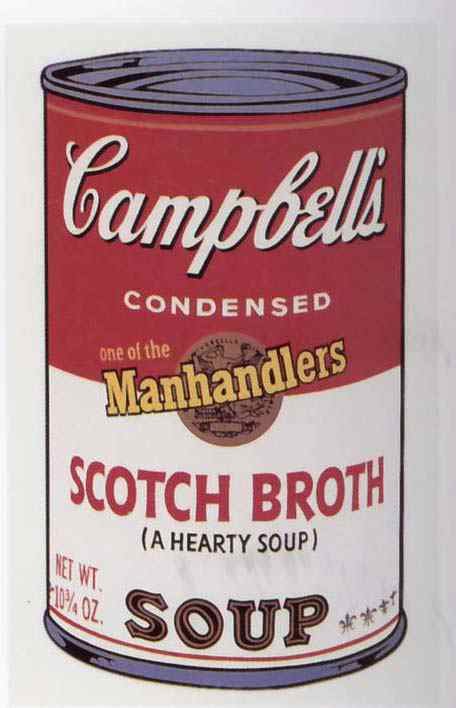

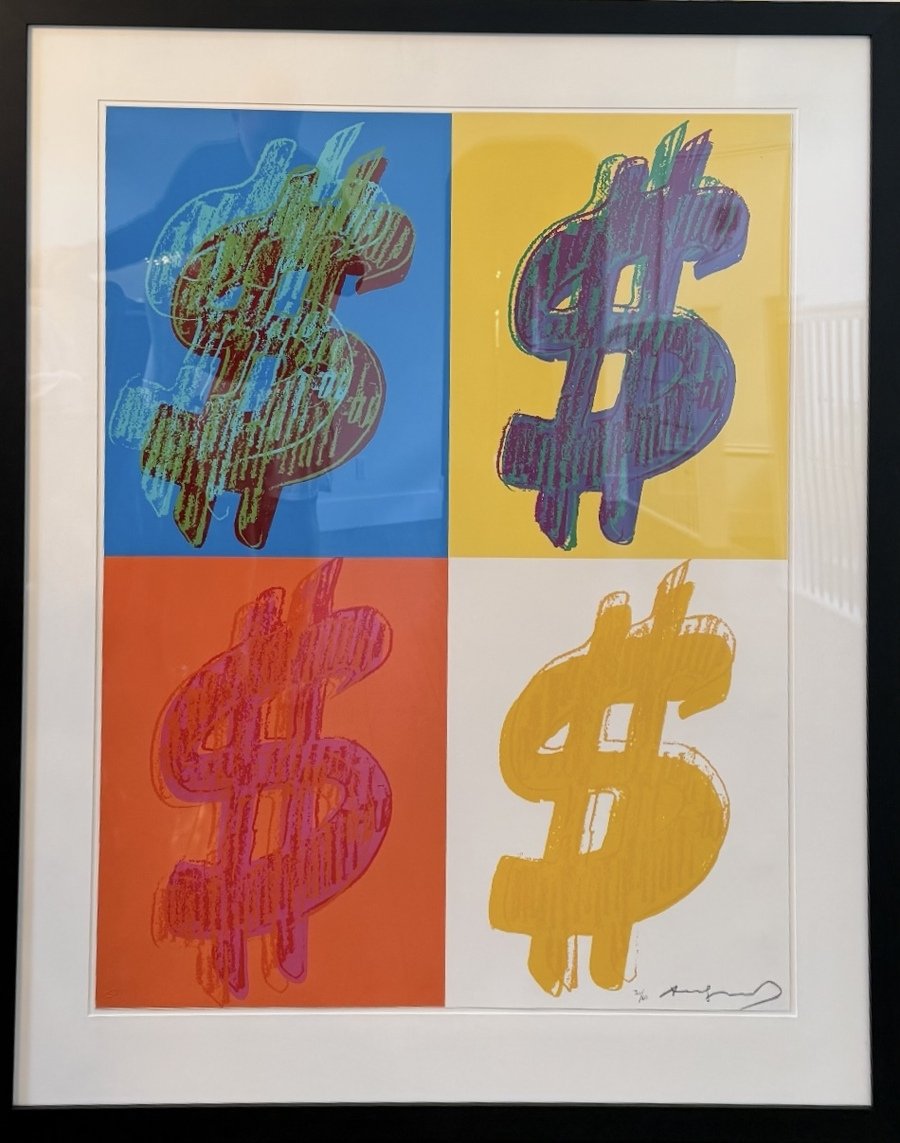

There is a peculiar kind of poetry in processed food—specifically, the kind that arrives wrapped in corporate sanctimony and sealed in the aluminum stillness of a Campbell’s soup can. In Andy Warhol’s hands, this was no mere grocery item. It became a relic of American ritual, a postmodern totem of appetite, identity, and mass production.

