By Julie Shapiro

I.S. 89 Principal Ellen Foote said when she found out that her school received an A this year from the Department of Education, she and her staff nearly rolled on the floor laughing.

“It’s about as meaningless as a D,” Foote said, referring to the grade the Battery Park City middle school received last year.

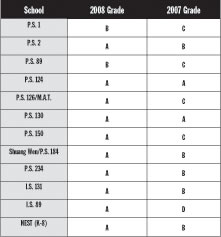

I.S. 89 was not the only school to show a dramatic leap in the city’s second annual set of report cards — 10 of 12 Downtown schools received an A, up from only two last year. All Downtown schools either improved their grade or maintained an A this year.

The D.O.E. report cards bluntly label schools A through F, based mostly on students’ test score improvement. Principals and parents raised questions about the grades last year after well-regarded schools received D’s and F’s while struggling but improving schools received A’s.

I.S. 89 received the D just weeks after being the only middle school in the city awarded a federal No Child Left Behind Blue Ribbon. Foote felt strongly that her school was not failing, so she made no more changes in the past year than she usually does. And then, this week, along came the A.

“A school doesn’t go from a Blue Ribbon award to a D and then back up to an A if you’re using valid measures of a school’s performance,” Foote said. “It’s just ridiculous.”

Sixty percent of each school’s grade is based on student progress on standardized tests, while 25 percent comes from student achievement and the remaining 15 percent comes from the school’s environment, as determined by surveys and attendance. Mayor Bloomberg and Schools Chancellor Joel Klein announced the grades Tuesday at a Bedford-Stuyvesant school that went from an F to an A. Klein plans to raise the bar next year, making it more difficult for schools to get A’s.

Lower Manhattan’s schools posted a very different set of grades this year compared to last year, when Downtown saw almost as many C’s and D’s as A’s and B’s. This year both P.S. 150 and P.S. 126/Manhattan Academy of Technology jumped from a C to an A, and five schools went from a B to an A.

Maggie Siena, principal of P.S. 150 in Tribeca, said she did not put too much stock in the improvement either.

“I’m really grateful we got an A, and I’m proud of the school and the work we’ve done,” Siena said, “but I have a lot of questions about the validity of the scores.”

Siena, like Foote, said she works every year to improve the school, but she did not do anything specific to raise the school’s grade.

The schools had very little time to make improvements, Siena said, since principals found out about last year’s scores in the fall, only four months before students took the first standardized tests that counted toward this year’s scores.

“Can a school make that significant of a change in four months?” Siena said. “It’s very difficult for me to see in practice how that happens.”

Siena said it wasn’t easy to brush off last year’s C.

“It was a hard C to live with,” she said. “It’s hard to look at something that blunt very thoughtfully.”

Foote, who has led I.S. 89 since it opened 10 years ago, called the D grade “a public relations nightmare.” She spent much of the last year trying to figure out why the D.O.E. gave her school a D, and she also had to fill out reports for the D.O.E. explaining how she would improve the school. She said she simply outlined the same goals and action plans that the school has used successfully for many years.

Having the Blue Ribbon under her belt helped Foote stay confident in the quality of the school, but she knows several principals who left after their schools received low grades, even though the schools had good reputations. Eighteen schools that received a D or an F have new principals this year, according to the D.O.E.

Foote said she and other principals who saw large jumps in their grades this year felt less a sense of accomplishment and more a sense of relief.

Last year’s grades often reversed the state’s opinion of schools, Foote said. She knew of one District 2 middle school that got a B last year but was on the state’s list of schools that need improvement. Under No Child Left Behind, many students in that school transferred to I.S. 89, a Blue Ribbon school. That meant the students transferred from a B school to a D school. This year, both schools received an A.

“How do you reconcile those discrepancies?” Foote said. “How do parents make sense of that? It just is all over the place — it’s such a disservice to schools and to parents…. It’s so simplistic at best and confusing and probably invalid at the worst, at a very high cost in terms of money, resources and morale.”

The Department of Education did not return a call for comment.

In a press release announcing the report card gains, Chancellor Klein said the grades “are giving parents and the public clearer information than they’ve ever had before about the strengths of their schools. They have also become a tool schools use to pinpoint the specific areas where they need to improve.”

Siena, from P.S. 150, thinks the D.O.E. should stop assigning letter grades to schools.

“It doesn’t give us very useful information,” she said. “It’s hard to not have a knee-jerk reaction to grades.”

Siena’s feelings about grades extend to her classrooms, where P.S. 150 students do not receive letter grades for their work.

“I don’t think it’s a useful learning tool,” Siena said.

Julie@DowntownExpress.com