BY MICHAEL OSSORGUINE | At long last, two boards are coming together to solve the financial woes of an East Village building and settle a dispute dating to 1996.

For two decades, the Housing Development Fund Corporation that manages 37 Avenue B has lacked sufficient income to pay property taxes and repair the building, which, according to tenants, is “literally falling apart.”

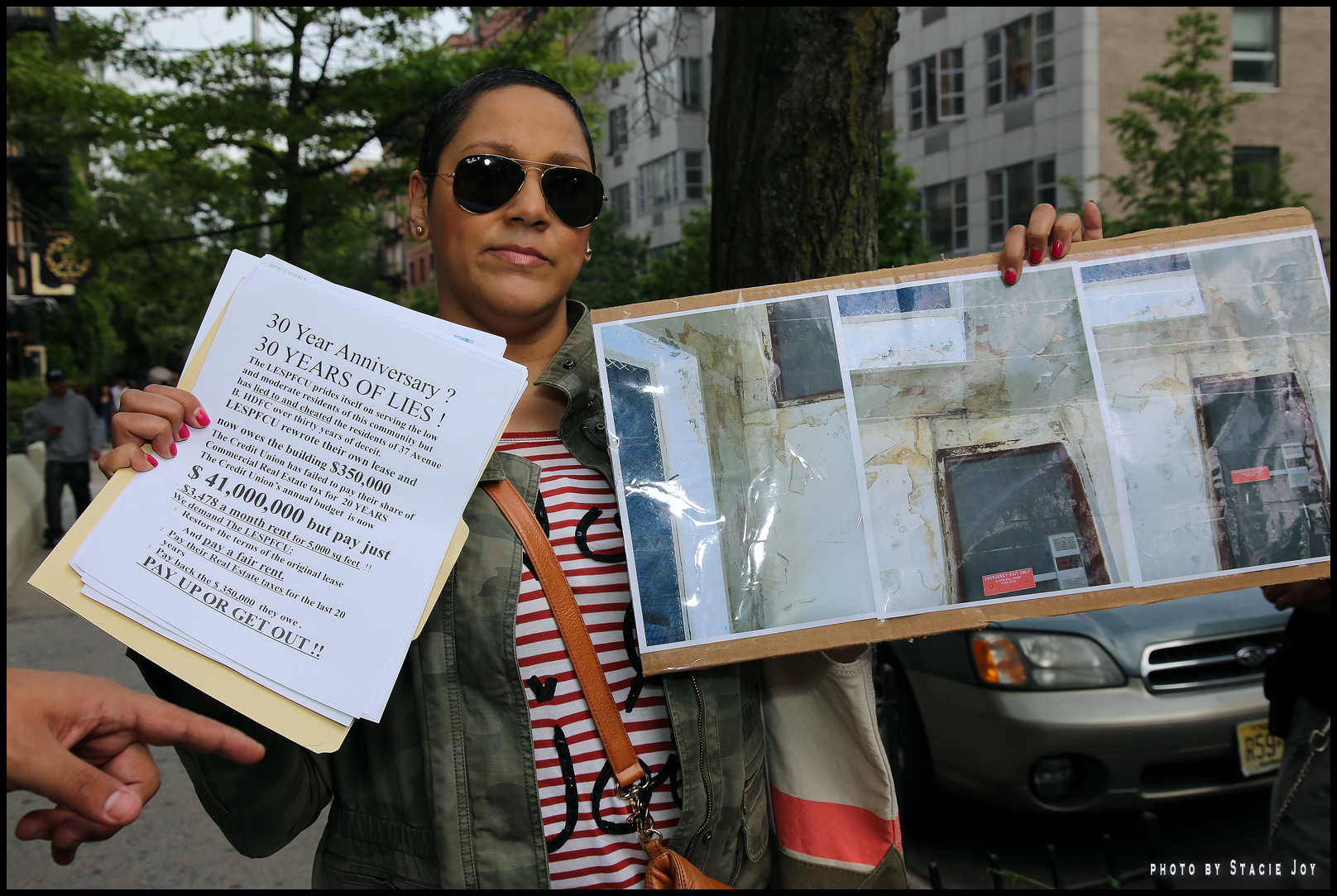

On Sat., May 14, the Lower East Side People’s Federal Credit Union, the building’s ground-floor tenant, held a celebration of its 30th anniversary. As they were doing so, building residents held banners and protested on the sidewalk outside, charging that credit union has not paid its “fair share” of rent.

Lisa Kaplan, an L.E.S.P.F.C.U. board member and former Community Board 3 chairperson, subsequently reached out to the H.D.F.C., whose members responded that they would be open to negotiations, which were set to start this month.

The H.D.F.C. is also headed by a board, and is a low-income housing co-operative. Earlier this year, however, all credit union representatives were purged from the H.D.F.C. board in an act of defiance by the co-op. The co-op’s corporation has six residential tenants — five tenants are rent-stabilized and one is rent-controlled. L.E.S.P.F.C.U. is considered a commercial tenant under the current lease, and has operated in the building since 1986.

