By Lincoln Anderson

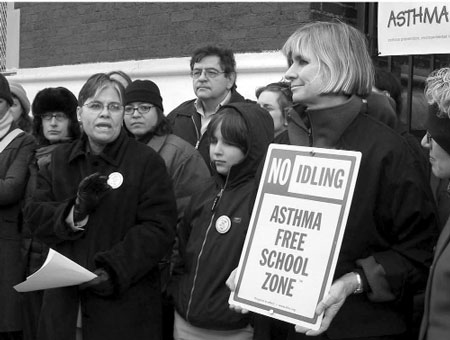

One person can make a difference. Concerned about always seeing yellow diesel school buses idling their motors in front of P.S. 61 on E. 12th St., local resident Rebecca Kalin called Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, asking him to do something about it.

“They came immediately and started taking data,” said Kalin, founding director of Asthma Free School Zone.

The upshot is that Spitzer has worked out an agreement with the metro area’s four largest yellow bus companies, under which if the buses idle for more than one minute in front of schools they risk being fined. The buses are allowed to idle their engines if the temperature inside the bus is below 50 degrees — but, if challenged, the driver must have a thermometer to prove the temperature.

Under the pilot program, also called Asthma Free School Zone, civilians can tell the drivers to turn their engines off, or challenge them if they refuse.

“The attorney general is a fan of this program because it relies on civic participation. It’s like a civilian watch,” said Kalin. “Spitzer gives us muscle, and we give him on-the-ground presence.”

Department of Sanitation workers may be used for enforcement, though details are still being worked out. Currently, police enforce the idling law — but Kalin said police have their hands full with other responsibilities.

Under the city’s current laws, parked, stopped or standing vehicles may only idle three minutes, except for emergency vehicles or vehicles loading or unloading, which may keep motors running. The state law caps idling at five minutes.

The Spitzer agreement goes into effect at the end of this month.

“Small people are far more vulnerable to pollution than big people,” said Kalin of why she focused on protecting students. “We don’t have a lot of choice about the air we breathe.”

Kalin said the money from fines will go toward planting trees — which absorb pollution — near schools.

The four bus companies concerned are Atlantic Express, Logan, Consolidated and Pioneer, which operate more than 60 percent of the yellow buses in the area. Three of the companies will retrofit their buses with pollution-trapping mufflers and some will be converted to run on low-sulfur fuel.

Kalin noted that most cities own their own school bus fleets and have tapped into federal money to upgrade their vehicles to run cleaner. New York City, however, is serviced by privately owned yellow buses.

A.F.S.Z. will also offer environmental health training to staff members of the school and parents or even to members of local gardens and senior centers. The zones will range from one block to up to four blocks, depending on where children enter and exit the particular school, where playgrounds are located and other factors. Each school’s parents association will determine the size and location of the zones and where the street signs denoting the zones will be posted, Kalin said.

Kalin noted that Dumpsters may also be targeted for violations, since often volatile chemicals and other substances that pollute the air and can cause respiratory diseases and asthma are discarded in Dumpsters. Similarly, the A.F.S.Z. school team members might also work to insure that roof repairs or high-pressure cleaning of nearby buildings — activities that can also release chemicals and airborne particles — are scheduled when children are not at school.

Following up on Spitzer’s agreement with the bus companies, Councilmember Margarita Lopez is introducing anti-idling legislation in the City Council that will apply to all vehicles, not just school buses — including cars and movie trailers — in Asthma Free School Zones and codify the A.F.S.Z. rules, in terms of their size and signage. Under Lopez’s legislation, the zones will extend 500 ft. from the schools’ property lines.