BY SUZAN MAZUR | “It was an ant with a crumb twice its size in its jaws slowly making its way over the twigs. It occurred to me that if I was that little ant, the shrubbery would look like a great forest, and so with my face close to the ground, I tried to view the scene as my minute energetic acquaintance was observing it. In a moment the twigs became great fallen trunks, the dried spruce shrubs turned to gigantic trees with twisted branches and I was looking into a forest out of the depths of which a band of Nibelungs laden with gold and silver treasure, and even Wotan himself, might have come.”

— Edward C. Caswell, “Artist Draws the Narrowest City Dwelling,” The Villager (1933)

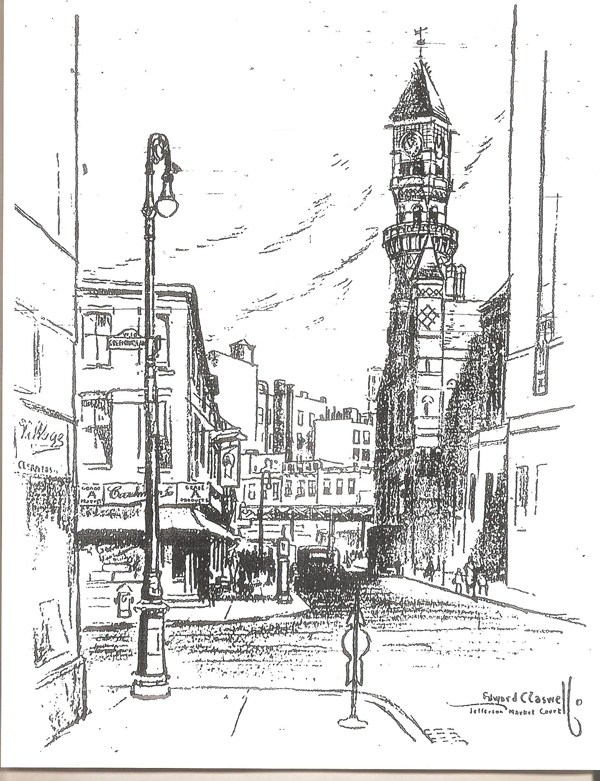

Before the West Village became one of America’s financially richest zip codes, a neighborhood of noisy outdoor eateries, Madison Ave. shops and streets cordoned off by TV crews, it was a quiet place to live, a culturally rich community, one that Edward C. Caswell (1879-1963) delightfully illustrated for decades.

Throughout the 1930s and ’40s, Caswell’s drawings appeared regularly on The Villager’s front page.

It was in the bound volumes of old issues at The Villager’s Canal St. office where, last year, I had my first glimpse of the range of Caswell’s fascinations.

Caswell wrote an occasional column for the paper as well. And he was a book illustrator, traveling to Europe in the 1920s, capturing Florence, Amsterdam and Budapest with pencil and pen and ink.

I was intrigued when some of these illustrations popped up in the local flea market. My favorite are the artist’s portraits of the West Village streets, of the interiors and exteriors of the homes of its residents, like poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, who lived in New York’s narrowest house, a Dutch house — once “a maltster’s, a cobbler’s and a candy factory.”

There is scant information about Caswell’s life. Why? I wondered.

Looking through the microfilm at N.Y.U.’s Bobst Library for his many covers of The Villager, it was clear to me that Caswell’s drawings were personal. He put his “face close to the ground,” knew the people, the art clubs and studios, the lanes and gardens he drew.

In 2006, Peter Duveen organized a show of the artist’s life and work at the Museum of Brooklyn Art and Culture in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Duveen noted that Caswell’s career “embraced newspaper work, advertising art and book illustration.” He told me Caswell started out at a studio in the Ovington Building on Fulton St. before moving to the Chelsea Hotel in the 1930s.

Duveen also said Caswell helped establish the Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibition.

The Villager, in fact, features Caswell’s drawing of the outdoor art exhibition on its May 4, 1933, front page with an accompanying story saying that it was the show’s third year, and that it was the first such event of its type in America. It was the Depression and the article notes the umbrella organizing group was the Artists’ Aid Committee. Five hundred artists displayed their work to 20,000 visitors.

Duveen asked if I’d be on the lookout in the Bobst microfilm for Caswell images of Bank St. where Duveen grew up — near the townhouse of “Auntie Mame,” i.e., Mrs. Tanner, playwright Patrick Dennis’s real aunt who lived at 72 Bank and inspired the character. Unfortunately, I could find no Auntie Mame in the Caswell trove.

Caswell wrote of the struggle of Edna St. Vincent Millay, whose house was on Bedford and Commerce Sts. near the Cherry Lane Theatre, to have the city rename Commerce St. “Cherry Lane.” The city refused.

Caswell also mentions in his column that actor John Barrymore once lived in the little Dutch house, and that Millay wrote her opera with Deems Taylor, “The King’s Henchman,” in the top-floor studio. When Caswell visited in the 1930s, the 8-foot-wide house was home to Mrs. Robert W. Lewis. He wrote that it was decorated with “rich and mellow” antique mahogany furniture and near the fireplace was a Victorian chair that “[G]randfather Lewis took around the Horn during the gold rush of 1850.”

New York’s narrowest house bears a red plaque with the dates Millay lived there (1923-24) and her famous quote, “My candle burns at both ends.” Across the street is 81 Bedford St. where late C.I.A. Director Richard Helms conducted his MKULTRA mind control experiments (no red plaque there).