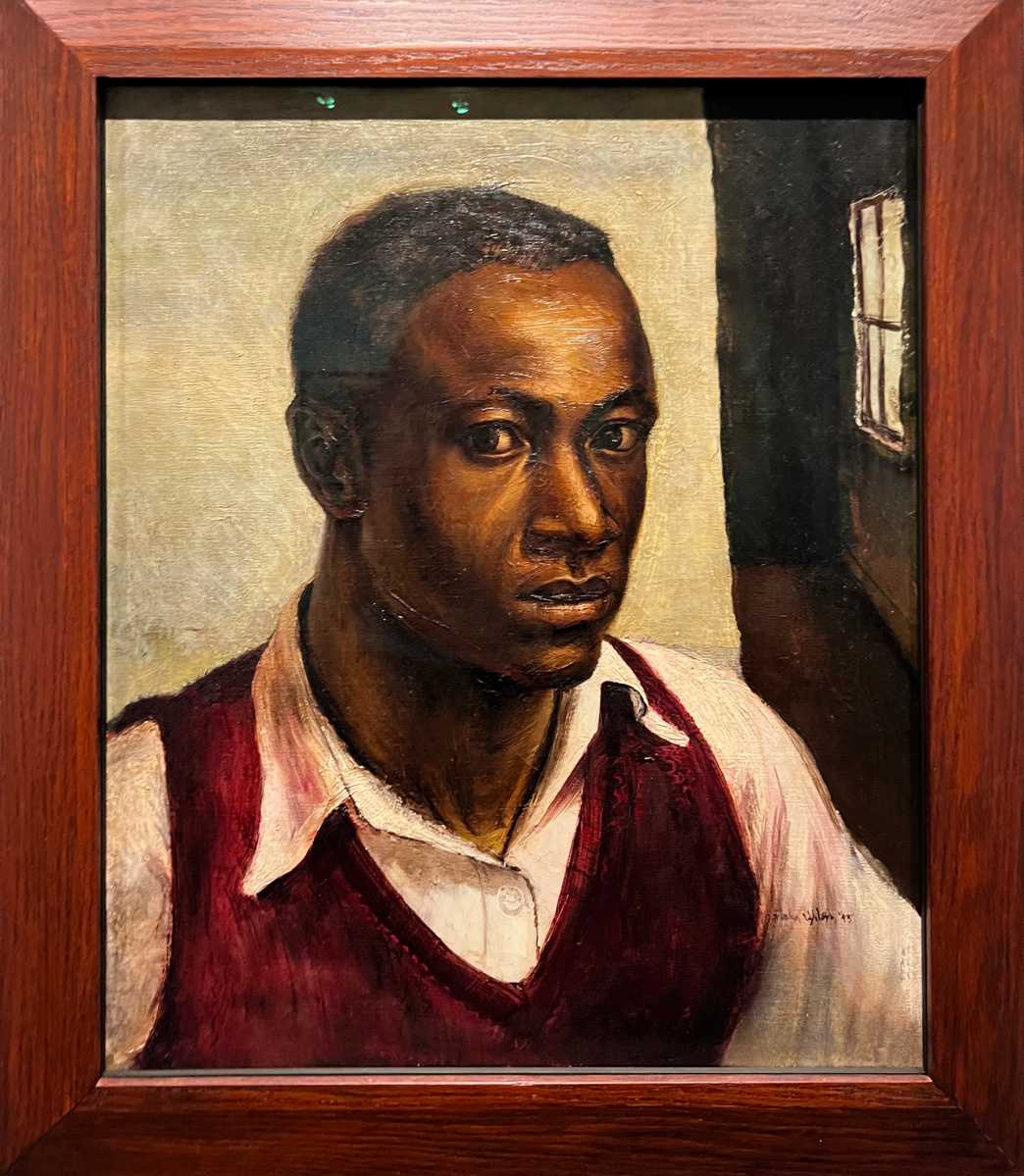

John Wilson’s name first appeared to me as an apparition — my father’s name, my beloved father, who stood as a defiant beam of light against the suffocating stereotypes America imposed upon Blackness. To see the same name inscribed upon canvases, prints, and bronzes was to recognize the continuation of that defiance—an inheritance of fire.

Wilson’s art, forged across decades of upheaval, did not merely document history; it bent history into form, forcing the viewer to confront truths too terrifying to remain invisible.

Wilson came of age in a century unraveling itself. Born in 1922 in Roxbury outside Boston, his youth was steeped in both the grotesque spectacle of American racism and the broader catastrophe of a world at war. By the time he was sketching in the 1930s and 1940s, Nazi Germany was showing America its own reflection: state-sanctioned violence, racialized extermination, the eradication of “undesirables.”

Wilson understood, as few did, that the machinery of hatred is never foreign. It is homegrown, imported and exported, tailored for the times. He picked up charcoal not as a student’s tool, but as a weapon—his black strokes cutting through centuries of erasure.

