BY DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC | The patient: Mom-and-Pop stores. Symptom: High rents. The prognosis: Some on life support. Course of treatment: A town hall last week took a look at some prescriptions.

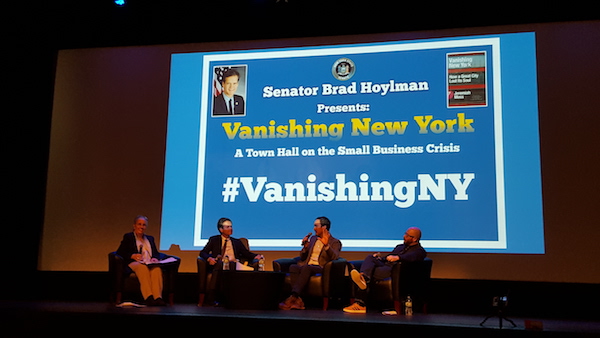

Applause greeted State Senator Brad Hoylman before he even kicked off the event — a town hall on the city’s small business crisis — at an auditorium at the Fashion Institute of Technology (227 W. 27th St., btw. Seventh & Eighth Aves.) on Thurs., Nov. 9.

“We’re here to ask a few important questions,” he told the good-sized and engaged crowd. “What has happened to our beloved mom and pops? Why does it feel like more and more of our neighborhoods stalwarts are disappearing? What can we do to save the New York we know and love?”

In May, Hoylman released a report — called “Bleaker on Bleecker: A Snapshot of High-Rent Blight in Greenwich Village and Chelsea” — that “examined the growing specter of vacant storefronts throughout Manhattan,” he said.

“In case after case, landlords pushed out local businesses, it’s perceived, in order to hold out for luxury retail or corporate chains capable of paying higher rents,” Hoylman said. “The result is a glutton of empty storefronts, chain stores, pharmacies and high-end national brands that lack local character.”

He added, “Bleecker Street is the cautionary tale of how high rents in the Village and Chelsea are pushing out longtime businesses.”

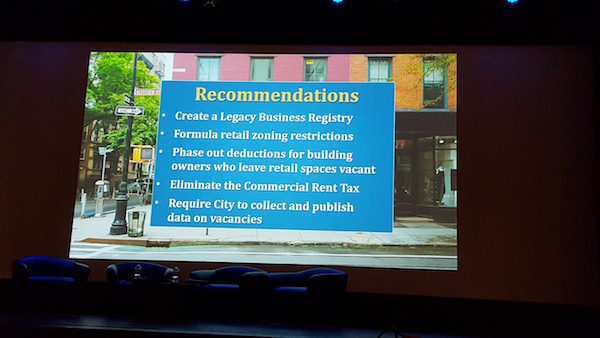

The report made some recommendations that Hoylman brought up at the town hall, which included creating a city registry of small businesses that have been in operation for at least 30 years, zoning restrictions for national chain stores, and phasing out deductions for landlords with persistent vacancies.

Another solution is eliminating the commercial rent tax, “an onerous and outdated burden,” on small businesses, he said, that applies to many commercial tenants below 96th St. and north of Murray St.

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, who spoke after Hoylman, explained that businesses that pay $250,000 or more in rent per year pay this commercial rent tax.

Councilmember Dan Garodnick sponsored a bill that those paying under $500,000 in rent do not have to pay the tax. It has yet to pass in the City Council, Brewer said.

Brewer and Councilmember Corey Johnson have sponsored legislation that would exempt grocery stores from the commercial rent tax.

“I’m afraid grocery stores in Manhattan might become endangered species, you know, like a bird or something,” she said. “But we have to have grocery stores. I’m not wanting to have FreshDirect on every single corner. I want my grocery store.”

On Mon., Nov. 13, Brewer, Erik Bottcher (Johnson’s chief of staff), and members of the National Supermarket Association had a rally in support of legislation to nix the tax for supermarkets in Manhattan.

“Affordable supermarkets are lifelines for our communities,” Johnson said in a press release, and the proposal “would give our neighborhood supermarkets a fighting chance for survival.”

“Every neighborhood needs a supermarket and access to affordable food, but even the most successful supermarkets operate with slim profit margins,” Brewer said in the release. “Ending this tax can and will make a big difference for these essential businesses.”

