QUEENS, N.Y. — The first thing that Kimberly Harrelson-Psarras, daughter of Mets great Bud Harrelson, remembered about her father’s 13-year playing career in New York was the fight he had with Cincinnati Reds star Pete Rose in Game 3 of the 1973 NLCS.

“I remember when he came home, I remember it like it was yesterday,” Harrelson-Psarras said. “I remember him being banged up. He didn’t really talk about it, but I remember him being very calm and somber about it but you definitely could tell he was in a scuffle.”

In a way, those moments after that game perfectly embodied Harrelson’s Mets career. He batted just .234 during his career in Queens and hit just six home runs across 1,322 games. Yet he was a solid defender, a 1971 Gold Glove Award winner at shortstop, and a two-time All-Star.

“He was kind, he was generous… There wasn’t a person he turned away,” Harrelson-Psarras said. “A scrappy player… he got out there and he did it and he put his heart and soul into every game he went into.”

He was also an integral part of the 1969 World Champions, the 1973 NL pennant winners, and later, the third-base coach of the 1986 World Series winners — the only person in franchise history to be in uniform for all three of those moments.

“When you think about the history of the Mets, Bud Harrelson is such an important part of that,” Mets owner Steve Cohen said.

“This is a person who is arguably one of the more beloved Met figures of all-time,” president of baseball operations David Stearns added. “Someone who impacted multiple generations of Met fanbases in a very impactful way.”

