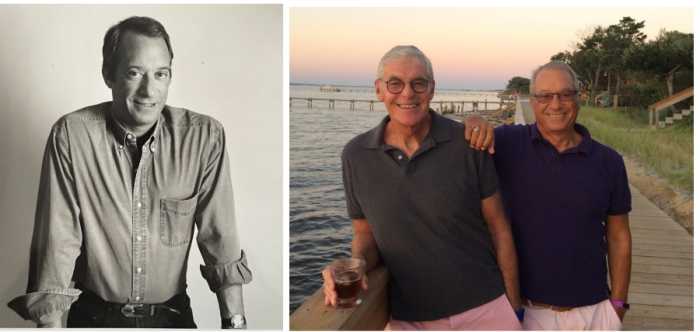

A specialty of Adam Silvera, the top administrative judge for New York City courts who started his career as a personal injury attorney, is getting cases to settlement quickly.

And that’s exactly what he argues the courts need to address its backlogs, where for example over 20 percent of some felony criminal cases take nine months on average to resolve.

Last September, Silvera became deputy chief administrative judge for the New York City courts, the fourth in command of the administration of the state court system within city limits — a role that oversees some of the most sprawling and voluminous courts in the country.

As an administrative judge, Silvera is tasked with running the day-to-day operations, supervising staff and generally “making sure that the lights are on” in the nearly two dozen courthouses around the city.

It’s a challenging role — and one with a lot at stake. While his job involves overseeing the employees and facilities of the city’s court system, Silvera described the system’s top priority as getting cases moving efficiently. When cases stall it has major repercussions for the individuals held in pretrial detention on Rikers Island or children involved in custody or neglect cases in family court.

“Family Court matters and getting the cases of incarcerated defendants on Rikers Island — whether there are pleas, whether those cases get heard, [or] get their trials. Those are the key priorities of this administration,” Silvera said.

While understaffing, leaking roofs and other facilities problems in courts around the city fall under Silvera’s purview, they extend into legislative and city authority. Facility problems? They’re up to New York City, the court building’s landlord, to address. Judicial staffing? The court system is pushing for it in the budget, but increasing the number of supreme court justices will require legislation and a constitutional amendment.

What that leaves as Silvera’s primary concern is the expediency of the courts, and he said that the court administration has equipped him with one key tool to solve this problem: Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), or as Silvera likes to refer to it, “appropriate dispute resolution.”

ADR offers ways to resolve a case without a trial — often through less formal, less expensive means like mediation or arbitration. It’s a process that offers opportunities for parties to discuss the prospect of settling outside of court.

Silvera’s early career as a personal injury attorney for 12 years before becoming a judge made him adept at finding mutually agreeable solutions that could resolve cases without a lengthy trial.

“Those are my happy moments… getting those cases to resolution is what I’m good at,” said Silvera, who continues to preside as an elected trial judge two mornings a week.

His trajectory to top New York City judge originated in his early experiences as a grassroots Democratic political leader as well as his private practice focusing on negligence, medical malpractice, labor law and civil rights litigation.

Silvera said he entered personal injury law because “it was great being able to help people.” When he became a judge he found himself using “those same skills… Just listening to people with problems, having the patience [to try] to solve their problems.”

When he was approached for the post of deputy chief administrative judge, he felt especially drawn to the approach of Chief Judge Rowan Wilson, who has outlined a mandate for all parts of the court system to adopt a problem-solving outlook toward their jobs.

He works with his direct supervisor, New York’s First Deputy Chief Administrative Judge Norman St. George, to oversee the expansion of ADR, which under Wilson went from being just arbitration to mediation, neutral evaluation, community dispute resolution and settlement conferences by the court.

The volume of cases in the city makes this approach critical, Silvera said. Manhattan’s Supreme Court civil division has 40,000 filings per year. In Kings County, there are 50,000 filings — highly specialized judges are floundering under the work.

Unlike many administrative judges, Silvera didn’t spend his entire career in the legal sphere. Growing up as a “Lower East Side kid,” he went to Queens College and became a community activist and worked as an intern in the press office of Governor Mario Cuomo before moving into a role in Cuomo’s constituent affairs unit and eventually as a staffer at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). He was a Democratic district leader in the 1990s and stayed a fixture of Manhattan political circles after he graduated from Brooklyn Law School until he was elected to New York City civil court in 2014.

Why after establishing a career in government, did he go to law school? “I had a Jewish mother,” he joked, adding on a more serious note that he and his brother both felt like they had to get an advanced degree to get to the “next level” of the American dream.

Silvera’s father was a first-generation immigrant from Tunisia and his mother second-generation from Hungary and Romania. As a result of his melting pot origins, Silvera speaks four languages fluently, and is trying to master a fifth, Arabic, to use when he visits his father’s home country. This quintessential Manhattan immigrant story contributed to his interest in public service.

“My father was a shoemaker. I grew up with humble roots,” Silvera said. “Nothing was handed to me. I was a scholarship kid when I went to Queens College.”

His political organizing and connection to Lower Manhattan was an important building block toward running for office. He spent his first two years as a judge in family court resolving disputes with families in crisis.

He recalled devastating cases that taught him why justice needed to be meted out quickly. These included a dispute involving an arranged marriage with immigrants isolated in a new country where there were signs of abuse, or presiding over an order of protection for a transgender child from the grandfather.

“We’ve got to get the custody, the visitation, the neglect, the abuse cases moving. We’ve got to get the youths in detention moving,” he said.

At the end of 2021, he was named administrative judge of the New York County supreme court’s civil term.

His legacy in his previous role as an administrative judge was “getting back in the courthouse.” He took over the job as workplaces began to return in-person after the COVID lockdown. Silvera knew that the hybrid schedule that had been adopted in some city courts was not going to fly long term.

“In a big-volume jurisdiction, we need cases to be back in person, and I was happy to lead that charge. And I met with a lot of resistance and that was okay,” he said.

Many of the challenges Silvera is contending with in his current role both surpass and predate COVID.

He conceded that courthouses in the five boroughs are in need of renovations, but it’s not within the court’s authority to repair since the city owns the court facilities and leases them to the court system.

“Every courthouse has problems in the five boroughs. And even statewide. But I mean, the problem is we’re not our landlords. So we have to work with our landlords to get it done,” Silvera said, adding “But we’re just a small peg on the larger with other needs. And other people are pulling the mayor in other directions with other infrastructure needs.”

But the most discussed challenge in the New York City’s court system is the case backlog. City Comptroller Brad Lander found that criminal cases in New York City take significantly longer to process through the court systems than any comparable jail system in the country — a problem that has gotten worse since the pandemic. Cases in family court have similar problems.

Silvera dismissed the impact of the pandemic saying that the backlog “happened before COVID. That’s been since the beginning of litigation,” and pointed to the factors that are beyond the courts’ control.

Last year the state legislature passed a law that added 12 civil court judges for New York City, including citywide positions that will be distributed across the five boroughs at the discretion of the mayor. Silvera added he heartily supports legislative efforts to expand the cap of supreme court judges, which involves a protracted process to amend the state constitution.

“We desperately need the judges. The amount of motions filed is crushing,” he said.

With these systemwide problems extending outside the court system’s direct control, Silvera said that’s where practices like ADR come in.

“That’s why ADR is so crucial and… our key to reducing the backlog,” Silvera said. “And the lawyers and the litigants and the stakeholders have been so receptive to employing ADR…Because it could take a long time, especially in family court.”