Andrew Barth Feldman is plugging in to Broadway’s quirkiest robot romance.

The “Dear Evan Hansen” alum and “No Hard Feelings” star will take on the role of Oliver in the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical “Maybe Happy Ending” for a nine-week limited engagement beginning Sept. 2. He replaces Darren Criss and stars opposite Helen J Shen, who continues in the role of Claire.

Their pairing carries added resonance: Feldman and Shen are a real-life couple who first met while studying musical theater at the University of Michigan. Not only that, Feldman served as the reader for Shen’s audition tape. But the decision has also reopened long-simmering questions about who gets to represent whom on the American stage, particularly in works rooted in Asian culture.

“Maybe Happy Ending” is not just a whimsical love story between two helperbots. It’s a rare example of a Broadway musical with Asian origins that has achieved both critical and commercial success in the U.S. The show was originally conceived and written in Korean, by Korean composer-lyricist team Will Aronson and Hue Park, and premiered in Seoul in 2016. The English-language adaptation had its U.S. premiere at the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta in 2020 and opened on Broadway in November 2024.

From the outset, the Broadway production embraced inclusive casting, with multiple principal roles portrayed by actors of Asian descent. Darren Criss, who is of Filipino heritage, originated the role of Oliver on Broadway and became the first actor of Asian descent to win the Tony Award for Lead Actor in a Musical for his performance.

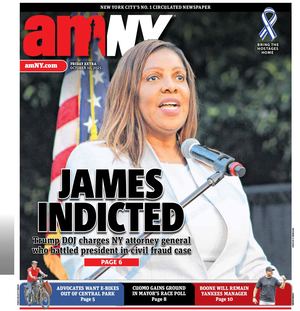

Feldman, who is white, stepping into the role following Criss has prompted criticism from some members of the Asian American theater community, who see the move as a step backward in terms of visibility, representation, and opportunity.

In the press release announcing Feldman’s casting, Aronson and Park, joined by director Michael Arden, addressed the show’s casting philosophy in broad terms. “At its core, ‘Maybe Happy Ending’ is a story about the longing for connection and the complexities of being human (and Helperbot, and Vegetable) — universal themes that transcend all backgrounds,” they said in a statement. “We’re proud to continue embracing infinite and exciting possibilities in casting, and to showcase this role as one that welcomes different interpretations and lived experiences.”

As of press time, neither Feldman nor the production team has publicly addressed the criticism directly.

Concerns over casting in Asian stories are not new. For decades, Asian American artists have pushed back against white actors being cast in Asian roles or in works rooted in Asian stories and authorship. In 1991, the casting of Welsh actor Jonathan Pryce in the role of the Engineer, a Eurasian character, in “Miss Saigon” drew widespread protests when the production transferred from London to Broadway.

Pryce’s casting also inspired David Henry Hwang’s 2007 play “Yellow Face,” which received an excellent Broadway revival last season that was recently broadcast on PBS. The play explores both the systemic marginalization of Asian American performers and the difficult questions surrounding race-conscious casting.

Among those who responded publicly to Feldman’s casting was actor Conrad Ricamora, a longtime advocate for Asian American representation in theater. Shortly after Feldman’s casting was announced, Ricamora responded publicly on Instagram: “There’s a lot of pain right now. Pain from being told—subtly and explicitly—that we don’t belong. Pain from watching history repeat itself, even as we fight for representation. Pain that I know so many other Asian American men in this industry have felt before me.”

Ricamora’s advocacy is especially notable given his own trajectory. Last season, he earned praise for playing Abraham Lincoln in Cole Escola’s surreal alt-history comedy “Oh, Mary!,” a casting choice that upended traditional expectations and was seen as a bold and affirming moment for Asian American representation onstage. That contrast helps explain why Feldman’s selection has struck a nerve.

That’s part of what makes the disappointment over Feldman’s casting so resonant. The concern is not simply about a white actor taking on the role, but about the broader pattern in which Asian performers are sidelined, even in works with Asian origins, creators, and themes.

To many Asian American theatergoers and artists, “Maybe Happy Ending” is more than a quirky musical. It stands as a milestone and a marker of how far Broadway has come, and how easily that progress can be undone.