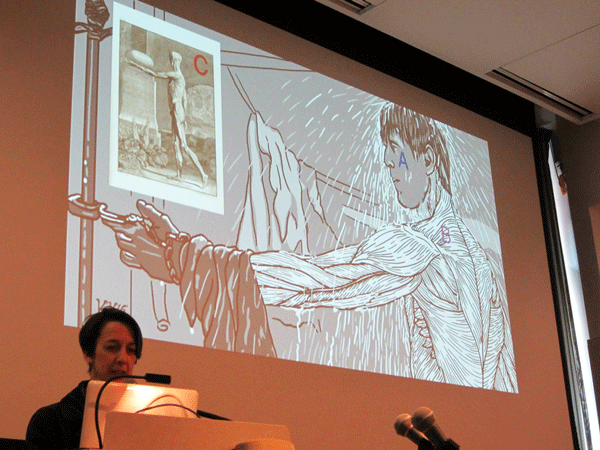

No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to pose! Kriolta Welt’s bone dry observations accompanied her “Pictorial Anatomy of 007.”

BY SCOTT STIFFLER | In 1967’s “Trout Fishing in America,” the genre-splicing counterculture author Richard Brautigan based “The Kool-Aid Wino” — one of the book’s many self-contained entries — on a destitute childhood friend who stretched his lone nickel package of the powdery substance far beyond its suggested two-quart yield, transforming it (sans essential ingredient sugar) into a gallon’s worth of day-long drinking.

“He created his own Kool-Aid reality,” the story goes, “and was able to illuminate himself by it.”

Although driven by economic necessity rather than artistic vision, the character’s knack for repurposing his source material kept coming back to me throughout April 26 & 27’s RE/Mixed Media Festival — whose concerts, installations, workshops, exhibits and lectures (held at The New School and La MaMa’s Culturehub) addressed “remix culture” on a multitude of theoretical and practical levels.

WHO OWNS THE BEAT THAT’S BEEN TURNED AROUND?

When DJs of the 1970s began to craft longer, dance-friendly club versions of disco songs by adding material not in the original recording, remixing was born. While the term is relatively new, the practice is as ancient as the second iteration of the first expression of the human condition. Whether you call it remix, mashup, hybrid, cross-pollination or adaptation, the act of creative appropriation, festival organizers note, “has been the de-facto methodology of art making for centuries.”

But if we’re all copycats, does the debt to our predecessors include a royalty payment? To what extent can anything shaped from the collective unconscious be claimed as a fresh take worthy of “intellectual property” protection? Those are questions the festival’s been asking since its 2010 debut — with the answer becoming more nuanced and elusive as 20th century copyright law is left in the dust by rapidly advancing (and increasingly accessible) technology.

Festival Director Tom Tenney, in a conversation with this paper two days after RE/Mixed IV closed, noted a shift in tone from past editions. With 48 hours of hindsight, Tenney’s already making adjustments based on the realization that remix culture “is a misnomer. It should be ‘remix cultures.’ ” With an increasing amount of international guest presenters and audiences comes a desire to broaden the conversation beyond remixing’s strictly domestic implications.

“Back in 2010,” recalls Tenney, “we were focused primarily on copyright issues — and that still does loom over everything. But not everybody who participates is necessarily a copyright activist, and that’s okay. Remix is coming to mean different things to different people. That’s good, because it’s not just a response to corporate and copyright control. It’s a tool to express yourself, using appropriative techniques.”

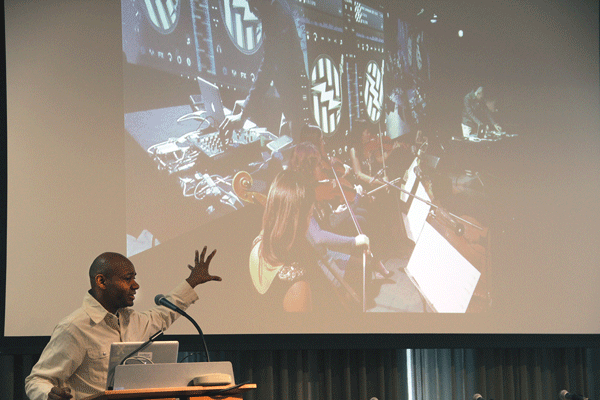

The iconic DJ Spooky traced the app icon’s rectangular frame back to the record cover sleeve.