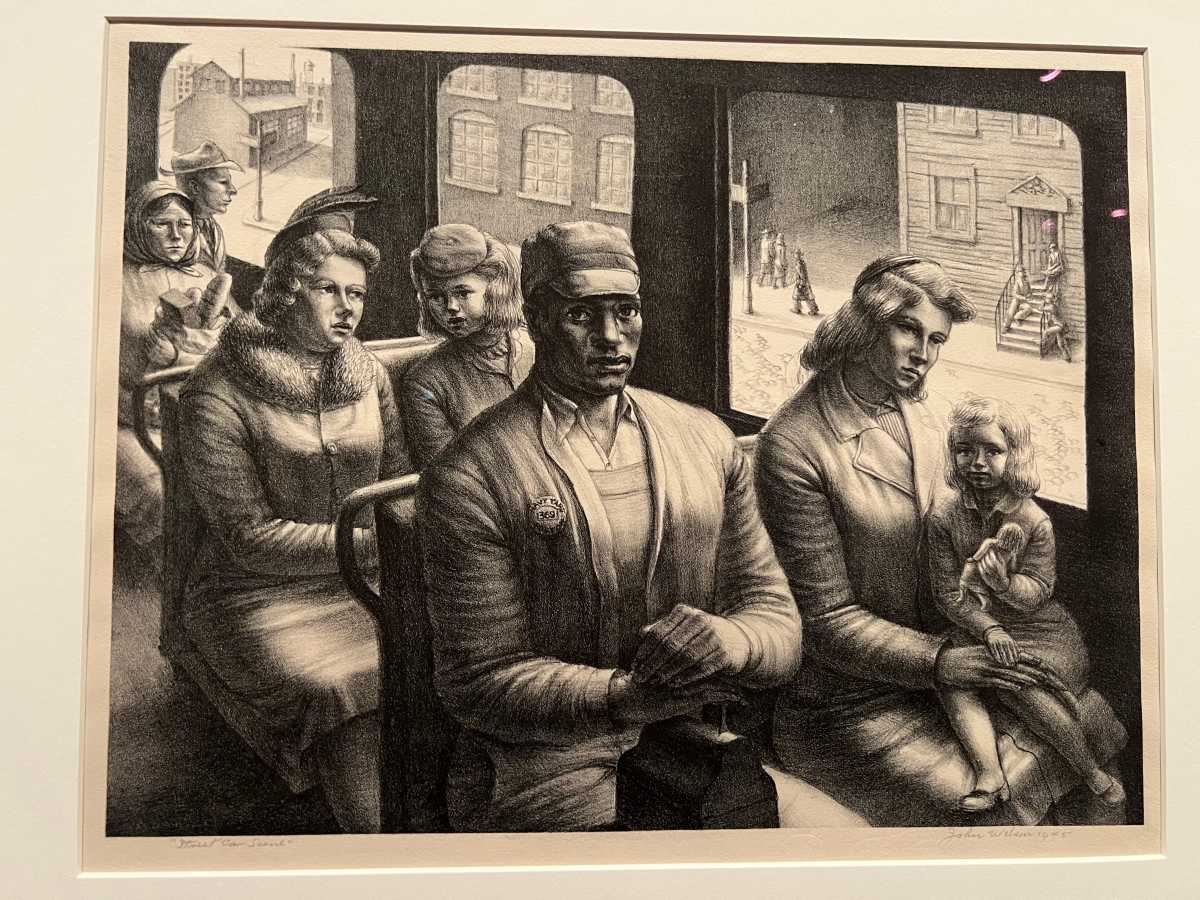

Then came Mexico, where the muralists cracked him open. Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco modeled an art that belonged not to gilded salons but to the walls of factories and schools—an art of revolution, of bloodied workers and gods with calloused hands. Fernand Léger’s modernist muscularity taught Wilson to see the figure not just as flesh but as structure: engineered, monumental. Yet where Rivera and Léger looked outward to the masses, Wilson turned inward, to the intimate violence of American racism.

It was in this crucible that Wilson conceived The Incident (1948–49), his magnum opus of horror and revelation. A charcoal and gouache drawing, it depicts a lynching—not the spectacle of the dangling body, but the scream, the mother’s scream, face contorted, arm raised in futile defense against the mob. Wilson rendered the very moment of annihilation, that split second when humanity is eclipsed by hatred.

Unlike the grotesque postcards of lynchings circulated in America as trophies, Wilson gave us the unbearable intimacy of grief. The composition pulls the viewer into complicity; you cannot look away, for the scream reverberates across centuries. It is Picasso’s Guernica transposed onto American soil, distilled into the ferocity of one woman’s cry. Beauty and terror collapse into one, proving that only art, in its paradoxical genius, can translate atrocity into truth.

One could say that to look at Wilson is to understand the essential function of art in the evolution of the human condition. His figures carry the raw defiance of Goya’s Disasters of War and the spiritual gravitas of Rembrandt’s light—but with a force even more startling, because Wilson’s brilliance was never meant to be centered in the American narrative. It had to fight its way there, each work an act of both survival and supremacy.

