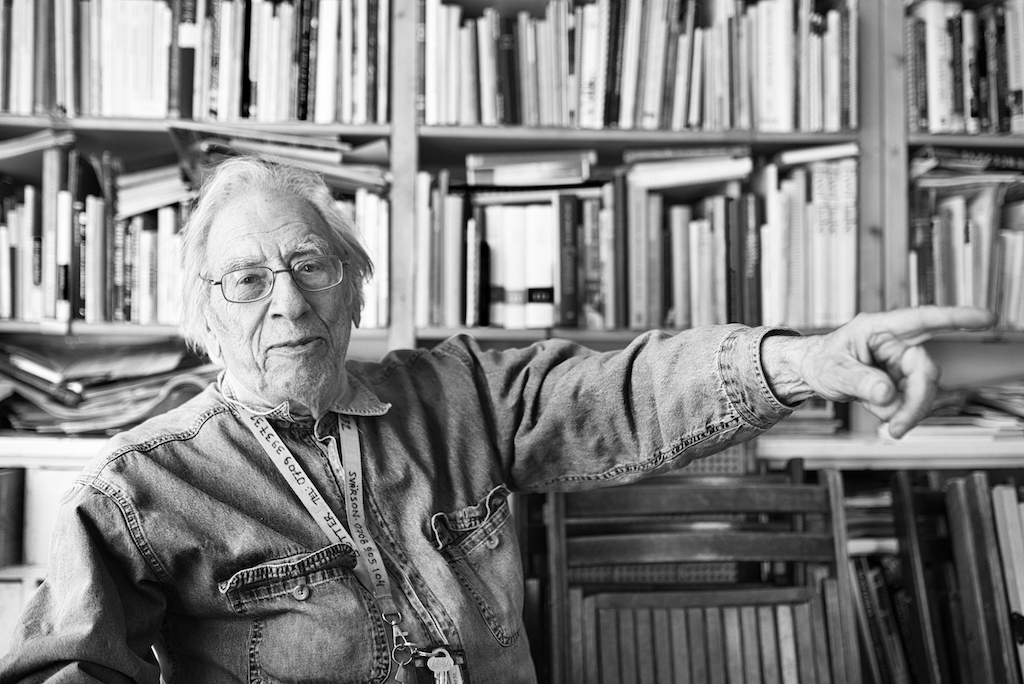

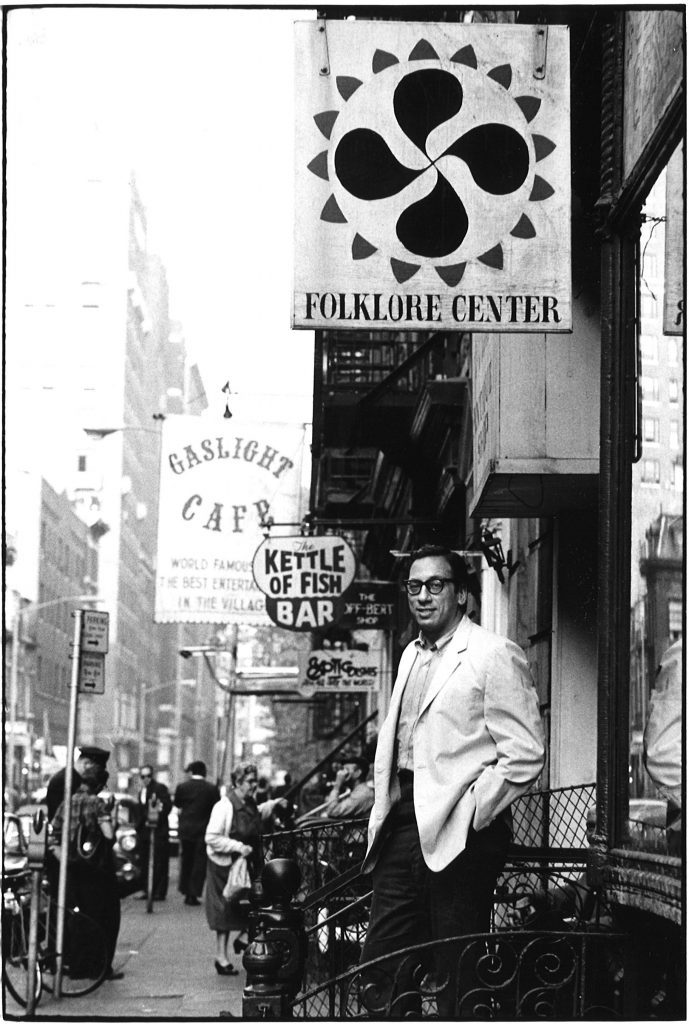

BY GABE HERMAN | Izzy Young, who was at the center of the Village folk scene, running one of its key hubs, the Folklore Center, died on Feb. 4 at age 90 in his home in Stockholm, Sweden.

Young ran the Folklore Center from 1959 to 1973. It was first at 110 MacDougal St., between Bleecker and W. Third Sts. In 1965, he moved it to 321 Sixth Ave., next to what is now the IFC movie theater.

The shop sold folk music items, like magazines, records and instruments. But it was also a meeting place where people talked and gossiped about the folk scene, and where musicians might try out songs and hope to get noticed.

Izzy Young also put on concerts, including Bob Dylan’s first in New York, in 1961. Dylan was a regular at the Folklore Center. But Young wasn’t impressed at first, he said in Martin Scorsese’s Dylan documentary, “No Direction Home.”

