As New Yorkers head to the polls this week to vote early for the June 27 City Council primary elections, they’ll be able to cast a ballot for more than just one candidate.

That’s due to the city’s relatively new ranked-choice voting (RCV) system, which voters in the five boroughs overwhelmingly approved through a citywide ballot measure in 2019. The system has so far only been used in the 2021 primaries for mayor, public advocate, comptroller, borough president and City Council and a handful of special elections since the beginning of that year.

Before RCV was enacted, New York City had a plurality voting system, where voters marked down one candidate on their ballots and the contender with the most votes — but not necessarily a majority of votes — won. Proponents of RCV, such as the good government group Common Cause New York, argue it allows a more diverse array of candidates to run for office, while saving the city from having to shell-out for costly runoff elections.

Furthermore, they say the system also prevents vote splitting — where a candidate is able to win without a majority, which has mostly benefited white candidates.

Under ranked-choice, voters can rank up to five candidates — with number one being their top pick and number five their bottom choice. The candidate who captures the majority of top-ranked votes comes out on top.

Once all of the ballots are in and counted, if a candidate receives 50% of the vote in the first round, they automatically win the race. But if no contender reaches a majority of first-place ballots in round one, the contest goes to additional stages of vote tallying.

At the end of each round, the lowest vote-getter is dropped from consideration and their votes go to whomever was put second on ballots cast for them. That process continues until there are just two candidates left standing. The one with the higher number of ballots wins.

Voters can mark down five candidates, just one or however many they wish — they are not required to fill rank a specific number. But if they choose to pick the same person for all five spots, it will only count as one vote for that candidate.

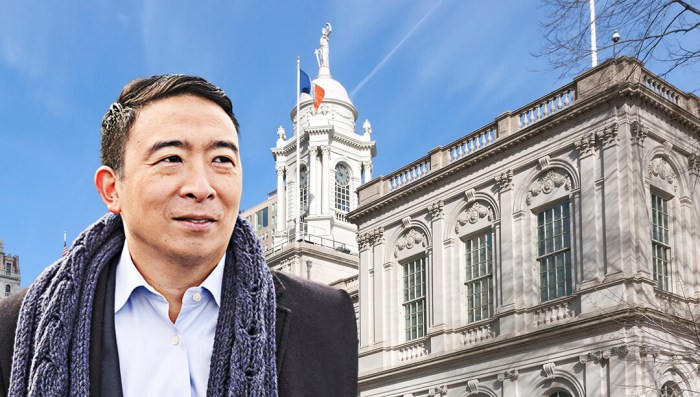

Chris Coffey, a Democratic consultant who was a co-campaign manager on Andrew Yang’s failed 2021 mayoral bid, told amNewYork Metro that there are pros and cons to the system for candidates. While the implementation of RCV did away with a system that mostly benefited white candidates, Coffey said, it eliminated the two-week period before an election where the field would naturally narrow to a couple of candidates whose qualifications would then be placed under a microscope.

“I will say, having gone through it, I get the good governance parts of it,” Coffey said. “On the flip side, at least in the mayor’s race, the primary comes really fast and in the old system, you would basically eliminate everybody but the top two. And you then had a couple of weeks to really vet number one and number two and push and prod and all those things. You don’t have that now.”

The voting system has also given rise to a new strategy where some candidates cross-endorse each other, asking their voters to rank them first and their chosen opponent second.

In the 2021 Democratic mayoral primary, Yang and Kathryn Garcia, now Governor Kathy Hochul’s director of state operations, used the team-up tactic to try and box out Mayor Eric Adams, who ultimately came out victorious. Coffey said the strategy worked in boosting Garcia to second place, ending up with 49.6% of the vote to Adams’ 50.4%, once all of the RCV rounds were finished.

“You could demonstratively see that there were voters who had been Yang voters who switched to make their second [choice] Kathryn Garcia, so it certainly benefited Kathryn,” Coffey said.

But Coffey said the RCV alliance strategy really only works in close contests.

“Ranked-choice isn’t magic, right?” Coffey said. “It’s not going to, all of a sudden, take someone who’s in ninth and put them in first. But where it works is if you’ve got a three-way race, and everyone’s within three or four points, and the third and the second [candidates] team up, you can get pretty close to knocking off the first.”

The tactic is being used by sets of candidates in two separate Democratic primaries this cycle: races for the 1st and 9th Districts in Manhattan.

In the first district, which covers much of lower Manhattan, nonprofit underwriter and founder Susan Lee has teamed up with policy expert Ursila Jung against the incumbent: Council Member Christopher Marte (D-Manhattan).

And in the Central Harlem-based Council District 9, Assembly Member Al Taylor (D-Manhattan) and Yusef Salaam of the “Exonerated Five” have also endorsed one another in hopes of one of them overcoming Assembly Member Inez Dickens (D-Manhattan) — who is the race’s frontrunner.

“Harlem is facing many challenges and we both agree that it is time for change and that we need leaders who will be on the ground every day, in the community, listening to the voices of our neighbors,” Taylor and Salaam said in a joint statement last week. “The stakes in this election are very high, which is why we are proud to cross-rank each other for City Council.”