The H.D.F.C.’s anger toward the credit union stems from amendments to the original lease that were drawn up by L.E.S.F.P.C.U. members and agreed upon in 1996. These amendments restricted raises of the credit union’s rent to 4 percent annually, and removed provisions making the credit union liable for increased property taxes on the building or payments on its mortgage.

Councilmember Rosie Mendez, who was on the credit union board for a period of time after the lease was signed, said that the agreement helped keep the credit union afloat since it was “operating in the red.” However, she now hopes that the building can come to a resolution.

“What I would love to see is the building to be financially viable,” she said.

However, others are criticizing the credit union for creating a selfish lease agreement that is ruining the building’s finances.

Frank Macken, a former credit union board member, slammed the credit union in a scathing talking point published in The Villager this past April.

“The People’s Mutual Housing Association management bookkeeper calculates the difference between the terms of the original lease and the amendment of 1996 at nearly $400,000 that the credit union has saved itself over 20 years, while gutting the building’s finances and running it into the ground,” Macken wrote.

The Lower East Side People’s Mutual Housing Association is a nonprofit, low-income property management and development organization that oversees the H.D.F.C.’s activities, and administers a number of other buildings in the neighborhood. Some of its members live in 37 Avenue B. For a period of time, the M.H.A. sublet 1,000 square feet of the credit union’s space. It now has offices across the street.

The building is accumulating debt due to its issues with structural damages and taxes, with an annual deficit of around $18,000.

L.E.S.P.M.H.A Chairperson Herman Hewitt said the building owes the M.H.A. nearly $60,000.

“I agree with the tenants, in that the credit union is not paying enough rent,” Hewitt stated. “The lease should be shorter and it should be updated every five years or so.”

However, Hewitt warned that if the credit union decides to leave the building, the credit union simply “will not survive.”

“A lot of things he said in that editorial were actually incorrect,” Deyanira Del Rio, chairperson of the L.E.S.P.F.C.U. board said, at the start of her rebuttal of Macken’s talking point.

According to Del Rio, who is an unpaid volunteer, the credit union is a benevolent financial co-operative. She said its annual budget is about $3.4 million, a far cry from the $41 million that Macken alleged. She pointed out that Macken confused their budget with its assets, currently valued at $45 million, which are mostly loans and investments made in the community.

Macken also wrote that the bank’s net income in 2013 was $1.41 million, but Del Rio estimates it at about a quarter of that, after factoring in grants that the organization received. The annual report for L.E.S.P.F.C.U. in 2013 states the institution closed the fiscal year with a net income of $525,390, attributing its growth to grants from the U.S. Treasury’s Community Development Financial Institutions Fund.

“We’re not swimming in cash, and I don’t think the tenants believe that,” Del Rio said. “We’re always operating at a small deficit.”

However, Macken retorted, “Crying poverty while exploiting rent-stabilized tenants is hypocritical.”

The credit union’s total employee compensation in 2015 was nearly $1.6 million. About 25 percent of that total was for health insurance and benefits. This figure covers 24 full-time and four part-time employees, making the average yearly compensation for a paid credit union worker $57,000.

By definition, every person with a credit union account is a shareholder, and many of its members are volunteers at the organization, serving on various supervisory committees. L.E.S.P.F.C.U. currently has 8,179 members and three branches.

When asked what L.E.S.P.F.C.U. hopes to achieve in the upcoming negotiations, Del Rio stated that it has the building’s financial interests at heart, but believes fixing the building is a shared responsibility. The credit union is proposing rent increases on the residential tenants as well as L.E.S.P.F.C.U., but rejects tenants’ demands that the credit union pay the full cost of helping the building. Another proposed solution is to negotiate with city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development for a lower property tax rate.

However, Macken argued, “The H.D.F.C.’s financial problems are solely due to the artificially low rent that the C.U. engineered for itself 20 years ago. The residents are all rent-stabilized and rent-controlled, while the L.E.S.P.F.C.U. is by now quite a large federal credit union.”

According to its C.E.O., Linda Levy, the credit union currently pays a monthly rent of $3,479. But Macken says the market rate for the 5,000-square-foot space should be $15,000.

The 1,000 square feet of this space that was previously sublet to the M.H.A. is now being used by L.E.S.P.F.C.U. According to its board chairperson Del Rio, the credit union has offered to split revenue with the H.D.F.C. from subletting the space. However, this process is on hold until later this year.

“It’s hard to find a tenant,” Del Rio explained. “It has to be a very known quantity, because it has to share space with the credit union. There are security issues,” she noted.

In addition, Del Rio said that the credit union offered to issue a loan to the 37 Avenue B board in order to fix a broken boiler.

While both sides acknowledge the complexity of their quandary, they are united in their wish to unravel it.

“We are now purely focused on resolving the financial issues in the building and moving on,” Macken declared.

However, Macken was adamant that if the negotiations fail to end in a successful agreement, the aggrieved tenants will not hesitate to “hit the streets again” with more protests.

Both parties are eager to resolve this dispute amicably by restoring the building’s economic security. It remains to be seen whether L.E.S.P.F.C.U. will forgo the significant savings of its 1996 lease agreement and pay a rent closer to the market rate.