“He didn’t look too interesting to me, he didn’t look wild. He looked like an ordinary kid,” Young said.

When Dylan asked to play him some of his songs, Young brushed him off.

“I said, ‘Can you come tomorrow? Get out of here,’” Young recalled.

Dylan insisted and sang for Young, who then kicked him out. But over time, Young would point Dylan out to others in the shop and tell them he was writing good songs.

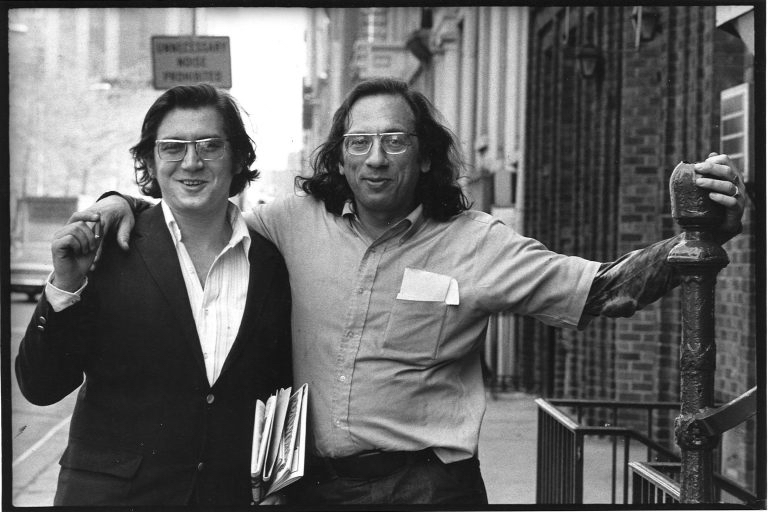

Matt Umanov, who ran a guitar shop at 273 Bleecker St. for decades until recently closing it, and now does guitar repairs by appointment there, was a longtime friend of Young. Umanov even repaired guitars in Young’s Sixth Ave. location, which was on the second floor, for a year in 1967.

“He had unbelievable energy, a real character,” Umanov said.

In the late ’60s, Young spent $5 to get ordained as a minster, and he officiated Umanov’s wedding in the Folklore Center.

“He was an outgoing character and opinionated, and let you know,” said Umanov. “He was always standing up for the little guy.”

Mark Sebastian, a musician who grew up in the Village in the ’60s and co-wrote “Summer in the City,” wrote on Facebook that Young was “the heart and embodiment of Greenwich Village.”

“It’s where we went to play guitars our family might not be able to afford,” Sebastian wrote, “and read reprints from Sing Out! and gauge from older players there just how good we’d have to get before anyone took us seriously.”

In terms of Young’s influence, Sebastian wrote, referring to two major record labels, “It was known Izzy could put in a good word for you at Vanguard or Folkways if he thought you were becoming important.”

Young was born in 1928 on the Lower East Side and grew up in the Bronx, the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland, according to The New York Times.

He moved to Sweden in 1973, where he opened the Folklore Centrum, which he ran until recently.

His daughter Philomene Grandin said her father had a childlike wonder about the world.

“He could be incredibly happy for a cup of coffee, a kiss on his cheek or someone playing a tune,” she wrote by e-mail to The Villager. “He would often cry at concerts because he thought that the ambience and the performance was so beautiful.”

But he could also be surly, she said, with “a habit of yelling at people when they entered his store. He would blame the visitors for not coming more often or for disturbing him. But it would nearly always finish up with kisses and hugs.”

She said that Young had little money and people would often bring him gifts and food.

“In some ways he was like a Buddha: happy for everything he got and surviving on gifts,” she said.

There were high moments from his name recognition, said Grandin, including free concert tickets for them to see artists like Dylan, Patti Smith and Joan Baez. And people often sought out the shop in Sweden to see Young, the man with a huge impact on the Village folk scene.

“Izzy and I would always shake our heads and laugh: ‘Oh no, not another Dylan freak,’” recalled Grandin. “I used to tell Izzy that he should take a dollar for every picture people took of him (he needed the money!).”

She and Young went to the Nobel Banquet when Dylan received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016.

“I am so happy for that night,” Grandin said. “I think that night represents a lot of the life I had with Izzy. One day poor and without a dime, and the next day we could be shining at the Nobel Banquet.”

Grandin said that just hours before Young died, there were musicians by his bed playing and singing. “Dad had his eyes closed but he was still holding the beat with his feet,” she said. “A wonderful moment.”

Izzy Young wrote a column about the folk scene for Sing Out! magazine. And when some locals and the authorities decided to crack down on the folk-music gatherings in Washington Square Park, he was a leader of the 1961 protests against the ban on the musical jams. Young led a rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at one of the rallies, which were ultimately successful in keeping folk music in the park.

(For a video of the Beatnik Riot, also known as the Folk Riot — in which Izzy Young tells the police, “It’s our God-given right to sing” — click here.)

Young is survived by daughter Philomene Grandin and son Thilo Egenberger, along with three grandchildren.

Grandin said she and her father would always spend hours in Washington Square Park, listening to live music, when visiting New York in later years.

“We used to joke that there should be a bench in the park with a little sign, with Izzy’s name and a couple of words about the riot he started,” she said. “I still think it would be a great idea and dad would love seeing it from the sky — maybe sitting down beside us, listening to some great tunes, stomping the rhythm with his feet.”