Few artists understood the artifice of branding better than Warhol. He did not simply paint consumer goods; he canonized them. His soup cans—spanning flavors from the mundane to the absurd—mirror the emotional topography of a country addicted to convenience, repetition, and self-image. Yet two flavors in particular demand renewed consideration: Tomato Beef Noodle O’s and the rare, imagined Maneater Soup. Each presents a case study in cultural craving—one nostalgic, the other carnivorous.

Tomato Beef Noodle O’s is not merely a meal-in-a-can; it is a meditation on American longing. Warhol’s rendering of it preserves more than flavor. It preserves an era—a nation perched on the edge of Cold War anxiety, distracted by circular pasta and television dinners. The “O’s” in their strange serenity echo the looping monotony of capitalist desire. One could call it a portrait of consumption itself—endless, canned, and comfortingly sterile.

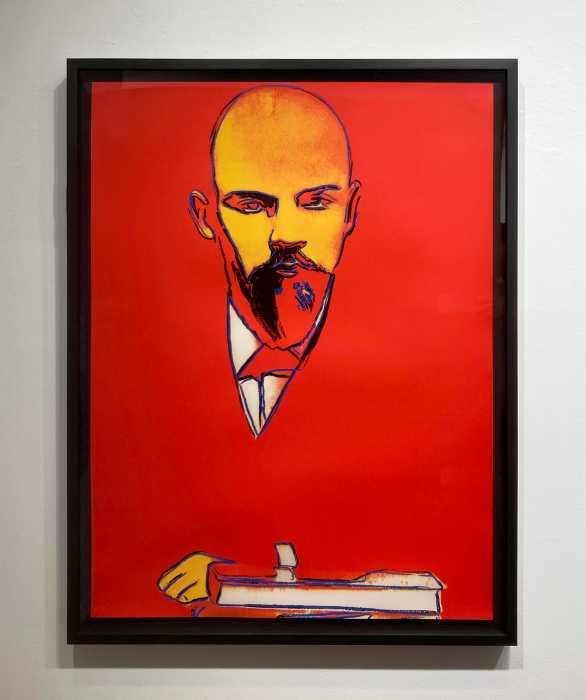

By contrast, Maneater Soup strikes a more subversive note. Conceived during Warhol’s Maneater portfolio in the early 1980s, it weaponizes the iconography of consumer culture to deliver a darker message. This fictional flavor does not soothe; it seduces and devours. The label reads like a warning. In it, the female form is not soft or passive. She is hungry. She is branded. She is brilliant. Warhol, ever the provocateur, rendered femininity not as muse, but as market force—a commentary as relevant now as it was then.

These cans do not merely hang on gallery walls. They reverberate. They are a coded language for those fluent in irony and desirous of legacy. To own one is to participate in a lineage of cultural critique wrapped in the aesthetics of Americana. It is also, quite plainly, a strategic decision.

In the current art market cycle, Warhol’s soup cans—particularly rarer editions and portfolio variants—have entered a moment of high velocity. With financial institutions and legacy collectors once again circling around blue-chip Pop art as both a hedge and a statement, the opportunity for acquisition is both urgent and finite. The surge is not speculative. It is generational. It reflects a larger appetite for objects that embody both critique and value.

DTR Modern Galleries, with its direct access to Warhol portfolios and an established history of connecting discerning collectors with museum-quality works, stands uniquely poised to navigate this moment. Through carefully curated private offerings and a deep knowledge of provenance, the gallery offers clients not only access, but alignment—with one of the most enduring figures in contemporary art and one of the most compelling cycles in the market to date.

To collect Warhol now—particularly pieces such as Tomato Beef Noodle O’s or a portfolio print from the elusive Maneater series—is to claim a fragment of cultural DNA. It is to hold, quite literally, a mirror to the American psyche. These works are not simply icons; they are inflection points, revealing who we were, who we became, and what we are willing to digest in the name of identity.

Warhol famously said, “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art.” His soup cans are proof. They are not merely good business. They are exceptional.

For more information on these types of portfolios, follow @dtrmodern and dtrmodern.com.