Words spill out of Bernhardt Wichmann III in an endless, unpredictable river.

NYC abounds in chatter boxes, but Wichmann, 82, has more to say than most: Complications from a 1983 surgery to remove polyps from his vocal chords left him mute: Until earlier this month Wichmann had not spoken for 32 years.

On Aug. 7, after emerging from an MRI machine at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System in Manhattan, Wichmann reflexively mouthed “thank you,” to the technician: And the words “thank you” emerged.

Since then, “I’ve never talked so much in my life!” exclaimed the Korean War veteran and retired architectural draftsman who lives in a tiny, lavishly collaged $300 a month room on the Upper East Side. “The three words I want to hear from someone — it hasn’t been said yet — are ‘please shut up!'” he said.

Wichmann, who has a host of medical issues ranging from prostate cancer and “an iffy heart” to weak legs and bladder problems, was receiving an MRI to diagnose a brain irregularity that is causing him to see terriers in top hats, boys on bicycles and starfish that are not there.

The gradient magnets in the MRI are “what caused me to talk” after nerves in his throat were mistakenly severed, he believes.

More likely is that the muscles and ligaments of his vocal chords were injured in the original surgery, but changed shape with age to finally permit the vocal folds to flutter properly and produce speech, said Dr. Babak Givi, director of head and neck surgery at Manhattan VA Medical Center and NYU Langone Medical Center.

“As we grow older, the muscles and structure of our larynx changes; our voices get higher and the muscles get smaller,” Givi explained. Another possibility is that the original injury was compounded by poor post-op speaking habits (“dysphonia”) and Wichmann emerged somehow relaxed from the 45-minute MRI and able to recruit the correct muscles to talk, Givi continued.

Such a spontaneous recovery of speech is “extremely rare,” Givi said, noting that such surgeries are now much more precise and less likely to leave patients voiceless or with speaking difficulties.

Wichmann had been offered another surgery to insert a prosthesis in his trachea that would allow him to speak but eschewed the procedure, preferring to scribble down his thoughts and needs on paper and in notebooks he carried everywhere. “I have glasses full of pens and pencils I don’t need any more,” he said with a laugh, adding, “I could never get things done as quickly without talking.”

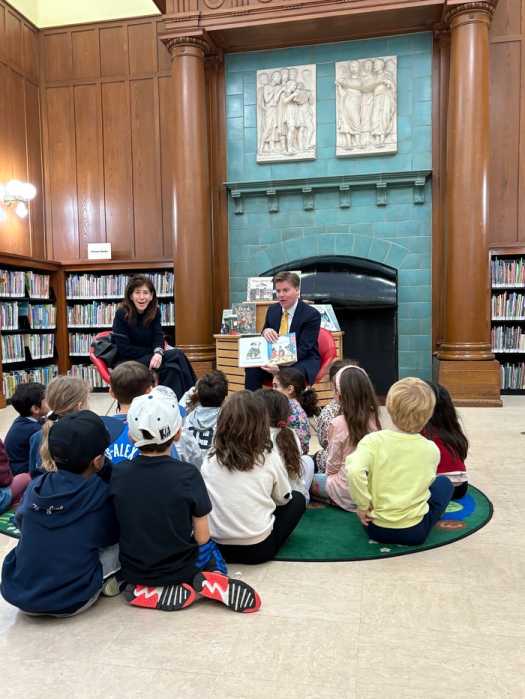

Indeed. Wichmann was on a tear at the Manhattan branch of the VA hospital last Wednesday, getting a CT scan and other diagnostic tests, picking up his costly cancer meds and meeting with social workers to obtain a Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption, transportation reimbursements and other services. “I’m down to $2!” said Wichmann, who survives on VA and Social Security benefits.

“I met him five minutes ago and the amount of content we’ve discussed so far would have taken 30 minutes,” had Wichmann had to respond in writing, said Richard McKee, a hospital social worker.

Wichmann is a familiar face in his neighborhood, where neighbors and two nearby doormen look out for him and make phone calls on his behalf in a way that recalls the closely knitted NYC communities of old. “We’re trying to get him a telephone, now that he’s talking,” said Juan Arias, 51, one of the doormen. But Wichmann — who mistook a cellphone for a nurse’s “call” button — isn’t much for telephones or technology. “I don’t have a computer. No cellphones or none of that: I know how to write!” Wichmann said. He paused. “But I’m happy not to have to write anymore,” he admitted.

It is fitting that Wichmann’s first words were “thank you” as he abounds in gratitude. “I’ve had such nice friends who have looked after me: I’ve had a nice life so far,” he said. But, he concedes, in response to a question about relationships, he is pretty much alone. “I’ve had a homosexual leaning, but I never fell in love. I thought it was so silly,” he explained.

Wichmann allows that he grew up in an era where being gay was more fraught than it is now. “Now I’m 82 and I don’t have any care for it: It’s too much of a mess,” he said of romantic love.

In the “words that were never spoken” category, Wichmann had a friend named James, a waiter, and “I would write, write, write” every time they were together. But James, Wichmann recounted, died of stomach cancer around 2003. “I would so like to say, ‘James! How are you?’ He would have fallen off his chair!” Wichmann said.

The mysterious return of Wichmann’s voice evokes the story “Awakenings” by the British neurologist Oliver Sacks, in which a patient emerged from a catatonic state only to eventually revert to his previous condition. Is Wichmann afraid of losing his voice again?

“Not really. I’m worried about losing my eyesight!” he said.