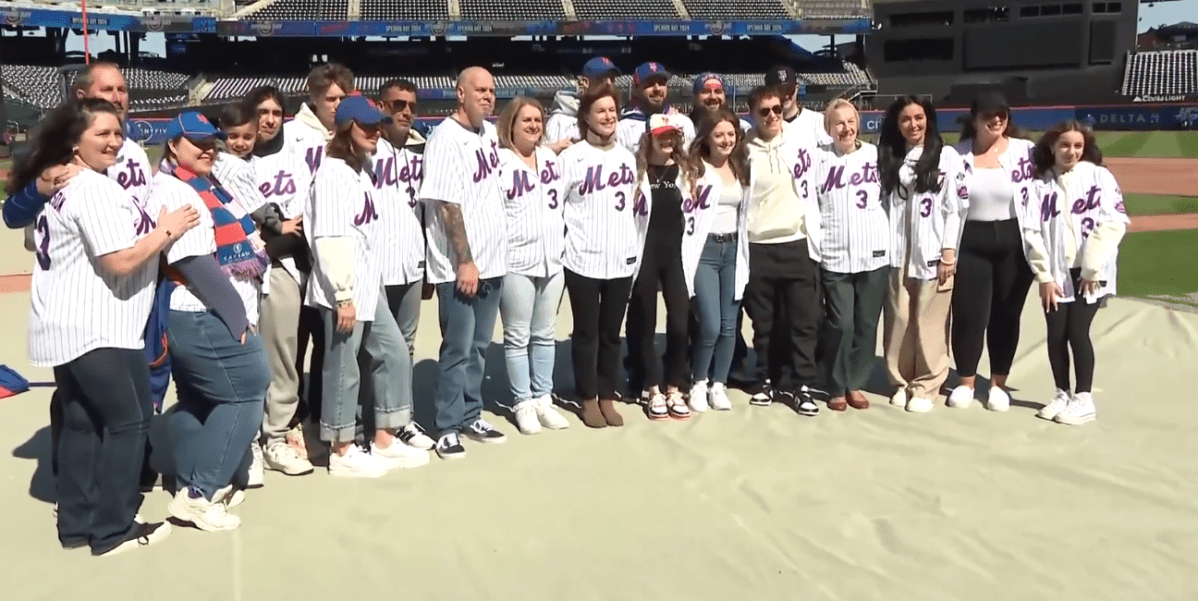

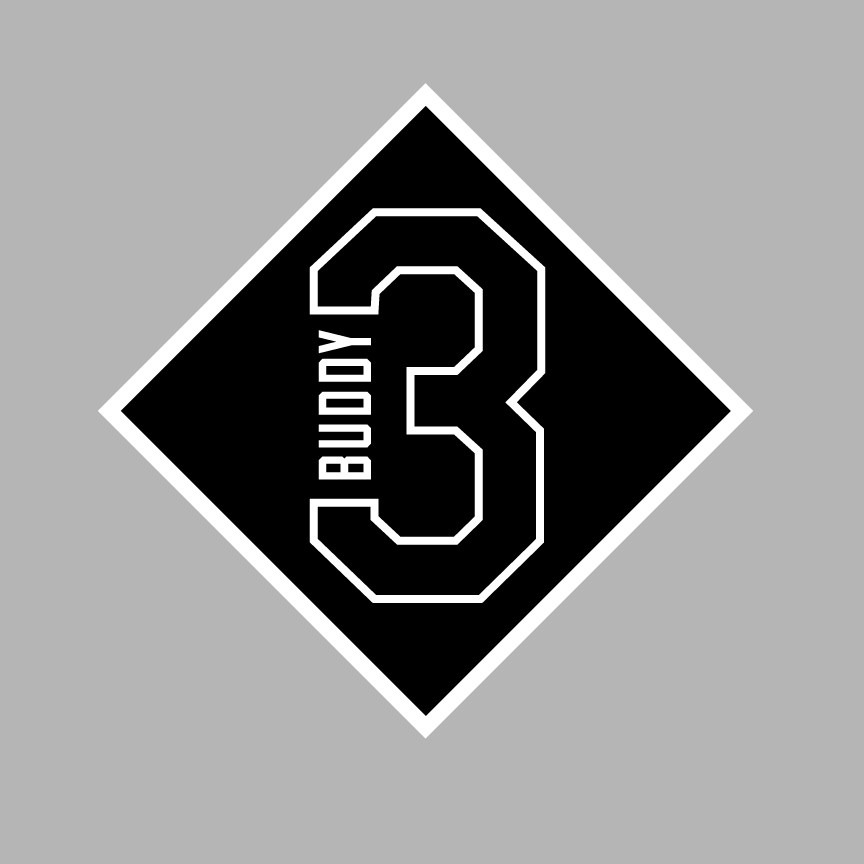

After a lengthy battle with Alzheimer’s, Harrelson passed away at the age of 79 on Jan. 11. To honor him, the Mets invited 23 members of his family, including his six grandchildren, to Opening Day on Friday to throw out ceremonial first pitches. The team also unveiled a commemorative patch to be worn on their uniform sleeves throughout the 2024 season to honor him, a tribute that Harrelson-Psarras described as “an amazing, somber moment,” when they were told of the Mets’ plans.

“It just seemed like the right thing to do,” Cohen said. “He played on the ’69 team, he played on the ’73 team, he was a coach on the ’86 team — all great moments for the team. We just felt like it was the right thing to do.”

His on-field accolades were only sweetened by the man he was off the field. Harrelson, a California native, never left the area as he settled down on Long Island and helped establish the Independent League’s Long Island Ducks, something Harrelson-Psarras admitted was one of her father’s proudest accomplishments.

Off the field and away from the ballpark was where he cemented his legacy, though, as an active father, grandfather, and member of the community with the same diligent, blue-collar attitude that made him a beloved Met.

“Family was everything for him. He loved his kids, loved his grandkids,” Harrelson-Psarras said. “There wasn’t anything he wouldn’t do for his family. The same for his fans. He signed autographs any time, he never turned away anybody.

“He wouldn’t have made [this] a big deal. He would have taken it and probably would have said that he doesn’t deserve it, but he would have taken it with pride and loved that he was honored. But he wouldn’t have made a huge deal of it.”

As for the Mets, they are no longer turning away from their history thanks to Cohen’s arrival at the start of this decade — and making deserved big deals out of those who deserve it.

“It’s meaningful for our organization,” Stearns said. “To have his family here… to be able to commemorate him with a patch throughout the season, I think it was important for us that we’re doing it.”