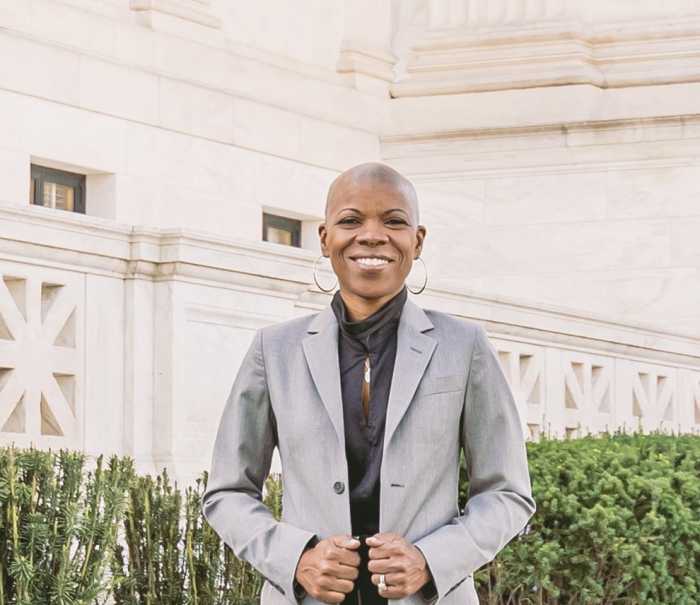

Shalliyah Garth was on her way to her job at a King Kullen on Long Island. Waiting for the LIRR at Penn Station, she saw the “something” we’re warned about every day: an unattended package.

It was a small box in a plastic bag, Garth, 27, remembers. People kept ignoring the sight. So she mentioned it to an MTA police officer standing nearby.

On Monday, Garth was one of the regular citizens lauded by the MTA for saying something, as the MTA unveiled a new version of the “see something, say something” campaign.

Get ready to hear the slogan “New Yorkers Keep New York Safe,” part of a campaign featuring city residents who reported suspicious activity to the authorities.

What do you see?

The original “see something, say something” campaign was created by the advertising firm Korey Kay & Partners in 2002, in the aftermath of 9/11. Many in the city felt vulnerable and there was a sense of agency in taking part in our own safety.

In 2010, a Times Square T-shirt vendor famously spotted a suspicious car seeping smoke. He alerted a police officer. It turned out to be a car bomb that ignited but failed to explode.

These are the stakes, and the reason that the MTA receives 20,000 to 30,000 reports a year, according to MTA spokesman Aaron Donovan.

With the rise of the Islamic State and attacks in Paris and San Bernardino, the sense of a threat here in NYC is still real.

Donovan says the MTA is updating the campaign to “keep the message fresh,” yet this is also the most significant change to the messaging since the campaign began and seems conspicuously timed at a moment when we’re discussing security threats again.

The new slogan is fairly bland and doesn’t add much to the old one. Perhaps the largest shift is the addition of a human face, a break from the faintly Orwellian imperative of constant vigilance. “See something, say something” urges a fear and condemnation of anything out of the ordinary, dangerous or not. And the phrase only vaguely explains what to do.

Garth, for example, who was able to find an MTA officer at Penn Station, says she rarely sees officers or personnel when leaving the station at a deserted end of her Crown Heights stop. Underground, she couldn’t call.

Police officers on the train make her feel safer, she says, but they’re rarely there at 3 a.m., for example.

As for the package she identified: She says she didn’t know whether it turned out to be anything serious. But people were certainly paying attention — the officer told her they were aware of the bag. Someone had already told them and it was being checked.

Say what?

Urgent slogans only underscore the difficulties inherent in keeping a subway system like New York City’s safe.

Paul Larrousse, director of the National Transit Institute at Rutgers University, says that securing open systems like the MTA network necessitates due diligence on the part of transit staff, police and riders, in addition to tools such as technological “sniffers,” or regular canine units.

Anything more direct is difficult: “Can you imagine screening for every passenger on the NYC subway? Impossible,” he says.

Neither the MTA nor the NYPD was able to immediately release the numbers of those 20,000 or so reports that ultimately reveal dangerous activity, but it’s hard to believe that the number would be high.

Even in the attempted Times Square bombing, the most cited success of “see something, say something” in NYC, the alert citizen may not have made the difference in keeping New York safe.

Taking the subway is an act of trust — of our fellow riders, but also of institutions: the MTA, oversight organizations, police and other law enforcement entities working to keep the subways secure. Good relations between law enforcement and communities can lead to tips that stop attacks; smart oversight of security work keeps that work effective.

But it’s mostly in our imaginations that we personally keep ourselves safe.

This is amExpress, the conversation starter for New Yorkers. Subscribe at amny.com/amexpress.