To say he fought across mediums would be quite an understatement. Copper etching—an art of almost masochistic difficulty—yielded to his relentless hand, every incision as precise as Albrecht Dürer’s. His lithographs, dense with velvety blacks, stand in authority alongside Käthe Kollwitz, translating anguish into lines so heavy they feel chiseled rather than drawn. His murals and sculptures—Eternal Presence, the Martin Luther King Jr. head in the Capitol Rotunda—loom as monuments, not just to leaders, but to the audacity of representing Black greatness at a scale meant for gods and presidents.

Yet the genius of Wilson is not only in the work, but in the necessity of it. He knew that without representation, without the stubborn insertion of Black humanity into the canon, history itself would remain fraudulent. His art was not a plea; it was a declaration. America could not call itself a civilization while refusing to look at the scream, the lynching, the quiet dignity of a Black father at his kitchen table. Wilson demanded we see it all.

What remains most astonishing is not only the breadth of his oeuvre, but the silence that surrounded it. How many knew of The Incident? How many were allowed to? That Wilson’s art was ever kept peripheral is itself an indictment, proof of how systemic racism consigns even the greatest to secrecy. Yet like Goya, like Dürer, like Picasso, his vision cannot be suppressed forever. Wilson’s art is history’s rebellion against forgetting.

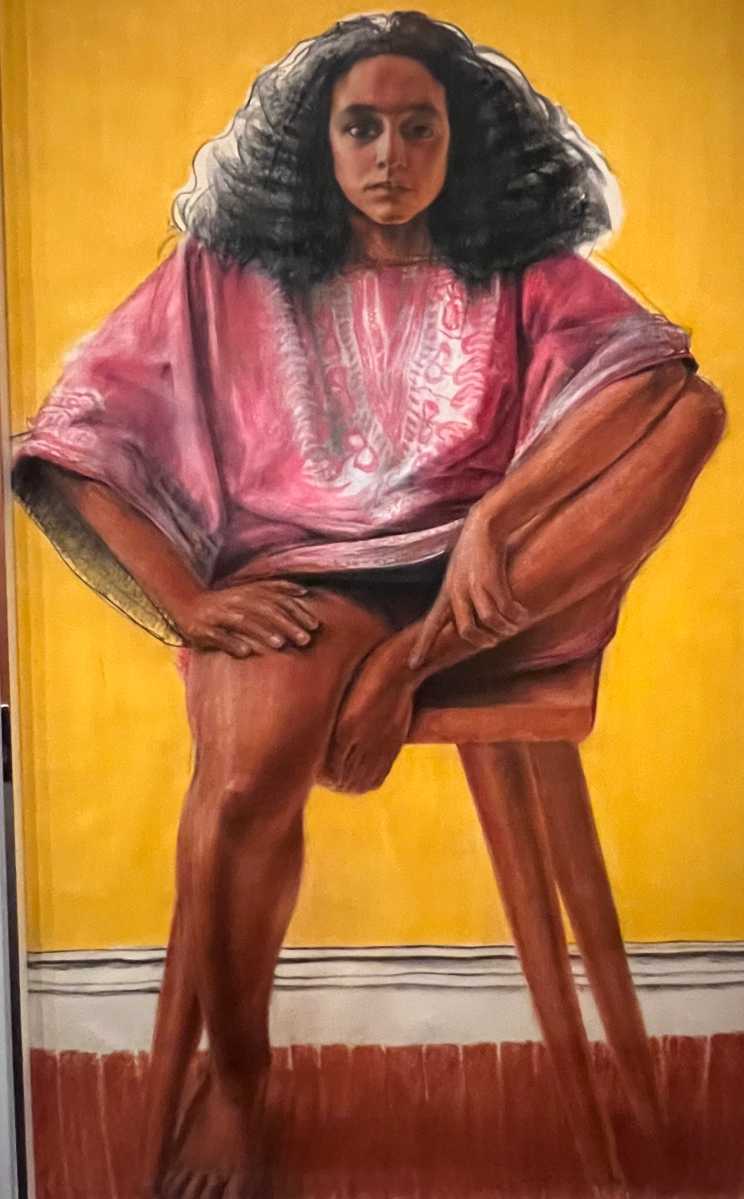

Today, as his retrospective, Witnessing Humanity, fills the galleries of The Met, it feels less like an exhibition and more like an unveiling. Over a hundred works—drawings, etchings, bronzes, murals, children’s book illustrations—declare their rightful place in the cathedral of art history. To step into these rooms is to be confronted with what America denied itself for so long: the recognition that John Wilson did not merely chronicle Black life. He transfigured it into the architecture of human truth.

This exhibition runs through Feb. 8, 2026, at The Met Fifth Avenue. Go. Bear witness. Allow John Wilson to leave you breathless.