BEEN THERE, USED THAT

“Remix owes a debt to people from postcolonial societies,” asserted Patrick Rosal, who had no problem acknowledging the shoulders he stood on. In fact, that’s largely what he came for. Immediately following the festival’s keynote address, “Breakbeat Poetics & the Digital Realm” had the Rutgers-based poet, essayist, DJ and academic paying tribute to DJ Kool Herc. The Jamaican-born innovator, Rosal noted, laid the groundwork for everything from rapping to the DJ’s cut (multiple copies of a record, aligned to the same section, for use as a sort of callback chorus).

Rosal likened cutting to “a boxer’s jab” — the base line connector to all other techniques. For a chronicle of how Kool Herc’s Bronx beat-juggling begat everything from turntabling to rapping and sampling, Rosal cited Jeff Chang’s 2005 tome “Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation” as required reading that will given you an education without feeling like an assignment.

Peppering the lecture with his own poetic raps, Rosal also spoke of the human body as “the first machine of the remix.” For a vivid illustration, he time tripped us back to the Jersey City Boys Club, circa 1986. Locked in combat with a rival crew, one of his b-boys went beyond the obligatory display of poppers and windmills, to score a decisive win by executing “the slickest version of that back-crackin’ move [The Suicide] that I’d ever seen.” Later, the dancer confessed that his game-over display of brilliance was the product of improvisation, not intent (his shoe flew off, and he worked it into the act).

It was lesson learned for Rosal, who to this day keeps a sharp eye out for how “the art of the accident” can be used an instrument to play “the truth told slanted.”

Excerpts from a work in progress illustrated that. In response to a politically motivated massacre that took place while on a 2009 Fulbright Fellowship to the Philippines, Rosal printed out a list of the victims. As heard from the other room, he was “seized by the sounds of the printer, printing out the names of the dead.” He recorded the printer, chopping its raw audio into single wave forms that served as percussive and bass sounds over which Filipino artists recited numbers that both individualized the victims and called attention to the shocking scope of the event. Another project in the works will layer a recording of bees from the Cloisters and scanner sounds over young men of color interviewing victims of police violence.

Although DJ Herc was a frequent touchstone, Rosal traced his own remix aesthetic all the way back to dear old mom and dad. “My mother constantly used things in a way they weren’t intended to be used,” he noted, recalling how she produced a handful of cooked rice when he ran out of glue, which allowed his Arizona flag classroom project to get back on track. Just as successful, but the stuff of more painful memories, was his father’s discovery that a bright orange Matchbox track could be used to “beat us in the behind.” Giving due respect to this artful use of a found object, Rosal admitted that, b-boy dance floor injuries notwithstanding, it was his best example of how “remix can be painful.”

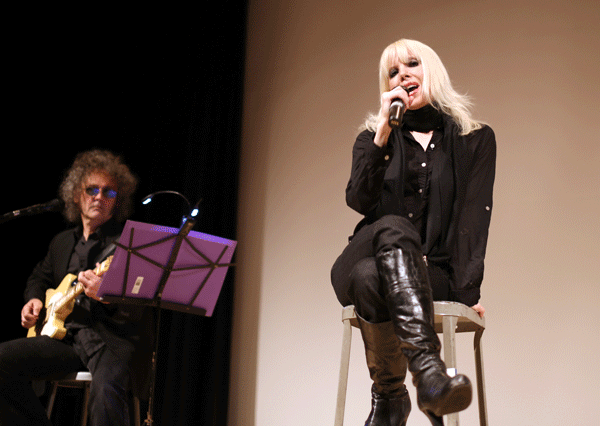

The joke’s on her, and sometimes you: Tammy Faye Starlite, as Nico, sings like angel and gives the devil his due during between-song patter.

FUNNY THINGS HAPPENED IN THE FORUM

Electronic beats gave way to comedic ones, when Rosal’s 11am lecture was followed by a rare daylight “Carousel” display. Curated and hosted by R. Sikoryak, the monthly traveling slide show features a revolving cast of cartoonists and artists reading from their work. This particular edition was downright loopy, while drawing a straight line between the featured authors and the festival theme.

Neither the voice nor the steady hand of Sikoryak trembled with guilt, as the “Masterpiece Comics” writer/illustrator did his best uncredited Jack Mercer impression — a necessary conceit, to invoke a certain sailor man whose iconic look and voice were shamelessly cribbed to tell the story of “Popysseus” (Homer’s “Odyssey” cast with characters from “Popeye”). “I miss me sweet Penelope,” he says in the first panel, leaving the isle of Calypso to reunite with a wife who looks very much (okay, exactly) like Olive Oyl. The long-suffering Miss Oyl was voiced by the next presenter, Kriolta Welt, whose bone dry delivery accompanied illustrations from her “Pictorial Anatomy of 007” — in which familiar scenes from James Bond films were dissected, literally, to reveal the fleshy mechanics allowing the composed British superspy to make strained eye contact with a poisonous spider on his shoulder or extend his handcuffed arm (in a manner, Welt noted, eerily similar to a 19th century anatomical illustration).

