The notion of nearly 50,000 alleged felons roaming the streets of New York City after failing to appear for a scheduled court appearance is, to say the least, troubling.

It means 50,000 people — according to the latest figures from the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice — who were arrested for serious crimes, then released on bail or on their own recognizance, who just didn’t show up for their court dates. And yet this is the universe we live in.

To be sure, many of these evasions are not deliberate. Some nonappearances may result from work or childcare commitments, transportation challenges or simply disorganization. Nonetheless some percentage of these defendants will commit new crimes. The problem is that there’s no easy way to determine whether the absence is inadvertent or a deliberate effort to elude judicial reckoning with the intention to engage in additional criminal conduct until a rearrest occurs.

Most of those remaining warrants are for failure to appear, not for the newly indicted and not yet arrested or probation violations. A study by the Data Collaborative for Justice at John Jay College found failure-to-appear rates of about 20% for nonviolent felonies and 13% for violent felonies, meaning thousands of defendants charged with serious crimes don’t show up.

As violent crime rates in New York City have plummeted since the historic highs of the early 1990s, so too has the number of felony warrants outstanding. Better court notification systems and reforms that slow automatic warrant issuance have also helped to reduce the warrant backlog.

But the story behind those warrants, and what they represent, is far more complex than a simple backlog. These aren’t just pieces of paper. They are the justice system’s promise to victims, witnesses, and the public that accountability matters.

Recent reforms and behavioral interventions like text reminders have reduced failure-to-appear rates. The city has invested tens of millions of dollars on pretrial services to defendants to assure their returning to the court without the need for bail.

Despite tabloid headlines about crimes committed by individuals released without bail, recent research tells a different story. According to Data Collaborative, felony rearrests have actually declined since New York’s bail reform laws took effect in 2020. In New York City, felony rearrests dropped by 6.8%, and violent felony rearrests fell by 5%, a trend that challenges the narrative that bail reform has undermined public safety.

But while the rearrest rates are lower, they are not zero. And regardless of whether released with or without bail, given the sheer volume of the criminal justice system, even a small percentage can mean thousands of individuals will commit additional crimes while awaiting trial. About 100 defendants a month on pre-trial release will be rearrested within a year for a violent felony. Every case represents at least one victim. That risk is real-and it’s why enforcement strategies still matter even as both crime and rearrests decline.

When someone charged with a felony fails to appear in court, the consequences ripple far beyond the courtroom. First, the defendant escapes accountability for serious charges. Second, victims and witnesses are left without closure, sometimes feeling threatened or intimidated by the lack of resolution. And third, every outstanding warrant represents a risk, however small: if that person commits a new crime, it’s a failure that could have been prevented.

This is why felony warrants, especially those issued for failure to appear, are not simply administrative inconvenience. They are a critical measure of whether the justice system is functioning as intended, and they represent a strategic opportunity to intervene before further harm occurs.

CompStat, the New York Police Department’s data-driven accountability system launched in 1994, revolutionized policing by making commanders answer for crime trends every week. Warrants became part of that culture. While shootings and robberies dominate the charts, felony warrants — especially those tied to violent crimes — are reviewed as indicators of unresolved threats.

Commanders are expected to prioritize high-risk fugitives, and the warrant squads work closely with precinct detectives to locate and arrest them. The logic is simple: apprehending someone with a pending violent felony charge isn’t just closing a case — it’s crime prevention.

This shift turned warrants from a passive backlog into an active enforcement priority. Felony warrants became a strategic tool, embedded in the city’s crime-control playbook.

But the strategy is only as good as the resources dedicated to deploying it. Because crime trends are favorable, there have been personnel attrition in the NYPD. That includes the detective bureau, in which the warrant squad is housed, which has declined from a peak 7,000 to under 5,000.

The subset of failure to appear warrants is particularly important as enforcement can be targeted without triggering some of the same racial equity issues that prompted bail reform in the first place. The criteria of a missed court date is objective. Arrests can be made on sight and don’t require additional investigation.

The question isn’t whether warrants matter. The question is how to balance enforcement with fairness, ensuring that the system pursues those who pose the greatest risk while using smart strategies to reduce unnecessary failure to appear warrants.

New York City’s crime story is often told through homicide rates and CompStat charts. But behind those numbers is another metric that speaks to the integrity of the justice system: felony warrants. They are more than paperwork — they are promises that justice will be done. And keeping those promises is essential to both safety and trust. Every effort should be made to reduce the number of people entering the criminal justice system. But for those involved with it, there should be a concentrated effort on those who deliberately fail to return to court.

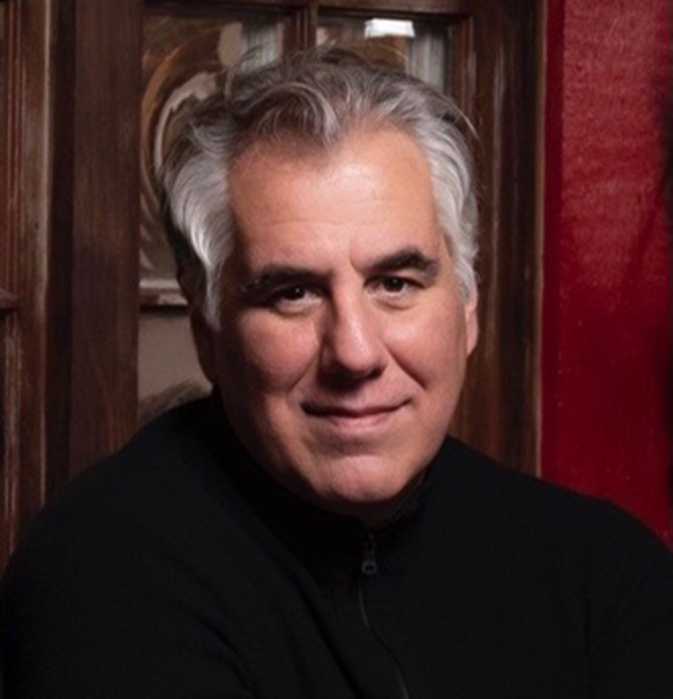

Ken Fisher is a former New York City Council Member and an attorney at Cozen O’Connor. His views are his own.