By Clayton Patterson

Edited by Margaret Santangelo

In writing this article I have but one goal: to set the record straight about Puerto Rican Lower East Side-based artist Angel Ortiz. Keith Haring expert, Jeffery Deitch, director of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), refuses to recognize Angel Ortiz’s place in art history. Known as “Little Angel,” and “LA II,” Ortiz was an important contributor to the final oeuvre for which Keith Haring would ultimately be known and celebrated. However, Angel Ortiz has not yet earned recognition or acceptance as an inspiration and essential influence on the work of his critically acclaimed peer Keith Haring.

In fact, the identity of Keith Haring’s primary partner — Angel Ortiz — who collaborated with him create to the look Haring is now so well known for, does not appear in many Haring/Ortiz collaborations, nor in exhibitions, in historical literature or in gallery catalogues.

Angel Ortiz should be recognized as one of the most important and successful Puerto Rican artists to emerge from the Lower East Side in the 20th century. Ortiz’s work, without attribution, is privately held, as well as featured in museum collections. His images appear in books and are licensed to products, again without his permission or knowledge. In other words, Ortiz has been consistently shunned by the art world. In 1982 at Keith’s and LA’s first high-profile show at Tony Shafrazi, the gallery cataloged it as a Keith Haring solo exhibition, although LA II had a number of pieces in the exhibition, again without credit.

After Haring’s untimely death, the Whitney Museum of American Art curated a solo Keith Haring exhibition. Angel Ortiz went on the museum tour reviewing the installation. The group was standing in front of a Haring/LA II collaboration that was erroneously attributed solely to Keith Haring. LA asked, “Who is LA II?” The uneducated (or uninformed) museum guide answered: “A black artist who is dead.” However, Ortiz contradicted him, declaring to the group, “I am that person.” But, the Whitney tour guide did not let Ortiz continue; instead, he was promptly escorted out of museum.

Keith Haring began his career as a graphic artist. After the Haring/Ortiz partnership was fully established, there was a marked expansion in Haring’s imagination, as well as his visual vocabulary, that can be attributed to this collaboration. Ortiz’s role in Haring’s artistic development is clearly delineated by the unique and original look of their co-produced works. Their partnership was complementary artistically: the sense of scale, the spacing, the consistency of the line, the patterns; as well as practically: the fast work pace and the extended hours. Haring and Ortiz both worked the same way and the collaboration seemed to be a perfect fit. Soon after the Haring/Ortiz partnership flourished, so did the possibilities: gallery representation, trips abroad for openings, showcases at prestigious museums.

After Haring made a concerted effort to meet LA II in the early 1980’s, Haring and Ortiz were constant creative partners for six years out of Haring’s decade-long career. In fact, the two continued, according to LA II, to collaborate right up until Haring stopped working in 1989. Their collaboration produced hundreds of esteemed, sought-after and valuable pieces, which were exhibited in galleries from New York to Tokyo to Europe. This partnership was no different from that of Braque and Picasso during the genesis of Cubism, except Braque was given his proper credit. Moreover, it is important to note that Keith’s own writings always included LA II in his history. It is Deitch and the Whitney, among other art historians, critics and businesspeople, who have omitted attribution or overlooked the role of Angel Ortiz in the history and the development of this very valuable body of work known only to art lovers as that of Keith Haring.

There are two authoritative, oversized, full-color art books about Keith Haring; one authored by Jeffrey Deitch, and the other by the Whitney Museum. Both books leave out attribution to numerous Haring/LA II collaborations, as well as work done solely by LA II.

Deitch prides himself on his deep connection to Keith Haring. Deitch, according to his own Web site, www.deitch.com/gallery/about.html, knew Keith Haring since 1980, and is the exclusive representative for the Keith Haring estate. Yet this highly respected “authority” on the work of Keith Haring and director of a prestigious art museum cannot tell the difference between a Keith Haring solo piece and a co-produced Haring/Ortiz? Why not?

Is Angel Ortiz, a.k.a. LA II, invisible because he is Puerto Rican? Is this rejection of Ortiz’s rightful place in art history actually a product of blatant classism and elitism? Is Angel Ortiz too “ghetto” for the uptown art world? What exactly is the reason for this blatant disregard for intellectual and historical integrity when it comes to establishing the attribution and provenance of Keith Haring’s work?

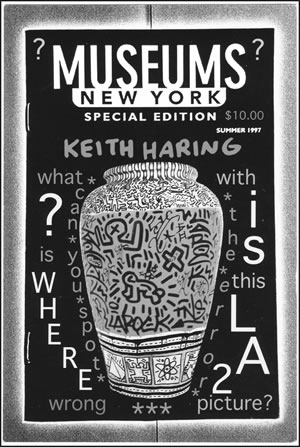

Like most talented, true artists, Ortiz’s work is easily recognizable; he has his trademark look and feel, not to mention, his prominently placed tags throughout the pieces. Any layperson (much less a seasoned art critic, such as Deitch) could recognize Ortiz’s creative input. His tags “LA II,” “TNS” and “LA ROCK” are clearly featured prominently in pieces that are, nonetheless, attributed solely to Haring.

Imagine how depressing it would be if your work was exhibited in museums and private collections, reproduced in important books, studied in classrooms, yet all the credit went to another artist. Such is the fate of Angel Ortiz. It is time that MOCA director Jeffery Deitch — a leading authority in the American art museum world — set the record straight.