Elsewhere in the festival, Tammy Faye Starlite (aka Tammy Lang) performed a truncated version of her acclaimed concert, “Nico/Chelsea Mädchen.” The gifted satirist, a longtime presence on the Downtown comedy scene (mostly in her country/gospel persona), sang a “cavalcade of non-hits” from the catalog of the late Teutonic chanteuse Nico. Supported by the deeply credible musicianship of two guitarists, Starlite’s interpretation of songs including “All Tomorrow’s Parties” and “Femme Fatale” was played largely straight. Laughs, and there were plenty of them, came from glory day tales of functioning as dysfunctional muse for the likes of Andy Warhol, Bob Dylan, David Bowie and Lou Reed. “He took this from me and reflected it upon himself,” she said of Reed, while making a weak but confident case for her intellectual ownership of “I’ll Be Your Mirror.”

Starlite as Nico was similarly dour and clueless, when attempting some ill-advised bonding. “That was a very communal experience,” she said, longing for the umbilical comfort of the stage after one number spent prowling the room while speculating on the sexual kinks of audience members. “It’s very difficult to both sing and walk at the same time,” she observed, specifying that Mick Jagger’s technique didn’t count because it was “more of a jog.” With that, she gave the audience their leave: “Only two more songs,” she said, “and you’re free to go — as free as you can be in this predetermined world.” The joke was on her. We would have stayed for more.

WHEN THE IMAGINARY (APP) BECOMES REAL

The festival’s second day began with a presentation from composer, multimedia artist, editor and author Paul D. Miller.

Known internationally as DJ Spooky, he at one point mentioned that his tag line moniker, That Subliminal Kid, was taken from the William S. Burroughs novel, “Nova Express.” It wasn’t the only time a RE/Mixed participant made reference to — and expressed reverence for — a literary figure who advanced the form with cutting and stream of consciousness techniques familiar to the DJ. Patrick Rosal, for example, gave props to Keats and Dickinson, noting, “A poet is one who ‘breaks’ into language.” For his part, Miller traced the sci-fi-tinged work of Burroughs (who called language “a virus from outer space”) to William Gibson (whose cyberspace vision of the 1980s came to fruition before century’s end).

Pointing to “The Imaginary App” exhibit that surrounded him, Miller traced the imagery used to communicate the function of an app back to the work of Alex Steinweiss — who, upon adding pictorial content to the record cover sleeve, created a visual shorthand that found its perfect fit inside the rectangle. “People reduce a song to an image,” Miller said, noting how this “frame of experience” finds similar expression in a museum painting, the record album or the familiar shape housing everything from social media logos to app icons.

Set for release in August, the book version of “The Imaginary App” gathers essays and articles by writers, artists and theoreticians — and features a group of satirical (often ridiculous) apps. Among the apps featured in the book’s exhibit form: The impossible achievement promised by “Weather Changer” is self-explanatory, while “Queerify” lets you give anything a gay upgrade, simply by tapping the screen. That’s assuming you’ve not used “Assault on Battery” — which grants some off-grid downtime to the user by “turning on the most waste-tastic combination of components on your phone,” thus providing “an excuse for ignoring friends, family, co-workers that no one can blame you for.” The imaginary app allowing one to erase a building from the skyline of a photo, Miller said, is one of several no-longer-imaginary apps.

Either through self-fulfilling prophecy on the part of the contributor or sheer coincidence springing from the zeitgeist, the line between brave new idea and globally available product dissolved before the “App” project wrapped up — causing this reporter to wonder if there was an app for synergy, which would alert you when somebody with the same idea obtained legal rights and took it to market before you did. That inquiry took its final form just after the Q&A session had concluded, but no matter: Miller referred any follow-up questions to his @djspooky Twitter account.

That minds think alike is not particularly surprising. But Miller, noting that billions from China, Africa, Brazil and elsewhere will soon be adding their online voices to the mix, wondered what the face of immersive media would look like when we’re all surfing the same 5G wave.

When network systems move with a speed comparable to the imagination, the DJ “will be all about the mobile,” Miller said. That confident assertion recalled something brought up by Lev Manovich — who, in the festival’s keynote address, boiled the remix down to our biological urge to interface. Referencing a slide of social media communications in NYC before, during and after Superstorm Sandy, he called attention to the amount of dots representing activity during the blackout. “People still take pictures,” he said. “They don’t give up.”

— For more information, visit remixnycom.