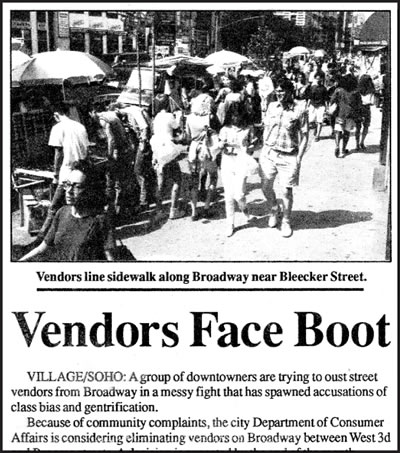

Art vendors take the heat, then and now

Last week, in an article entitled “The Rules: New limitations on art vending in city parks,” Albert Amateau described new regulations limiting the number of art vendors in city parks and the swift resistance of Robert Lederman, president of A.R.T.I.S.T., a group representing street artists. In particular, Amateau recorded Lederman’s judicial history of opposition to similar regulations, including “one that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, that stopped a previous attempt to restrict selling art and written material in the parks on the grounds that the restrictions violate the First Amendment.” But the history of vendor struggles in the Downtown area precedes even that landmark 2001 decision, as a Downtown Express article from 20 years ago, “Vendors Face Boot,” recorded.

That article, written by Jere Hester, described tensions between peddlers and Downtowners “trying to oust street vendors from Broadway in a messy fight that has spawned accusations of class bias and gentrification.” At that time, the City Department of Consumer Affairs had just begun to consider eliminating vendors from a strip of Broadway between West 3rd and Broome Streets in response to copious complaints from residents and business owners. Those pushing the regulations alleged the crowd of vendors made walking along the street “a pedestrian’s nightmare.” Some, like Soho resident Sean Sweeney, suggested the plethora of vendors were forcing him to “‘think about moving’” after living in the area for 20 years.

This concern for overcrowding is reflected today in the assertions of contemporary proponents of vendor restrictions. Amateau reported that Parks and Recreation Department head Adrian Benepe believes regulations are “needed to relieve congestion and ensure public enjoyment of the parks where those vendors currently set up without restriction.” But then, as now, vendors argued adamantly that congestion was not the issue. Hester reported that a lawyer representing the 1990 group of vendors asserted “‘this has much to do with class,’” suggesting residents were interested in relieving their expensive neighborhood from poorer workers. The article also noted the ethnic diversity of the vendors, describing the “broken English” of the imperiled peddlers. One vendor suggested that residents were really turned off by the peddlers’ racial identity, charging, “They want to make this the suburbs. This is definitely an issue of class and race.”

Although the debate has shifted from vendors on sidewalks to those working along park pathways, street artists oppose the new rules with the same vehemence as their predecessors. Last week, in an article accompanying Amateau’s coverage called “The Reaction: How vendors feel,” the Downtown Express reported the extreme frustration felt by Battery Park vendors who will soon be severely limited. “‘I will have to quit the thing I’ve been doing for nearly 20 years,” said Vlad Tixon, a painter. “‘The park authorities complain that vendors are blocking the path in this park, and there are people stumbling over vendors’ stuff. But I’ve never seen anything like that. That’s not the truth’”

And according to the 1990 article, vendors on Broadway also contemplated legal action with “a class-action lawsuit” and a petition signed by more than 2,000 supporters. But Lederman has actually engaged NYC courts once again to protect what he sees as the First Amendment rights of his peers working in City parks, and feels confident in the precedent of his earlier case. But until his suit can be decided, vendors remain uncertain of their professional futures. Their predecessors from the 1990s can sympathize with their struggles; 20 years ago, they suffered the same pains. As Hester reported then, one Guatemalan peddler feared for his livelihood and family in the face of possible regulations. “‘I need food, I need dress,’” he told Hester. “I have my children at home.” Certainly, today’s vendors feel much the same way.

— compiled by

Joseph Rearick