Rudy Fuertes, president of the National Supermarket Association, said in the release it is “no secret” that the industry is in crisis “with neighborhood grocery stores closing their doors regularly and leaving communities devoid of healthy food options.”

In Chelsea, grocery stores have been shuttering — most recently, Garden of Eden, which closed in August after two decades on W. 23rd St.

At the town hall on Thursday, Brewer said she was hopeful to pass the legislation at the same time as Garodnick’s bill, but noted, “All of this is challenging.”

Like Hoylman’s office, Brewer’s office surveyed empty storefronts, with her saying that they walked from the bottom to the top of Broadway and found 188 vacancies. “It’s outrageous,” she said.

Brewer is also proposing some kind of registry for the vacancies, and, perhaps, a penalty for property owners who keep storefronts empty for a certain amount of time.

“We don’t have a real sense of the problem because the city doesn’t collect data on empty storefronts,” Hoylman said later during a panel discussion. “They say you can’t manage what you don’t measure. We’re not measuring how deep this impact is, we feel it in our hearts and souls but the city isn’t registering in its database.”

Brewer also talked about the Small Business Jobs Survival Act, which she helped write when she was working for then Councilmember Ruth Messinger and that has been pending since 1985. Brewer also sponsored the bill when she was a councilmember.

“I cannot wait after 25 years,” she said. “We’ve got to find something that will pass and that will save the small businesses.”

After Brewer spoke, Hoylman introduced the evening’s featured speaker, Jeremiah Moss, whom he met during the campaign to save Cafe Edison in Times Square. Moss chronicles “the disappearance of longtime businesses in Manhattan and across every borough,” through his “Vanishing New York” blog, and, now, a book with the same name, Hoylman said.

“I know we’re here tonight to talk about the small business crisis in the city, which is close to my heart and we all know what it looks like,” Moss started off saying, noting the mass evictions and “overproliferation” of chain stores.

He added, “A city that is becoming homogenized. It’s looking like everywhere else and it’s becoming, in some ways, quite deadened, and we all know the reason, right?”

Moss told the audience his presentation was “really about history” and was going to focus on the “two engines that drive today’s hyper-gentrification, as I call it. And those two engines are racism and neoliberalism.”

In the late 19th, early 20th centuries, New York City went through a population shift with immigrants coming mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe, African Americans fleeing Jim Crow South, and bohemians arriving from across America along with early LGBTQ people, Moss said.

“And this combination created what I really think of as the soul of New York. … It was colorful and queer and creative, pushing for social justice, the labor movement. It was not perfect but it was a more progressive place,” he said.

City elites and the federal government pushed back, according to Moss, leading to deindustrializing as well as rezoning of the city. By the 1930s, the practice of redlining — red lines marked off areas of high risk — denied African Americans loans for homes and businesses, he said, and so “African Americans were also unable to access and accumulate wealth and these neighborhoods started to decline.”

People of color were placed in these grim housing projects or pushed into already overcrowded parts of town, like Harlem or Bedford-Stuyvesant, and disinvestment and decline continued, Moss said.

By the mid-1970s, the city is in crisis and this was exploited by this new economic philosophy of neoliberalism, Moss said.

“Liberal here really means to liberate the market,” he said. “The liberation of banks. It’s radical free-market capitalism. It’s a really a return to the Gilded Age of the 19th century before the progressive era.”

After describing waves of gentrification, Moss draws a line to the administration of Mike Bloomberg, saying that he “was the ultimate expression of the neoliberal philosophy in approach to governing the city.”

During the Bloomberg administration, 25,000 buildings were demolished, 40,000 buildings went up — Moss said a lot looked “like glass boxes that all look the same” — and 40 percent of the city was rezoned, he said.

“It may seem like I’ve gone way out there to talk about the small business crisis… but it really is all connected,” Moss said.

After his presentation, Moss, Brewer, Hoylman and Tim Wu, an author, professor and contributing writer to the New York Times, discussed additional solutions, and fielded questions from the audience. Moss said he would really like to bring back commercial rent control, noting that the city had such a mechanism in place after World War II for almost 20 years.

Wu, who has written about “high-rent blight” in the West Village, said he was going to end an optimistic note.

“I believe we can save this city,” he said. “I believe a lot of people really care about this… People are talking about this right now… The city has shown a resiliency. It has saved itself before and it can save it again.”