By Janel Bladow

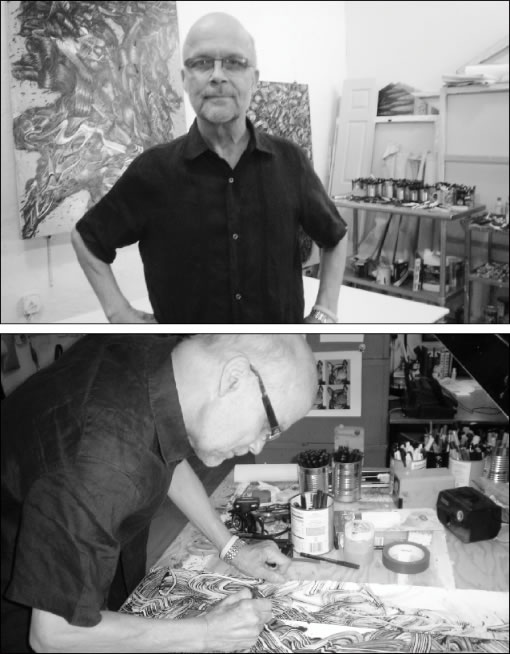

“I love a black line,” says artist Paul Jansen strolling through his South Street Seaport painting studio, surrounded by tables topped with brushes, acrylic tubes, colored markers, and canvases covered with seven to eight coats of silky smooth white enamel. Huge and small paintings hang from the white walls, nearly all swathed with squiggly black lines.

“I’m adding dimension which wasn’t allowed in the original abstract expressionism,” he says, pointing out the depth that can be seen in his paintings. “I’ve always been attracted to the style. Very organic. Slap paint on then brush or squeegee it off.

“My paintings have been very passive, not very dramatic, relatively lyrical,” he says, adding almost wistfully, “then I got sick.”

Jansen, 64, was diagnosed with lung cancer a year and a half ago, which spread into his adrenal glands. After several operations, chemo treatments and bouts with pneumonia, he’s battling back and recently gained nearly 15 pounds. “I’m on chemo for life….until a miracle comes through the door.”

His body has responded well — his tumors are shrinking and his test numbers are strong. His prognosis is good for now. But until recently it’s been a struggle to paint.

Then he learned a few weeks ago that he will be awarded a Pollock-Krasner grant this week for emerging and established artists who face obstacles to creating their art.

“Cancer is one,” he says with a wry laugh. “Cancer has resurrected my art career.”

Lee Krasner, widow of artist Jackson Pollock and a recognized abstract expressionist painter in her own right, established the Pollock-Krasner Foundation in 1985 to give financial help to working artists. Since then, more than $46 million has been given to artists in nearly 70 countries, according to the foundation Web site. The grant is intended to support the artist’s artistic or personal expenses for 12 months and this year averaged about $15,000.

“After cancer, I’ve become more animated in my application of paint,” he says of how he plies on the black then, with handmade rubber squeegee-like brushes, swirls, swoops and glides the paint into what looks like wavy layers of ribbons. “I live to keep painting.”

Color has seeped into his canvases, first subtly with soft pastels and now with bold, dramatic orange reds. He adds the color after the black painted ribbons have dried with markers or by brush. Finally he applies hundreds of thin, mini crosshatches in some paintings for added depth.

“I’d say I’m re-creating abstract expressionism in a cartoonist way,” he adds with a flourish. “More aggressive, dramatically so. I see anger, frustration, more joy coming through than I did before.”

Born in Boston, Jansen grew up in Stamford, Conn., the second son of a merchant marine sea captain and a housewife. When his father returned from sea and later retired, he spent his time painting and woodcarving.

“My father was self-taught, quite the craftsman with his hands. He painted until he was in his eighties and was a member of the Stamford Art Association. There wasn’t a member of our church who didn’t have one of his paintings. He did these three-by-two cubist-style abstracts.

“But my mom claims my artistic talent came from her,” he says with a laugh. “She started painting at 16 and was pretty accomplished.”

Jansen started his artistic way by copying Mad Magazine then evolved into his Escher-esque drawings. He dreamed of being a pinstriper of hot cars. “I was good at monogramming. Lousy with a straight line.”

Like most teenagers in Stamford in the ‘60s — and today — Jansen knew more about what was happening in New York City than in his hometown. He made frequent treks to the Big Apple to hang out and visit museums.

After a stint in the Navy, Jansen returned to the city where he graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a fine arts degree. He received many postgraduate awards and established himself as a freelance illustrator.

But his big break came when he was named resident artist at Jimi Hendrix’ Electric Lady Recording Studios where his brother John worked as recording engineer. Jansen was designing the offices while Hendrix was on his last worldwide tour.

“I never got to meet him,” he says of the guitar legend, who tragically died in September 1970. “He was in England and never made it back.”

But Jansen does have a lasting connection to Hendrix. He did the cover art on two posthumous albums, “War Heroes,” (1972) a stippling-effect black and white portrait, and “Loose Ends,” (1974), a muted photorealistic triplex.

A longtime Downtown resident, Jansen and Delores, his wife of nearly 20 years, and stepdaughter Ashley Pickett, moved from Soho to Ann St. where they were living on 9/11. Soon after they made the move east a few blocks to Dover St.

“It’s much more of a neighborhood,” he says, noting that he’s made many connections as a co-coordinator of the Fish Bridge Dog Run at Pearl and Dover Sts. (Full disclosure: this reporter is one of the other co-coordinators). The family’s French bulldog Petunia is a tiny terror with a rubber ball.

Through a dog run connection, last year, Jansen painted a skateboard to raise money for breast cancer research. He was in good company. Robin Williams and Julian Schnabel were two of the other nearly 50 artists involved.

And another dog run connection led to a unique Downtown exhibition space, the Salon 2B hair salon at 80 Nassau St.

“What I’m painting now, I saw in a dream after I read a book on Franz Kline,” he says of the abstract expressionist best known for his black and white paintings. “Less curves. Take a risk with more color. More dimension.”

And, like Kline, more action.