BY JERRY TALLMER

Museum reveals the real Man Ray, through March 14

Gotcha.

No, it’s not a New York Post gloating headline, it’s what this city’s Jewish Museum, if museums could talk, would be saying to Man Ray and, through March 14, to all the rest of us, in two different ways. But of course museums do talk, through everything they put on their walls, or under glass on tabletops, or on don’t-touch pedestals, or via explanatory wall plaques, or walk-along-with-you headphone guidance. What the Jewish Museum is saying to one and all who absorb its voluminous, inspiring, energetically curated exhibit, “Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention,” is “Gotcha! Maybe you now see how great an artist was this incredibly multifaceted American expatriate who was never taken quite as seriously as he should have been, then or since.” And what that museum up on chic Fifth Avenue at 92nd Street is saying to the late Man Ray himself is “Gotcha! You were a Jew after all and all along — an up-from-the- Brooklyn-ghetto New York kid whose Russian-immigrant parents were a tailor and his seamstress wife — no matter how much you didn’t want that to be and preferred to ignore the whole subject.” Until, that is, the age of 50, when Adolf Hitler gave you no choice but to scram from your beloved Paris to the hollowing hills of Hollywood.

And yet, and yet. At least three of the more than 180 works that now fill the ground floor of what had once been the Warburg family mansion betray direct — and, if you like, Surreal — connection to the immigrant tailor-and-seamstress Brooklyn household in which the boy who was to become Man Ray grew up. The first and most striking evidence is the 1920 grouped suspension of a couple of dozen ordinary wooden hangers — prime tools of the garment industry — under the sarcastic double-entendre title “Obstruction.” This was some ten years before Marcel Duchamp dubbed one of Alexander Calder’s constructions a “mobile.” The museum has cleverly lit Man Ray’s assemblage to project a shadow forest on the nearest wall. Part and parcel, on the floor beneath the hangers, is a battered old suitcase signifying, one assumes, a restless son’s successful getaway. The second and visually most disagreeable background clue, recapitulated several times over the years and variously titled “The Riddle” or “The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse” (1920), consists of a mysterious bulky object wrapped in an old army blanket or black canvas. The mysterious (and obviously invisible) object, known only to its appropriator, is a sewing machine of unknown vintage. The third and most famous of these three genetic betrayals is of course “The Gift” — the simple flatiron that, shortly after his arrival in Paris in 1921, Man Ray rushed to a hardware store to buy, along with a handful of teethlike tacks to fix to its base, as his wittty entry to the big Dada group show he’d just heard about. There also figures, in more than one of his paintings and photographs, of a dressmaker’s dummy like mama used to use.

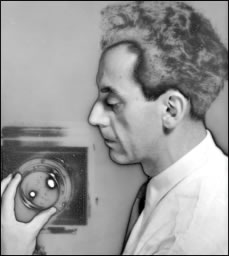

Man Ray (1890-1976) always considered himself first and foremost a painter, though his paintings are not, to me, the most interesting products of his prodigious output. I mean everybody was doing it, wielding a paintbrush, but nobody who ever lived except Man Ray was, as the Jewish Museum proves before our eyes, also a writer, a poet, a printer, a printmaker, an editor, a publisher, a sculptor, a photographer, an aerographer, a collage-ist, an assemblage-ist, a found-objects artist, a filmmaker, and two or three other things I forget. There was also, as one might expect, a rather full portfolio of life with women — from one mistress, the famed artists’ model Kiki of Montparnasse, whose flawless backside he immortalized in “Le Violon d’Ingres” (1924), to Lee Miller, the ice-cold and ambitious American beauty whom — when she walked out on him — he immortalized in a different way, cutting her eye out of a photograph he’d taken and pasting it on the ticktock arm of a metronome. This 1923 “Indestructible Object,” as he titled it, now lost except in reproduction, is on the front cover of the excellent $50, 240-page book that is the catalogue of the show. The back cover is a self-portrait as if staring at us tight-lipped through a curtain, or a prison, of raindrops. Like many others over the years, I knew his work as a photographer — fascinating, unusual portraits of Hemingway (so young and tender!), James Joyce, Sinclair Lewis, Gertrude Stein, Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, and, believe it or not, Marcel Proust on his deathbed — before I knew anything at all about the rest of Man Ray. He was born in Philadelphia, August 27, 1890. The family moved to New York when he was 7. His name then was Emmanuel Radnitzky — “Manny” to friends and around the house. Came time, he shortened Manny to Man, and the beginning and end of Radnitszy made Ray. Throughout his works there appears the motif of a hand, the French for which is “main,” which rhymes with “man.” In New York there was an abortive Dada effort at the close of World War I. But Man Ray, now living and working in a Greenwich Village studio on 8th Street, was discouraged. “All New York is Dada and will not tolerate a rival,” he wrote to Tristan Tzara in Paris, and soon afterward followed his letter there with his own self. He was running, running — in, as exhibit curator Mason Klein rather delicately puts it, his “need to escape the insularity of his ethnicity.” There, in Paris, Man Ray could simply let the whole subject of his “ethnicity” die, disappear, poof! — like that. Toward the end of the exhibit there’s a fascinating 7-minutes of film by Mel Stuart, extracted from a 1997 American Masters documentary on PBS, in which an aged Man Ray talks about his life and times. He wears heavy horn-rimmed eyeglasses and a beret cocked over one eye. “In sixty years I did a lot of things,” he says — and he sure did. Then he shuffles off down the block, an old Jew like any other…and no other. “ALIAS MAN RAY: THE ART OF REINVENTION” can be seen through March 14, at The Jewish Museum (The 1109 Fifth Avenue at 92nd St.). Museum hours are Saturday, Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday, 11 a.m. to 5:45 p.m.; Thursday, 11 a.m. to 8 p.m.; and Friday, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.; Admission is $12 for adults, $10 for seniors, $7.50 for students, free for children under 12 and Jewish Museum members. Admission is free on Saturdays. For information, visit www.thejewishmuseum.org or call 212-423-3200.